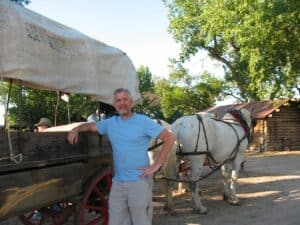

Even wagon drivers on the Oregon Trail sometimes preferred to get down and walk. Riding in a covered wagon is a jostling, jarring experience.

It was perfectly logical to believe. After all, the Rhine connected with the Danube via the Main and a short portage, tying together the entire European continent. The Nile ran for an astonishing 4,000 miles deep into central Africa. So why wouldn’t the Missouri flow from the Mississippi all the way to the Pacific Ocean?

If it did, it meant the entire North American continent was connected by water, the implications of which were staggering. It meant the American west could be opened up for commercial and agricultural development. It meant goods manufactured in the east could find a market deep in the interior.

President Thomas Jefferson wanted to know, so he dispatched Lewis and Clark in 1804. But after following the Missouri River to its source, more than 2,000 tantalizing miles to the northwest, they came back with bad news. There was no all water route to the Pacific. The prospects for opening the west briefly dimmed.

Once a wagon road was established, it became clear that getting to Oregon would be a matter of rolling there on wheels.

Shangri-La Among the Evergreens

In 1818 the United States and Great Britain attempted to bury the hatchet after 40 years of intermittent warfare by signing a treaty marking the boundary between the U.S. and Canada at the 49th parallel. The Treaty of 1818 allowed for several exceptions, most notably the joint occupation of the Oregon territory (present day Oregon and Washington states). It wasn’t long before British and American settlers were trying to push each other out.

Most pioneers didn’t actually ride in the wagons. Instead, they walked along beside them – for 2,000 miles!

The British solution was to eradicate all the fur-bearing animals in the region, thus discouraging Yankee fur traders from seeking their fortunes there. The American solution was simpler, and quintessentially American: to flood the Pacific Northwest with Americans. Great in theory, but getting to that faraway place proved problematic. Without a river route, the settlers had two choices. They could travel by ocean down the coast of South America, around Cape Horn, and up the west coast of two continents, a distance of 14,700 miles. Or they could attempt to travel overland, a grueling journey across 2,000 miles of forbidding prairies, deserts and mountains.

Still, the powerful lure of Oregon drew people on. If ever a land had the appeal of Shangri-La, this was it, a fertile, disease-free climate, extensive uncut forests, crystal clear rivers swarming with fish, abundant game, friendly natives, ocean access, and plenty of land free for the taking. All you had to do was get there.

What Good is the Platte?

The Platte River for much of its length is a shallow, meandering brook running down a broad, sandy river bed too shallow to float a boat in.

As early as 1810 American fur trading mogul, John Jacob Astor, outfitted an exhibition to blaze an overland route to Oregon territory. His team made it across the Grand Tetons to the Snake River in modern day Idaho before having to abandon the river and bushwhack their way to the Columbia River in what is today western Washington State. They passed on what they learned from the experience to those who came after them.

Like programmers tweaking open source software, these early explorers built on those who went before them, always seeking improvements and efficiencies. One thing the fur traders discovered, much to their vexation, was that one of longest rivers they encountered, a river that ran straight west in the direction they were headed, was also unnavigable.

Fort Kearny functioned as way station for pioneers along the Oregon Trail. At its height 2,000 emigrants a day passed through here.

The Platte River for much of its length is a shallow, meandering brook running down a broad, sandy river bed that, if it was filled to its banks, would be an estimable waterway. Sadly, it rarely fulfills its promise. Anyone attempting to float down its length would find himself carrying his boat much of the way.

Still, the Platte does provide a source of drinking water, and the river does run through flat, easily sloping country, making it an ideal artery along which to set a wagon road, which is precisely what the early explorers did. That wagon road became the Oregon Trail.

What was needed for the long cross-country trip was a vehicle that could carry plenty of supplies, and could double as shelter along the way, sort of a mobile tent.

RV’s of the 1800’s

Once a wagon road was established, it became clear that getting to Oregon would be a matter of rolling there on wheels. But what kind of wheels? The logical choice for the rugged country ahead would be a two-wheeled cart of the sort used in Mexico. Such carts had the advantage of being able to trundle along easily over rugged ground but were limited by the amount they could carry. What was needed for the cross-country trip was a vehicle that could carry plenty of supplies, and could double as shelter along the way, sort of a mobile tent, the 19th century version of an RV.

The covered wagon of the time was basically a long wooden box on wheels with sides about two feet high and a canvas top rising to a height of five feet that was stretched over several bows of bent hickory. The canvas was waterproofed with paint or linseed oil to keep the contents dry. The emigrants themselves often got soaked. A common misconception about the pioneers is that they rode along in their wagons. For reasons that will become clear in a moment, they rarely did. Instead, they walked beside them. It’s astonishing to consider that over the 2,000 miles that comprised the Oregon Trail the emigrants walked most of the way.

The wagon was pulled by a team of oxen, between four and eight animals yoked two abreast. At one-third the cost of mules, oxen were preferred, particularly as the probability of losing an animal was great.

The trek from Independence, MO to Oregon City took more than five months. Bayard, NE is where the map turns from yellow to gray, from grassland to more arid country.

The trek from Independence, Missouri to Oregon City took more than five months, during which time an ox could die of disease, of drinking alkaline water, of thirst, of slow starvation, or of being overworked. The loss of an ox was worrisome because the additional strain it put on the remaining team could endanger them as well. To avoid this calamity the load would have to lightened, putting the emigrants in the unenviable position of deciding which essential supplies to leave on the trail behind them.

The Oregon Trail was littered with all sorts of discarded stuff, evidence of the pioneers’ desperate attempts to keep their oxen from dying. Under such circumstances, riding in the wagon would be be ill advised at best.

Chimney Rock is a 325 foot natural geological feature that served as a prominent landmark along the Oregon Trail.

Hazards of the Oregon Trail

Death and disaster lurked everywhere. Wagon tongues and axles broke with maddening regularity, forcing emigrants to fashion new ones on the spot from whatever trees could be felled in the immediate vicinity. In barren country finding a good tree could delay an emigrant party for days. Carrying spare tongues or axles was out of the question as they added too much weight, not only endangering the oxen, but also slowing the emigrants’ progress, which carried its own dangers.

There was a short window. The emigrants generally left Missouri in May and strove to get through the Rockies before October. A delay could put them in the mountains as the snow began to fall, and as the Donner Party learned to their horror, winter in the mountains could be a death sentence. But setting out in May had its own hazards. It put the emigrants on the Great Plains during the height of summer when the sun beat down like a hammer on an anvil. Thirst was a constant companion. Carrying too much water, however, added extra weight. So the emigrants fended for themselves along the way. Beyond the Platte River , however, finding potable water could be tricky and drinking from the wrong waterhole could be deadly.

River crossings were perilous. Fast flowing rivers could smash a wagon to splinters. Steep descents were nerve-wracking. Wagons didn’t have brakes and had to be lowered by ropes. One slip and it was all over.

A wagon damaged beyond repair would have to be abandoned, throwing the emigrants on the mercy of their fellows, adding to the friction that inevitably occurred in close quarters over long distances. Quarrels were common. Fights broke out, adding another potential source of hardship. An injured or sick person was an added burden and was deeply resented. Snake bite, disease and Indian attack presented further dangers, so that surviving the trek seemed like a miracle. But in the end most emigrants made it through.

Getting a Taste of the Oregon Trail

At The Oregon Trail Wagon Ride, 21st century types get a taste of what it was like to ride in a covered wagon.

To get a taste of the Oregon Trail I traveled with my wife along the Platte River in western Nebraska and stopped at the Fort Kearny State Historical Park. Fort Kearny functioned as way station, sentinel post, supply depot, and message center for emigrants traveling west on the Oregon Trail in 1850’s. During its height it saw as many as 2,000 emigrants passing through daily.

From there we traveled another 125 miles west to the Chimney Rock National Historic Site near Bayard, Nebraska. Chimney Rock is a 325 foot high natural geological feature that served as a prominent landmark along the Oregon Trail. requently mentioned in pioneers’ journals, the impressive spire was significant as the point at which the grasslands would give way to more arid soil as the country rose in elevation.

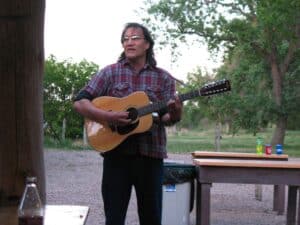

Finally we stopped at The Oregon Trail Wagon Ride in Bayard. This family friendly attraction features a covered wagon ride, a chuck wagon dinner and a cowboy sing-along . We strolled along the Platte River, enjoyed a juicy steak, and sang cowboy songs like “Whisperin’ Wind” and “Oh, Nebraska”. But the highlight was the wagon ride.

Covered wagons did not have springs for suspension. The wheels were made of wood and the tires were made of iron. Riding in one is a jostling, jarring experience. or early pioneers who were breaking trail, the experience would’ve set teeth to clattering. Yet another reason they chose to walk.

The British Throw in the Towel

We played a game of horseshoes while we waited for the steaks to grill at The Oregon Trail Wagon Ride.

The great period of overland emigration lasted just thirty years.

In 1840 the Meek-Newell party became the first emigrants to reach the Columbia River in Oregon traveling exclusively by wagon. A year later, the Bartleson-Bidwell party became the first to use the Oregon Trail over its entire length. In 1842 the White party proved that a large group consisting of more than 100 pioneers could make the journey successfully, which ushered in the year 1843, the year of The Great Migration, when an estimated 1,000 emigrants, in groups large and small, made the journey to Oregon. The flood gates were open.

Steaks on the grill for a group of about 30. Beans, potatoes, home baked bread and cowboy coffee rounded out the menu.

Three years later, in 1846, the British, whose fur trading enterprise was in steep decline, and whose attempts to lure eastern Canadians to the territory had floundered, agreed to end the experiment in joint occupation by signing the Oregon Treaty, which extended the 49th parallel as the US-Canadian border all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Present day Oregon and Washington State were now firmly within US jurisdiction.

Ironically, however, within three years, emigrant interest in Oregon territory fell off sharply. In January 1848 gold was discovered in the American River in Northern California. By the end of the year, two-thirds of the male population of Oregon had gone to California. By the following year tens of thousands of Easterners headed off eagerly down the Oregon Trail, not for Oregon, but for California.

The Trail’s End

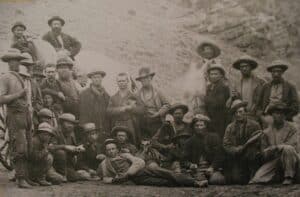

The early 1850’s saw use of the trail at its peak as thousands of emigrants headed westward not to Oregon but to California, like this group of Forty-Niners.

The early 1850’s saw use of the trail at its peak, which brought all sorts of new hazards. With so many people using the same springs and watering holes, sanitation became a problem and cholera broke out. Increased traffic also brought desperadoes. Emigrants got held up at gunpoint and relieved of their possessions. The plains Indians, who had viewed the early emigrants as mere curiosities, began to bristle at the ever-increasing tide of white settlers encroaching on their lands. What had always been dangerous became more so.

By 1859 gold fever was on the wane, and then the Civil War broke. During the war, use of the trail declined. With the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 it fell off sharply. Throughout the 1870’s and 80’s portions of the trail were still being used by settlers moving west. Several offshoots and side trails carried easterners to new homes throughout the plains, but the trail’s original purpose as a conduit for moving emigrants west to Oregon had long since passed.

Today Interstate 80 follows roughly the same route as the Oregon Trail through much of Nebraska. US Highway 26 and Interstate 84 in Idaho and Oregon also parallel portions of the trail. As a symbol of America’s determination to expand west in spite of all obstacles, the Oregon Trail tells an inspiring story. The sheer grit it took to walk 2,000 miles across difficult territory to reach a promised land in Oregon is impressive. It speaks of a drive and tenacity at the heart of the American spirit.

As it turned out, an all water route to the Pacific was a pipe dream. Instead, Americans had to walk across a continent and face of all sorts of hardships to get where they were going. But that didn’t stop them. Heck, it didn’t even slow them down. They just threw out their extra baggage and kept going.

Check it out…

Fort Kearny State Historical Park

Fort Kearny State Historical Park

Route 4

Kearney, NE 68847

308-234-9513

Website

Chimney Rock National Historic Site

Chimney Rock National Historic Site

1.5 miles south of Hwy 92

on Chimney Rock Rd

Bayard, NE 69334

308-586-2581

Website

Oregon Trail Wagon Ride

Oregon Trail Wagon Ride

Rt 2 Box 502

Bayard, NE 69334

(308) 586-1850

Website

Previous stop on the odyssey: Badlands, SD //

Next stop on the odyssey: Stanton, MO

Image credits:

All images by Malcolm Logan, except Women standing beside cover wagon, Public domain; Fort Kearny stockade, C.S. Imming; Oxen pulling covered wagons, Public domain; Oregon Trail map, Mattes; Forty-niners on the Oregon Trail, Public domain; Wagon train, Public domain

1 comment

Dear Malcolm!

I found your report about the Oregon Trail online and read it with great enthusiasm. I’m in the early stages of planning a film project about the Oregon Trail and hence, I had many questions concerning it. Luckily, your essay was able to answer some of them.

If you’re interested in discussing the Trail in regards to my project, please get back to me.

Malte from Germany