Tell someone you’re going to Fresno and you’ll get a strange look. It’ll be the same look whether you’re in California or out, sort of a why-would-you-want-to-do-that look. That’s because Fresno is the red-headed step-child of California cities.

The fifth largest metropolitan area in the state, Fresno has no iconic landmarks, no famous residents, and few alluring tourist attractions. Yet Fresno has a claim to fame no other California city can match. It played an important role in shaping who we are as Americans. Fresno played a key role in the birth of the credit card. And the story of that birth is fascinating.

The Stigma

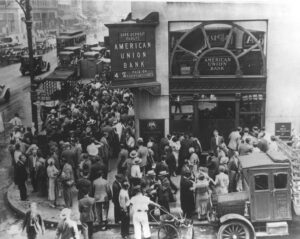

In the 1940’s American’s attitude toward dept was shaped by the experience of the Great Depression. The image is of a bank run in 1932.

Credit cards are so commonplace in modern day life it can be surprising to learn that their first appearance is actually fairly recent. Prior to the 1950’s most people paid for things with cash. Not only was consumer credit rare, most people didn’t want it. Borrowing money carried a stigma that had its roots deep in the depression. So many borrowers had been burned by the banks during that awful downturn that the idea of being indebted to them was distasteful. Institutions that offered consumer loans were considered shady, and consumers who took out short term loans were considered morally weak. But something happened in the early 1950’s to change all that.

The Allure of Prosperity

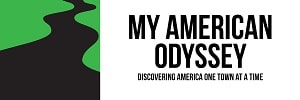

America’s post-World War II economy began to prosper, and the primary beneficiaries of that prosperity were the middle class. Incomes were on the rise and so was productivity. American factories began churning out a startling array of consumer goods: televisions, refrigerators, washing machines, power lawn mowers, and more. Consumers wanted them, and they wanted them sooner rather than later. In addition, eating out at restaurants, something considered a luxury in the 1940’s, suddenly became affordable, and the number of restaurants began to grow.

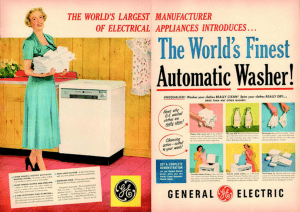

In recognition of this, Diner’s Club International was founded in 1950 and offered restaurant goers a revolutionary new way to pay, a card that could be used in lieu of cash at participating establishments. This was a charge card; no interest accrued, and users were expected to pay off their balances at the end of each month. But consumers for the first time had something other than cash in their wallets.

To feed the growing demand for consumer products, department stores got into the act by offering installment loans for high ticket items, but these pay-over-time loans, modeled on automobile loans, which had been around since the 1920’s, were for a single item. What was missing was the type of loan that had long been available to American businesses, a line of credit that would allow consumers to buy whatever they wanted within a certain limit. Enter A.P. Gianni, the son of an Italian immigrant from San Jose, California.

The Green Grocer’s Inspiration

A.P. Gianni started out as a green grocer with a simple but powerful idea. He saw potential in serving the little guy. Unlike many other businessmen, Gianni was less interested in making a killing by securing a few well-heeled clients, and he focused instead on building a customer base of mostly working class people. As a result, his green grocery flourished, and before long he parlayed his success into opening a bank founded on the same principles. Since most of his customers were first generation Italian-Americans like himself he called it The Bank of Italy.

So successful was his business model that within fourteen years The Bank of Italy was the fourth largest bank in California. Then Gianni went on a buying spree, snapping up his rivals. By the end of World War II, the Bank of Italy was the biggest bank in the world, and it had a new name. Now it was called Bank of America.

The Spread of Branches

With good reason, Gianni believed his banking model was something that ought to expand nationwide, but he had a problem. Banking laws in the United States were based on the conviction that small community banks were safer and less prone to corruption than big, remote institutions. Nationwide banks were prohibited. Gianni’s ambitions to spread his bank beyond California appeared to be thwarted, but then he realized he had another way to spread his institution, and an outsized canvas to spread it on.

In keeping with the idea that smaller was better, statewide branch banking was prohibited in most states, but not in California. By the late 1940’s California was the fastest growing state in the union, and Gianni hitched his wagon to that growth. Opening branch after branch, Bank of America grew to more than 500 branches by the time of Gianni’s death in 1949. Yet behind that ubiquity Gianni’s founding principles remained, a dedication to the little guy that would outlive its founder and find new expression in the fledgling Central Valley city of Fresno.

The Thing About Fresno

Fresno began life as a train depot and country store. It was incorporated in 1885 and grew in population as families and farmers were drawn to the Fruitvale Estate, a unique residential subdivision and raisin plantation where fencing and irrigation were provided cooperatively, allowing small plot farmers to lead a middle class life. From the beginning, Fresno was ethnically diverse with Germans, Italians, Armenians, Chinese and Japanese taking up residence there. But it wasn’t the differences among people that attracted Bank of America to Fresno. It was the thing one thing so many of them had in common, where they banked.

A Cockamamie Idea

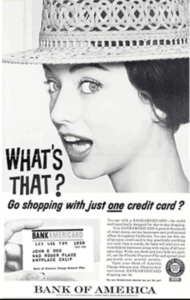

By the late 1950’s the growing demand for installment loans by American consumers gave Bank of America a new idea. Why not offer a line of credit to consumers in the form of a card that would allow them to purchase anything they wanted up to a certain credit limit? By this time, consumers were already familiar with gas station and department store credit cards, but Bank of America wanted to go further. They wanted to give consumers the freedom to buy anything they wanted, without a loan officer’s oversight.

Bank of American wanted to give consumers an unsecured loan to buy anything they wanted. It seemed like madness.

This was revolutionary, if not downright reckless. When businesses defaulted on their loans, the bank knew where to find them. What’s more, business loans were secured with collateral. What Bank of America was proposing was to make unsecured loans to consumers. It seemed like madness. Indeed, many merchants were suspicious. When the sales people at BofA approached merchants to persuade them to accept the cards, most resisted. It wasn’t just that the whole idea seemed cockamamie, there was also the fact that most people didn’t carry the cards, which meant there weren’t enough users to make it worthwhile for the merchants.

BofA’s solution to the problem of reluctant merchants was an unsolicited mass mailing of thousands of credit cards directly to consumers, no questions asked, what became known as “a drop” in banking jargon. But for the drop to work BofA needed a particular type of community, one with a large enough population to provide the critical mass of card holders to get merchants interested, one that was fairly isolated (so consumers wouldn’t take their buying power out of town), and, most importantly, one where a plurality of citizens banked with BofA. As it turned out, Fresno was perfect.

The Drop

In 1958 a whopping 45% of Fresno’s 250,000 people were doing at least some business with BofA. The plan was to drop 6,000 unsolicited credit cards to the most credit worthy among them, and, on the strength of that, BofA was able to sign up more than 300 merchants to accept the cards. They called the new card BankAmericard.

In September of that year the drop went off without a hitch. You can imagine the surprise of those receiving the cards. Here, out of nowhere, a bank was offering them an unsecured line of credit to buy anything they wanted. All they had to do was walk into a store and plunk down a piece of plastic. It was like pennies from heaven. People were mesmerized by it. It was like a magic trick. When card holders pulled out their cards to pay, other customers gathered around, mouths open, to watch the transaction.

Of course, it wasn’t free money; the interest rate was 18% per annum, and the card holder had thirty days to pay before the interest set in. But for the most part the good people of Fresno understood and cooperated. The whole thing might have been regarded an unqualified success if it had just stayed In Fresno, but it didn’t.

Disaster

Even before the results from Fresno were in, BofA got antsy. They figured the only way their BankAmericard was going to work was if enough consumers had the card, which would, in turn, lure in more merchants. Such was the skepticism among merchants that there was no way more than one card was going to be accepted. There was no room for competition. Then BofA got wind of a competitive bank’s imminent plans to unveil a competitive card.

Reacting in kneejerk fashion, BofA quickly expanded its efforts beyond Fresno, dropping cards in Bakersfield and Modesto. Six month later it was dropping cards in San Francisco and Sacramento. And within a year it was dropping cards in Los Angeles. One of the reasons Fresno was chosen as a test market was because of the wholesome, upstanding nature of its citizens. These were people who could be counted on to pay their bills and not go delinquent. There were no such feelings about the people of Los Angeles.

The Thing About Los Angeles

The Los Angeles drop exposed BofA’s pollyannish view of consumer integrity. What they had predicted would be a 4% delinquency rate turned out to be 22%. BofA was so sure American consumers would rather die of shame than fail to meet their financial obligations that they never even bothered to set up a collections department. And then they found themselves having to collect. Fifteen months after its launch, BofA’s credit card program had lost $8.8 million. To add insult to injury the competitive card they had been trying to get ahead of never materialized. The whole exercise turned out to be a disaster.

Learning From Their Mistakes

A different bank might have walked away from the burning wreckage of its starry ambitions, but not BofA. The founding philosophy of A.P. Gianni still exerted a powerful pull on the bank’s managers. They were still driven to serve the little guy, and the credit card seemed the most obvious path to that purpose. True, everything that could go wrong had gone wrong with BankAmericard, but they could learn from their mistakes and move forward with the enterprise, which they did.

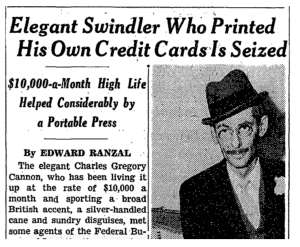

Ironically, the fallout from the disaster made things easier for BofA. By scaring off potential competitors from copying them, BofA had the credit card business all to itself for the next seven years. In that time, they cleaned up their mess. Cards were taken out of the hands of bad apples, losses were written off, a collections department was established, and fraud was hunted down and dealt with.

By 1964 the public was warming to the idea of credit cards, more than 400,000 were in circulation. Two years later that number jumped to a million. In 1970 BofA formed a consortium with its other issuing banks to take over management of BankAmericard, at which point they changed its name. They rechristened it Visa.

Fresno, CA and the Birth of the Credit Card

As the credit card took off, Fresno declined. Downtown Fresno today is a rundown backwater in desperate need of urban renewal. The Bank of Italy building is boarded up. The population has moved to the suburbs.

But in the 1950’s Fresno was a poster child for American prosperity, a city ideally suited to act as an incubator for an ambitious new financial product, one designed for the common man, one that relied on the innate integrity of its users, and one that needed a good-sized California city, remotely located to make it work. Fresno may be the red-headed step-child of California cities, but Fresno never failed Bank of America. For a brief time in autumn 1958, Fresno stood in for all of America. It was everywhere they wanted it to be.

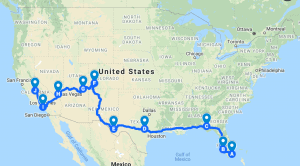

Previous stop on the odyssey: Los Angeles, CA //

Next stop on the odyssey: San Francisco, CA

Sources

Kearny, Theo M. Fresno County, California and the Evolution of the Fruit Vale Estate. Fresno, CA. Franklin Classics Trade Press. 13 November 2018.

Nocera, Joe. A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class. New York, NY. Simon and Schuster. 15 October 2013.

Image credits:

Four credit cards, “Credit Cards”, Sean MacEntee

Bank run in the 1930s’, Public Domain

Happy housewife, Public Domain

GE Automatic Washer Ad, by SensaiAlan

A.P. Gianni, Italian American Museum of Los Angeles

Bank of Italy building in Fresno, Malcolm Logan

Main house of fruit vale estate, Malcolm Logan

What’s That? Advertisement. Visa history

As Good as Cash, Public domain

Elegant swindler news story, cucollector.com

Los Angeles in the 1950’s, Bizarre Los Angeles

Downtown Fresno today, Malcolm Logan