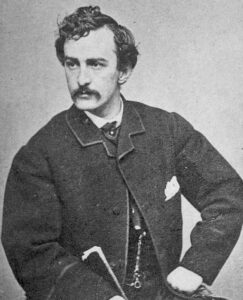

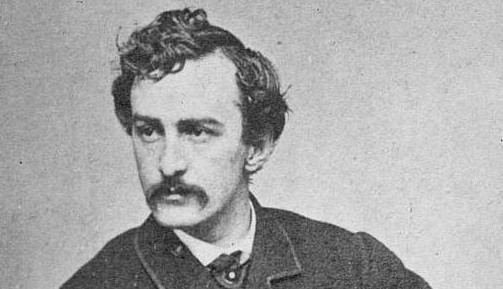

John Wilkes Booth was the Brad Pitt of his day, a handsome, wealthy celebrity who could make the ladies swoon.

Just after 4:00 in the morning of April 15th, 1865 two men appeared on horseback at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd near present day Waldorf, Maryland. One man was suffering a broken leg and needed help. Dr. Mudd helped the injured man into his house, cut away his boot and set the leg. The two men then spent the rest of the night and most of the next day in Dr. Mudd’s house.

But when federal troops arrived later to question Dr. Mudd about the assassin who had killed President Lincoln and taken refuge in his home, Mudd insisted he had not recognized John Wilkes Booth, this in spite of the fact that he had met Booth four months earlier and spent the better part of two days with him. Was he lying?

Implausible as it may seem, descendants of Dr. Mudd, who still own the house and have opened it for tours, have spent the better part of the last 150 years trying to clear his name. As you are shown around the house, the docent is at pains to convince you of Mudd’s innocence. You can see the room where Wilkes Booth and his accomplice slept that night, and, most remarkably, you can see the actual settee where Booth lay to have his leg set, but courtesy restrains you from expressing skepticism about their claim.

Booth’s assassination of Lincoln was not well planned. He basically threw the plot together at the last minute after his original plans had fallen through.

Whether or not Booth was in disguise, as his ancestor’s claim, it’s hard to believe the doctor could have been in such close contact with his patient and not recognized him; and the fact remains, after Booth and his accomplice left the house the next day, Dr. Mudd did not immediately report the incident to the authorities in spite of the fact that the whole countryside was aroused with news of the assassination and the flight of the murderer.

The sensitivity of Mudd’s descendants on this issue is testimony to how close to the surface these matters still are to an event that happened more than a century and a half ago. Part of the reason may be that the Lincoln assassination was the final act in a terrible drama that started with our politicians’ refusal to compromise and ended with a bloody war that claimed 620,000 American lives.

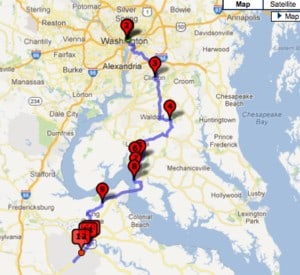

John Wilkes Booth escape route. Click the map for greater detail and to zoom and shift over territory.

Another reason may be that the landscape and locations of Booth’s escape route remain largely unchanged from that time, lending an air of immediacy to the events. With a few notable exceptions, you can see almost every spot on Booth’s escape route from Ford’s Theatre in Washington to his assassination site near Port Royal, Virginia much as Booth saw them.

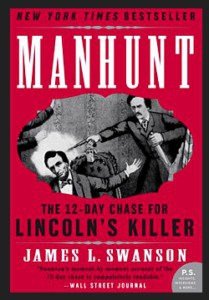

If you’re in Washington DC and you have a day to spare, it’s fascinating and worthwhile to follow Booth’s escape route through Maryland and into Virginia, and if you want the perfect companion to help fill in the blanks, take along James L. Swanson’s compelling book, Manhunt, the 12 Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer.

Mary Surratt’s Boarding House

Begin your tour of John Wilkes Booth’s escape route in an unlikely place, the Wok n’ Roll restaurant in Washington DC’s Chinatown. The Chinese restaurant is housed in the actual building that was Mary Surratt’s boarding house in 1865, and was the frequent meeting place of Booth and his co-conspirators in their plot to kidnap Lincoln.

Mary Surratt’s boarding house as it appears today. It’s the Wok n’ Roll restaurant. (Click any picture to enlarge).

Yes, that’s right. Booth’s assassination of Lincoln was Plan B. The original plan was to kidnap the president and hold him for an exchange of confederate prisoners. But when the war ended and prisoners on both sides were released, Booth’s original plan fell apart. In an act of desperation he cobbled together the assassination scheme at the last minute, dragging along a few halfhearted conspirators.

After the assassination, federal troops descended on was Mary Surratt’s boarding house. Mary was arrested and convicted, becoming the first woman to be executed by the federal government. But Booth was not there. He had escaped to Maryland.

Ford’s Theater

Walking time from the previous stop: 10 minutes

Ford’s Theater in Washington has been restored to the original condition it was in on the night of the assassination on April 14th, 1865. An interesting museum detailing the events of the assassination is housed on the lower level but the highlight is the National Park Service lecture about the assassination given from the stage as you sit in the theater seats, gazing up at the box where the assassination occurred.

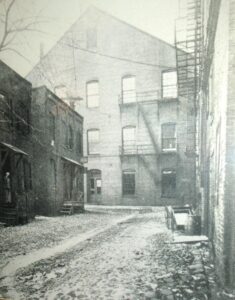

The theater lecture is usually thronged with tourists, but another interesting spot where few tourists go is the alley behind the building where, on the night of the murder, Booth struggled up onto his horse after breaking his leg leaping from the box after killing Lincoln, shouting in Latin, “Thus, always to tyrants!” The horse had been held by a young peanut vendor who handed it over to Booth as soon as he hobbled out the back door, and it was lucky for Booth he did, for Booth was pursued by a concerned citizen named John B. Stewart who tried to drag Booth from his horse. Booth fought back and escaped Stewart, galloping away up the alley. Today, the alley looks much as it did in 1865.

Surratt’s Tavern

Driving time from previous stop: 25 minutes

Booth rode hard for the Potomac River bridge near present day Anacostia. Once at the bridge, he used his skills as an actor to persuade the watchman to let him pass. Once over the bridge, Booth rode off into the open, isolated country of southern Maryland.

It is a testament to Booth’s charm and prowess as an actor that he was able to persuade the watchman to let him pass; the watchman had firm orders not to let anyone through. But Booth was a consummate thespian and matinee idol. Far from being unknown to the people of Washington, Booth was the Brad Pitt of his day, a handsome, wealthy celebrity who could make the ladies swoon.

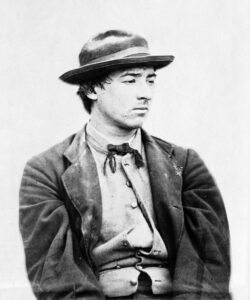

Booth’s accomplice, David Herold, was star struck by Booth and remained with him through most of the ordeal.

On entering Maryland, Booth made first for Surratt’s Tavern near present day Clinton, MD about 12 miles south of Anacostia. The tavern had been a safe house for the confederate underground and was the home of John Surratt, son of Mary Surratt and a member of Booth’s original conspiracy to kidnap the president.

Today Surratt’s Tavern is fully restored and presided over by a docent in period dress. A tour of the boarding house shows you the rooms where the boarders stayed, the kitchen and the dining room, and the place where Booth had hidden a pair of rifles between the walls in anticipation of his flight.

It was fortunate that two rifles had been stashed there because in his flight south from the river Booth picked up a traveling companion, David Herold, a co-conspirator whose role would be to act as a guide for the assassin through Maryland.

The home of Dr. Samuel Mudd is still flying the confederate flag. Was Mudd an accomplice or a dupe as his ancestors claim?

Booth and Herold only lingered at Surratt’s Tavern long enough to pick up the rifles and bolt down a bottle of whiskey. While there Booth couldn’t resist the urge to boast that he had killed the president. Maryland had been a hot bed of secession before the war and was only kept in the Union through hook and crook. Booth might have hoped that the news would be met with hearty congratulations, but by the end of the war many former confederates had had their fill of bloodshed and were less than enthusiastic about the news. Booth likely did not receive the accolades he had been hoping for.

Samuel Mudd House and Museum

Driving time from previous stop: 20 minutes

By some accounts, Dr. Samuel Mudd angrily ordered Booth and Herold to leave his home as soon as he discovered that they had been involved in the President’s murder. But of course this would assume that Mudd knew who Booth was, an assertion firmly rejected by the Mudd family who oversee the Dr. Mudd House and Museum near Waldorf, MD, about 15 miles south of Surratt’s Tavern.

The dirt road leading away from the back of the Mudd house is the same road Booth and Herold traveled in 1865. It’s amazing how many things remain unchanged from that time.

The Samuel Mudd house remains almost exactly as it was a century and a half ago. As part of the tour you are shown pictures of Ft. Jefferson, a prison island in the Gulf of Mexico, 70 miles west of Key West, where Mudd spent four years in prison for his complicity in Booth’s escape. Mudd was pardoned by then president Andrew Johnson in 1869 after he courageously helped stem a yellow fever outbreak on the island. He died fourteen years later at age 49, by most accounts an exemplary citizen.

Since then the Mudd family has petitioned several successive presidents, requesting that the conviction be set aside, so far to no avail. It appears that forever after Dr. Mudd will wear the stain of his association with John Wilkes Booth. But he is not the only one.

Rich Hill and The Pine Thicket

Driving time from previous stop: 27 minutes

After leaving Mudd’s house, Booth and Herold showed up on the doorstep of Samuel Cox at his called home Rich Hill, near present day Bel Alton, about 18 miles southwest of Mudd’s farm. Today, the house still stands, nestled among the trees and surrounded by a clump of vegetation. It is a private residence and is not open for tours but can be viewed from the roadside.

Whether or not Booth and Herold ever actually entered the house is a matter of dispute, but what is known is that Cox, fearful of their presence, directed them down the road about a quarter mile to a pine thicket where they lay in hiding for the better part of a week. The pine thicket is still there today, although vastly diminished from its original size.

Booth and Herold camped out in this pine thicket for the better part of a week while federal troops mounted the largest manhunt in the nation’s history.

Nevertheless, one can get a sense of the setting where Booth and Herold remained, holed up and shivering, desperate and hungry, Booth suffering from the pain of his shattered leg, while thousands of troops pushed south out of Washington in pursuit of the fugitives. They had been advised to hide in that spot by the foster brother of Samuel Cox, a confederate agent who knew the surrounding countryside like the back of his hand. Cox had enlisted Thomas A. Jones to get Booth and Herold across the river to Virginia, which lay within the former confederacy, and where it was assumed they would be safe.

Huckleberry and the Potomac

Drive time from the previous stop: 7 minutes

Jones lived on a farm called Huckleberry. His home still stands, although today it is a Jesuit retreat house and can only be visited by appointment. The surrounding countryside is as tranquil and bucolic as it was in 1865.

The countryside near Thomas A. Jones farm, known as “Huckleberry”, is as tranquil and bucolic today as it was in 1865.

After five days, Jones returned to the pine thicket and advised the fugitives that it was time to go. He urged them to leave their horses behind, to be less conspicuous. They traveled on foot, by night, three and a half miles down a series of hidden paths and public roads to a marshy area near the outlet of Port Tobacco creek on the Potomac River where Jones had a row boat tied up and waiting.

The exact spot of Booth’s launch site is hard to pin down. There are some lively discussions about it online. But it makes sense that it would be directly west of Jones’ property near Huckleberry. About as close as you can get by car today is on Pope’s Creek Rd near the historical marker about a hundred yards past Captain Billy’s Crab House, which is an ideal place to stop and have lunch before carrying on with the escape route.

Thomas A. Jones led Booth and Herold to a secluded place on the Potomac River where he had a boat tied up and waiting.

In any case, you can get a sense of the wide expanse of the river and what Booth and Herold were up against in trying to cross it at night with no lights. Behind them, the countryside was filling up with federal troops—Dr. Samuel Mudd had already been confronted and questioned—so they couldn’t wait. When they shoved off, the night was as dark as ink. As a result, the two men became disoriented and got lost while crossing. After more than an hour, they ended up back on the east bank of the Potomac, still in Maryland.

David Herold sought out the home of a friend, who refused to let them in, telling them it was too dangerous. They were banished to the woods. After two more days of hiding out, Booth and Herold again attempted the crossing and finally landed in Virginia on the

morning of April 23rd, nine days after the assassination.

Cleydael

Driving time from previous stop: 25 minutes

Booth and Herold sought out the home of confederate agent, Elizabeth Queensberry, who arranged for them to be escorted to a Virginia plantation house 12 miles inland. The house was called Cleydael after the ancestral Scottish home of its occupants, Dr. and Mrs. Richard Stuart. It is still there today, although it is a private residence.

At Cleydael Booth and Herold got a chilly reception. Dr. Stuart grudgingly allowed them to eat dinner at his table but then sent them on their way, refusing to treat Booth’s leg. Booth was stunned at the way he was being treated. He had expected to be celebrated as a hero but instead was being shunted off as a pariah.

Instead of being welcomed into stately Cleydael, the fugitives were sent to the cabin of a freed black man, which infuriated Booth.

To add insult to injury, Stuart arranged for the fugitives to hole up for the night with a black man named John Lucas. John Wilkes Booth was a vicious racist and resented being relegated to the home of a black man. He forced Lucas and his family to sleep outside while he and Herold slept in the cabin.

In the morning, Lucas’s son Charlie transported the fugitives by wagon to the town of Port Conway on the Rappahannock River. He left them in the company of William Rollins, a fisherman who agreed to ferry them across the river, but not until he put out his fishing nets. While they waited, Booth and Herold were spotted by three mounted soldiers. Fortunately, for them they were confederate soldiers on their way home after the war. Booth and Herold fell in with the soldiers, and they crossed the river together.

At the Peyton House John Wilkes Booth was again turned away, this time due to the sensibilities of the ladies who resided there.

Peyton House

Driving time from previous stop: 15 minutes

Once on the other side of the river, in the town of Port Royal, one of the soldiers, William Jett, escorted the fugitives to the home of Randolph Peyton who he thought would be willing to provide them shelter. But Peyton was not at home, and his two spinster sisters thought it would be unseemly to have strange men residing in the house with them. Once again, Booth and Herold were refused admittance.

The Peyton house still stands on a side street in Port Royal, boarded up and sagging. A century and a half ago, Booth and Herold stood in its front yard and were informed that they were going to have to move on. They were advised to seek refuge at the farm of Richard H. Garrett three and a half miles to the south. Unbeknownst to Booth and Herold, this would be their last stop.

“Where Booth Died” reads the marker, but the marker is wrong. Booth actually died two miles south of here in a hard to reach spot between a divided highway.

Where Booth Died

Driving time from previous stop: 3 minutes

Garrett’s two eldest sons had just returned from the war, and Richard Garrett was in an expansive mood. When Booth and Herold were presented to him as returning confederate soldiers, Garrett welcomed them with open arms. At last Booth was getting the reception he felt he deserved. But things were about to change.

On Tuesday April 25th, one day after Booth and Herold passed through Port Conway, federal detective and manhunter Luther Baker arrived on the scene and questioned William Rollins, the fisherman who had been called on to ferry the fugitives across the Rappahannock. Rollins was forthcoming, describing the fugitives in detail. Baker felt sure he was hot on their trail, but to confirm it he wanted to question the soldiers that had reportedly been with Booth and Herold during the crossing.

Baker and members of the Sixteenth New York Cavalry tracked down William Jett in Bowling Green and, under threat of violence, persuaded him to reveal where Booth and Herold were hiding. Jett not only told them, he offered to take them there.

Meanwhile, the former hospitality shown by Richard Garrett toward the two supposed soldiers in his midst had soured when it became clear that Booth and Herold had been lying; they weren’t returning veterans but had taken advantage of the Garrett’s kindliness under false pretenses. Garrett’s oldest son, William, on discovering this, refused to let them sleep in the house. Once again, John Wilkes Booth, who had expected to be celebrated and embraced was being spurned. That night Booth and Herold slept in the tobacco barn.

After the rest of the tour, the Garrett Farm site is a bit of a letdown. It’s just a well trodden clearing in the woods with a sign warning against taking artifacts.

Today, finding the site of Garrett’s farm is tricky. The state has erected a historical marker just south of Port Royal, near the intersection of Route 301 and Route 17 that says Where Booth Died. But on reading the marker you learn “Booth died two miles south of here at Garrett’s farm.” So where exactly did Booth die?

Garrett Farm Site

Driving time from previous stop: 8 minutes

The former site of Garrett’s farm sits in a heavily forested median between a divided 4-lane parkway that cuts through Fort AP Hill, a 76,000 acre military base. ll along the way are signs prohibiting motorists from stopping or parking. What’s more, even though every stop on the escape route requires the traveler to travel further south to reach the next destination, to reach the Garrett farm site, the traveler must go south on Route 301 out of Port Royal for several miles, and then turn around and head back north on the other side of the divided parkway.

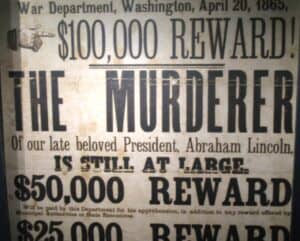

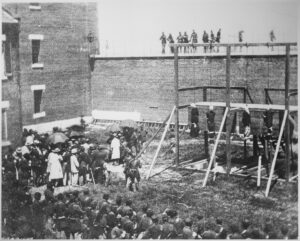

The manhunt raged for twelve days. In the end the reward money was distributed among the 26 cavalrymen that surrounded and killed Booth.

A lawn sign planted at the side of the road points the way up a path into the woods to the site of Garrett’s farm. It is difficult to park here as there is little or no shoulder and traffic is moving at a furious clip. The best you can do is get your vehicle over into the grass and leave it idling as you scurry up the path to take a look.

There’s really not much to see, just a clearing in the woods and a sign that warns visitors against taking artifacts from the site. If there were any artifacts to be taken, they are long gone. Of all the places along the escape route that are virtually unchanged from 1865, this place is so completely changed it’s hard to imagine what it was like on that April morning of 1865 when Booth and Herold woke up to find themselves surrounded by federal troops.

David Herold surrendered at Garrett’s Farm but was hanged three months later alongside Mary Surratt and two other conspirators.

Twenty-six cavalrymen took aim at the barn as detective Luther Baker ordered Booth and Herold to come out. David Herold emerged with his hands up, but Booth refused to surrender. After attempting to negotiate with the assassin, the troops set fire to the barn. Booth covered his mouth and prepared to come out firing, but a young sergeant by the name of Boston Corbett, having crept up close to the barn, peered in through a chink and saw Booth getting ready. Drawing his pistol, he took aim through the chink and shot him.

Booth was carried, dying, from the barn and laid under a locust tree. He had been shot through the neck. As the sun rose over Garrett’s farm on the morning of April 26th, 1865, John Wilkes Booth breathed his last breath. The drama that had begun eleven days earlier with assassination of the president was at an end.

Three months later, David Herold, Mary Surratt and two more of Booth’s co-conspirators were hanged.

Abraham Lincoln, vilified through most of his presidency by friend and foe, attained in death a martyrdom that helped him become the most popular president in US history. It is ironic that the man who shot him had, throughout his life, enjoyed the honor and admiration of almost everyone who knew him, but in death acquired an ignominy so complete it tainted the lives of those who tried to help him. John Wilkes Booth achieved exactly the opposite of what he had intended. He cemented in glory the man he’d intended to destroy and plunged into disrepute a reputation he’d hoped would be raised in glory, his own.

John Wilkes Booth Escape Route Itinerary…

|

|

Mary Surratt’s Boarding House (Wok n’ Roll Restaurant)604 H Street NW |

|

Ford’s Theatre516 10th Street NW |

|

Surratt House Museum9118 Brandywine Rd. |

|

Dr. Samuel Mudd House and Museum3725 Dr. Samuel Mudd Road |

|

Rich HillBel Alton, MD |

|

The Pine ThicketBel Alton, MD |

|

HuckleberryFaulkner, MD |

|

Crossing The Potomac MarkerNewburg, MD |

|

CleydaelKing George County, VA |

|

Peyton HousePort Royal, VA |

|

Where Booth Died MarkerPort Royal, VA |

|

Garrett Farm SitePort Royal, VA |

Recommended Reading

Manhunt: The 12 Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer

Manhunt: The 12 Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer

by James Swanson

496 pages

February 6, 2007

My American Odyssey Route

Previous stop on the odyssey: Kitty Hawk, NC //

Next stop on the odyssey: Palmerton, PA

Other Tour Itineraries on My American Odyssey

| About the author: Malcolm Logan is a freelance writer who specializes in US travel and US history, designing driving tours, seeking out interesting destinations and exploring US adventure travel. He can be reached at malcolm.logan@rcn.com |

| Images: All pictures by Malcolm Logan, except John Wilkes Booth, Public Domain; Lincoln assassination illustration, Public Domain; David Herold, Public Domain; Cleydael, VirginiaPlantation; African American cabin, Public Domain; Garrett’s farm in 1865, Public Domain; The hanging of the conspirators, Public Domain |

3 comments

[…] stop on the odyssey: Waldorf, MD // Next stop on the odyssey: Pinkham Notch, […]

[…] Previous stop on the odyssey: Pigeon Forge, TN // Next stop on the odyssey: Waldorf, MD […]

Ride With the Assassin by Megan Hardgrave – a new historical fiction novel focusing on the Lincoln Assassination from a teenage witness perspective. The plot revolves around Mark, a boy who unwittingly helps John Wilkes Booth escape from Ford’s Theater after he assassinates President Lincoln. For 12 exciting days he travels with Booth along his escape route. It is inspired by a boy who held the reins of Booth’s horseon April 14, 1865.

The praise.

“Historical fiction enthusiasts will not be disappointed in Megan Hardgrave’s first children’s book, Ride With the Assassin. Language true to the Civil War Era and solid historical facts are encased in a beautifully crafted novel about a young man named Mark who unwittingly helps John Booth flee from the back door of the theater after shooting President Lincoln. The boy takes the reader through a first person account of events surrounding the assassination of President Lincoln and subsequent fury paced escape to avoid capture. Chaos surrounding theater events and discovery of John in the tobacco barn make the story nervously come to life. The reader will anxiously turn pages to an exciting climax. Ride With the Assassin is a story of being strong enough to make the right choices, growing up and learning from events in one’s life and realizing in the end that love and support of family conquers all.” Becky Brewer, Elementary School Librarian

“I thoroughly enjoyed it. First, I was very impressed with your story’s historical detail. Obviously, you put in a lot of research and it showed. I especially liked your descriptions of the Ford Theater and the events leading up to Lincoln’s death. Such details really enhanced the believability of the plot. Furthermore, I also liked the way you developed your characters. I particularly thought Mark and John Wilkes Booth were well thought out and described; your supporting characters were also quite strong.”

Jim Abrahams, well-known Hollywood director of Hot Shots!, Airplane!, and First Do No Harm; writer, Scary Movie 4

I wanted to make sure you received my comments on your wonderful book. As I said, with Lincoln’s wink at your leading man you had me. It was a fun read and gave just the right touch of period so it almost sounded like an old time memoir, I’d Say you should try for a film treatment. “Actor Patrick Gorman as General John Bell Hood in films”Gettysburg” and “Gods and Generals”

“Congratulations on your book. As a writer, in my case of screenplays, I empathize with fellow scribes. “, Ron Maxwell, director and writer films”Gettysburg” and “Gods and Generals”

Feedback:

“Ride With the Assassin is a great title for the book, and don’t change it.” A U.S. Navy Civilian Historian

· “Megan’s writing style is forthright.”

· “My daughters are excited about getting it.”

· “Love the historical story line.”

· “The book sounds wonderful, I’ll be ordering one tomorrow! And I am impressed with the plaudits you’ve already received for it. I’m looking forward to reading it.”

· “I started to watch a TV special on Booth’s escape and realized that by reading your book, I already knew it!”

· “This looks great! I’m going to use it in my middle school curriculum for 8thgraders next fall when we study the Civil War.”

· “I really loved it” 13 yr. old boy

“You wrote an very entertaining historic novel and being a retired writing teacher, I was impressed by all the excellent writing traits you used. Also I especially liked the timeline at the beginning .It was very helpful”

· “I don’t think I ever told you that I enjoyed the book and have passed along to my young history-loving grandson.”

“Read the book and really enjoyed it. You did great. Could not put it down once I started. Only comment is it might have been nice to somehow weave a little more background about the individual conspirators into the book somehow. Like your attention to detail and descriptions of things. Made them easy to picture. You are really talented.” Scott Skidmore

“”One sign of a well told story is the reader’s inability to stop until they know what happens at the end. Your ability to tell such a remarkable tale by meticulously intertwining accurate historical facts will not only leave readers fascinated but educated as well.”Ride With the Assassin” is a perfect introduction to the Lincoln Assassination story and will leave the reader only wanting to learn more.” Joe G, Booth Enthusiast

Sales have been over 350 copies sold since 2010 to the general public and 19 retailers.

Retailers that sell and carry this title:

DC Gift Shop.com, Washington D.C.

Cranston Historical Society ( the Govenor William Sprague Mansion), Cranston ,RI

Rock County Historical Society (Lincoln-Tallman House) Janesville ,WI

Stephenson County Museum, Freeport, IL

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Park , Hodgenville Kentucky

Ulysses S. Grant Cottage, NYC,

Lincoln Home National Historic Site/Bookstore, Springfield, IL (national park service)

The Appomattox Court House National Historic Park /Bookstore, Appomattox, VA (national park service)

The Denton Texas Public Library, TX

The National First Ladies’ Library, Canton, OH

Kentucky Historical Society 1792 Store, Lexington KY

Chester wood House, (home of sculptor Daniel Chester French of Lincoln Memorial fame) Stockbridge MA

The Huntington Bookstore, San Marino CA

Dr. Samuel A. Mudd House Museum, Waldorf MD

Civil War Pearce Museum –Navarro College-Corsicana TX

Reddick Mansion, Ottawa, IL

Hingham Historical Society, Hingham, MA

The Studebaker National Museum, South Bend, IN

The Surratt House Museum, Clinton, MD (on the John Wilkes Booth Escape Route)

How to order :

The book includes: Timeline, Escape Route Map, and Pictures, Size 5.5” x 8” Standard Paperback, perfect bound with glossy cover; approximately 120 pages.

Price: $18.48 each plus sales tax, for a total of $20.00, plus shipping and handling for Texas residents add $5.25. For east or west coast USPS shipping add $6.00

Make check or money order or websitewww.PayPal.com (Credit Card) send payments to:

Megan Hardgrave, 1846 E. Rosemeade Pkwy #297, Carrollton, Texas 75007. If you are a museum or other retail outlet, please e-mail megan_hardgrave@yahoo.com for wholesale pricing and quantity orders.

Megan Hardgrave,President

Collectible Profiles

1846 Rosemeade Pkwy #297

Carrollton,Tx 75007