The horrors of Andersonville Prison rival anything seen at the Nazi death camps. But this happened here in America, at the hands of Americans.

When they came to Wirz with the offer, he refused them. He was not a man to play games. He had already told them he knew nothing that would implicate President Jefferson Davis in the calamity that was Andersonville, but they kept pressing him, thinking he would crack, thinking he would bear false witness in order to save his own skin. He would not.

Wirz was hanged on November 10th, 1865. His neck didn’t break in the fall, and he writhed and suffocated at the end of the rope, his hands tied behind his back. The crowd of 250 cheered at first but grew somber as the grisly ordeal played out, the clock ticking. It was like Andersonville itself, needless suffering that seemed to drag on and on. At last his body shuddered and went limp.

A Scene of Horror

Turning off I-74 near Henderson about two hours south of Atlanta, I drove 30 miles through the pine and sassafras country of southwest Georgia to Andersonville National Historic Site, a 26.5 acre historic park where a part of the stockade wall from the notorious prison has been reconstructed.

Here, in 1864 and 1865, 45,000 Union soldiers were imprisoned in deplorable conditions to rival anything seen in the Nazi extermination camps. In fifteen months 13,000 died of disease, starvation, and exposure. They were buried in mass graves. Their commandant was Captain Henry Wirz.

The 15-foot stockade wall was the extent of the construction at Andersonville. Barracks were never built. Prisoners remained penned up like cattle.

The 15-foot tall stockade wall was meant to be a temporary holding pen while officials built wooden barracks for the prisoners transferred here from other POW sites across the south, but the reason for the transfer was the same reason the barracks never got built.

By 1864 the Confederacy was collapsing, Union troops were closing in. To prevent their liberation, prisoners were hastily transferred here to the deepest part of the deep south while every available Confederate soldier was sent north to confront the enemy. Little remained in the way of men and material to build barracks for enemy prisoners. So the prisoners remained penned up like cattle, living in canvas tents, at the mercy of the elements and suffering the conditions.

Up Against the Deadline

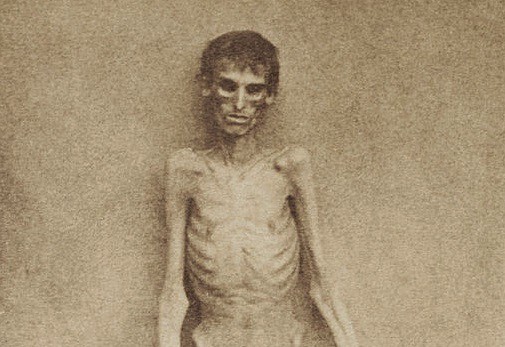

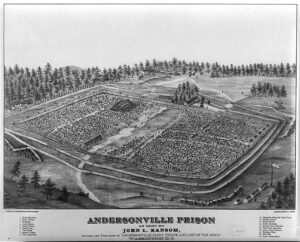

This stunning image from 1864 shows the overcrowding. This was still early. A year later even more prisoners had arrived and most were starving.

The only source of water at Andersonville was a torpid stretch of Sweetwater Creek that ran through the prison yard. From this the prisoners took their drinking water and deposited their waste. Prisoners were forced to bathe in the foul sink. Many died of dysentery.

As the war dragged on, more and more prisoners arrived until, by the end of June 1864, the prison held 26,000 men crowded together in an area designed to hold 10,000. At its peak the prison housed 33,000 men, making it the fifth largest city in the Confederacy. They were virtually on top of one another.

The close quarters and desperate conditions led to theft and violence. Gangs formed, chief among them the Andersonville Raiders, a marauding group who attacked their fellow prisoners with clubs and knives to steal their food and clothing.

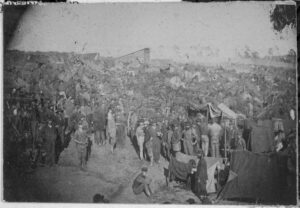

13,000 died at Andersonville. They were buried in mass graves. Here the grave diggers pause to be photographed.

The horrors of the camp made many men long to escape, but a short single-rail fence called “the deadline” marked a boundary 19 feet inside the stockade wall they dare not cross. Any prisoner caught stepping across the deadline was shot from one of the guard towers lining the wall.

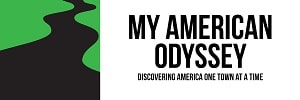

Violence, overcrowding, disease. But the worst hardship imposed on prisoners at Andersonville was the lack of food. Many starved. When finally liberated, the survivors wore the ghostly, emaciated looks of holocaust survivors. But these were not European Jews condemned by Hitler’s Reich. These were Americans brutally abused by other Americans, chief among them Henry Wirz.

Wirz’s Point

Captain Henry Wirz was one of only two men tried, convicted, and executed for war crimes during the Civil War. He was charged with conspiring to impair the lives of Union soldiers, a nice way of saying that he was accused of killing the prisoners in his charge. He vehemently rejected the charge, and not without justification.

Captain Henry Wirz was one of only two people accused and convicted of war crimes in the Civil War. Rightly or wrongly, he was held responsible for the debacle at Andersonville.

Part of the Union strategy in the waning days of the war was to starve the Confederacy into submission. This meant Union armies destroyed farms and factories, ripped up railroads, blockaded ports, and blew up bridges in an effort to prevent the movement of food and medicine to confederate troops. The South itself was slowly starving, so it is not surprising that the last people on the long list of those waiting to be fed were Union prisoners of war.

The only hope for those suffering at Andersonville was a prisoner exchange, a not uncommon occurrence in the early years of the war, but something increasingly rare as the North gained the upper hand. The war of attrition being prosecuted by the North on the South was designed to deplete the enemy’s manpower. So they were certainly not going to give any prisoners back.

Yet that didn’t keep Henry Wirz from specifically requesting a prisoner exchange from Union authorities to relieve the overcrowding at Andersonville. His request was denied.

In a very real sense, the prisoners at Andersonville were victims of their own government’s war strategy. Which was precisely Wirz’s point.

The Endless Procession of Victims

This image was taken only moments after Wirz dropped through the gallows door. His death was as gruesome and sobering as the events that had brought it about.

But this didn’t get Wirz off the hook. At war’s end a military tribunal, one of the first in the nation’s history, was convened to try Captain Wirz for war crimes. It heard the testimony of former inmates, officers and townspeople.

For six weeks in the late summer of 1865 Wirz’s trial was front page news across the nation. Wirz was depicted as a cruel martinet, threatening to personally shoot any prisoner who tried to escape, quick to clamp any prisoners who displeased him into irons.

Having suffered a long war brought on by Southern intransigence and unwillingness to compromise, the people of the North were looking for revenge and Wirz was a handy target. Still, he might have escaped the gallows if not for the testimony of one man, a mysterious individual named Felix de la Baume, who claimed to be a direct descendent of the Marquis de Lafayette, a hero of the Revolutionary War, a true American.

An aerial illustration of Andersonville prison in 1865. So strong was the public outcry against the conditions there, someone had to pay.

De la Baume told a heartrending story of Wirz’s cruelty, giving a first hand account of the murder of a starving prisoner at Wirz’s hands. A few weeks later the tribunal returned its verdict and Wirz was condemned.

The night before his execution, federal officials came to him in secret and made an offer. They would stay the execution if Wirz would agree to implicate Jefferson Davis in the horrors of the camp. Wearying, perhaps, of the long procession of victims, Wirz refused.

After his death, it emerged that Felix de la Baume was a fraud. His testimony had been cooked up to rouse Northern passions for his execution. Wirz had become a victim of Andersonville as well.

Today, the strong belief that Wirz had been made a scapegoat for the atrocities at Andersonville has led some in the region to erect a memorial in his honor. Each year they march there, asking the government for a congressional pardon for Wirz. Nearly 150 years later, the pardon has still not been granted.

Site of Andersonville prison today. This site also includes the National Prisoner of War Museum, a memorial to all American prisoners of war.

Andersonville

Prisoners of war are victims of the cruelest fate. Captured and kept alive, they become the victims not only of their captors, but of their own country’s war aims. For if their country enjoys success, their own suffering will almost certainly increase, which means the closer they get to liberation, the closer they get to extermination. The thing most to be hoped for is often the thing most to be feared.

The National Prisoner of War Museum at Andersonville National Historic Site honors all American prisoners of war. Using art, photography and video, the museum highlights the grim experiences of prisoners of war throughout American history. It is a sobering experience.

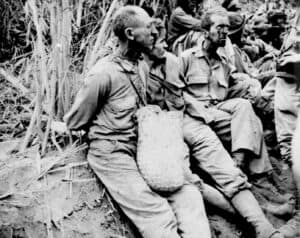

The National Prisoner of War museum honors all American POWS, like these victims of the Bataan Death March in the Philippines during World War II.

Few experiences are as grindingly depressing as that of being a prisoner of war. The self-contempt that comes with the question of why you survived while others perished is amplified by the POW experience. Humiliation, cruelty and dehumanization are common. The act of survival becomes less a matter of self-preservation than an act of defiance against those who would be relieved by your demise. Having lived, you become dead.

The Dark Camps of War

Certainly the prisoners of Andersonville experienced such desolation. And those who perished might have suffered the further indignity of having been forgotten if it weren’t for the efforts of Dorence Atwater, a prisoner at Andersonville who made a copy of Confederate prison records, listing the names of those who had died. After the war was over, it was Atwater’s list that permitted federal officials to mark the gravestones at Andersonville.

The cemetery at Andersonville. Fortunately most of the victims were identified, their names etched on the tombstones.

As I stood there, looking out at the 13,714 gravestones that flowed out and over the surrounding countryside, I felt a tug in my heart for the thousands who had died, not in the glory of the fight but in the misery of a slow death, and the soul crushing experience of being a prisoner of war.

When we honor our war heroes with medals and flags, we would do well to remember the bleak underside of that martial display, the tens of thousands gutted and discarded by the experience of having been prisoners, the long procession of victims in the dark camps of war.

Check it out…

Andersonville National Historic Site

Andersonville National Historic Site

706 POW Road

Andersonville, GA 31711

Website

Previous stop on the odyssey: Africatown, AL //

Next stop on the odyssey: Winnsboro, SC

Sources:

Andersonville National Historic Site – Park Statistics (U.S. National Park Service)”. Nps.gov. Retrieved December 2012.

Andersonville Prison, Civil War Trust, Civilwar.org, Acquired December 2012.

Andersonville: Prisoner of War Camp – Reading 1. Nps.gov, Acquired December 2012.

Peoples, Morgan D. “Henry Wirz: The Scapegoat of Andersonville”, North Louisiana History, Vol 11, No 4 (Fall 1980)

Image credits:

Andersonville survivor, Public domain; Stockade wall at Andersonville, Bubba73; Overcrowding at Andersonville 1864, National Archives; Mass grave at Andersonville prison 1865, National Archives; Captain Henry Wirz, Public domain; The execution of Henry Wirz, Public domain; Aerial illustration of Andersonville prison, Public domain; Tents at Andersonville Prison site, Tara Cooper; Bataan Death March prisoners, Public domain; Andersonville cemetery, Bubba73; Providence Spring at Andersonville National Historic Site, Tara Cooper