The New Madrid earthquake was one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded on US soil. It coincided with one of the strangest murders in US history.

In the months following the murder there was scarcely an hour when the earth did not shake. The sound of it was like distant thunder, which gave way to cracks and explosions like muskets being fired. The smell of sulfur and brimstone hung over everything.

They said it was retribution from an angry god, punishment for the vile deed they had done. But if that was true, it put Isham and Lillburn at the center of everything, as if the whole world had been made to suffer for their transgression, like humanity deprived of paradise for Adam’s singular sin. Isham couldn’t believe it. He had never been that important.

He was the lesser of four sons born to Colonel Charles Lewis. His mother had been Lucy Jefferson, sister of President Thomas Jefferson. Alone among his brothers he had been denied the birthright of land, his father having squandered the family fortune before his turn came. He had written to his uncle the president and gotten a job at Natchez, but they had not treated him with the deference he felt he deserved, so he had abandoned his post and returned to Smithland where the thing happened that had set the earth to shaking, or so they said.

He saw Lillburn in a drunken rage, teeth clenched, face red, the cords standing out in his neck. He was howling with rage.

A World Gone Mad

He awoke to the sound of riflery and thought the world had gone mad again, but it was only the sound of nervous infantrymen firing into the fog. They would be reprimanded for that. General Jackson deplored waste and sought to keep their position secret, although everyone knew the British had marked them and would be advancing on them at dawn.

He nodded off to sleep and dreamed the dream that tormented him. He saw Lillburn in a drunken rage, teeth clenched, face red, the cords standing out in his neck. The slave George had broken the pitcher their dear departed mother had given them. George, that ne’er-do-well, sulky and impudent, stammering idiotically, trying to offer some excuse, but Lillburn knew it was deliberate, so he struck him, knocking him to the floor. Then everything went insane – in Isham’s dream, and in fact.

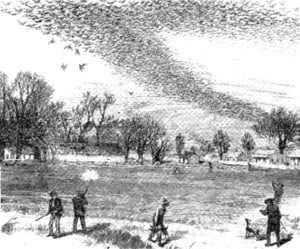

He saw the passenger pigeons exploding across the sky, thousands of them, blotting out the sun, their droppings falling like rain. He saw the squirrels descending the river bank like a flood, like a carpet of living creatures, squealing, frenzied, pouring into the river like a blooming slick of mud, drowning in their thousands. He saw the wild eyes of the panther among the reeds in the river bottom, the eyes of a demon, feral, crazed.

The world had gone insane and then Lillburn ordered George to be bound hand and foot – ordered the others to do it, jeered at them in their fear, told them he would teach them a lesson about running away and sulking and not obeying. They did it haltingly, reluctantly, and when Lillburn picked up the ax, they shrank back and begged. Slave George wept hysterically, pleading for his life, but Lillburn only sneered, a gleam in his eye like that of the panther. Then he raised the ax and brought it down with all his might.

A faint morning light invested the fog. When it cleared, the British would begin their advance. They would have to be ready to fight for all they were worth.

Optimism and Affliction

Isham woke with a start. A faint morning light invested the fog. When it cleared, the British would begin their advance. Isham and his fellow soldiers would have to be ready and fight for all they were worth, especially since the British outnumbered them at least two-to-one. But a good many were eager, confident of an American victory.

Isham recognized their optimism, a disease that afflicted his countrymen, a country that believed in providence, a conviction that they would prevail, a sense that every success was foreordained and every failure a mere setback. He had felt the same way too once, years ago, back in Virginia in the years after the Revolution when his family had had wealth, land and reputation, before his father lost it all, before they moved to Kentucky and everything came undone.

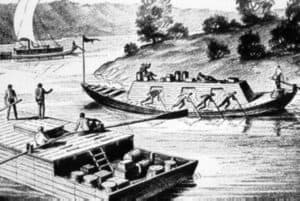

They had come down the Ohio River leaving out of Pittsburgh in 1807. The trouble began almost at once.

They had come down the Ohio River leaving out of Pittsburgh in 1807, having sold the Virginia land to pay off creditors, eager to make a new start. The trouble began almost at once. They had left too late and gotten delayed at the mouth of the Kentucky River due to ice. At the falls below Louisville they had to pay for a pilot out of their scarce resources yet nearly lost the boat in the rapids anyway. Then they had to travel 310 miles through a wild, dangerous country infested with hostile Indians.

Having arrived at last at the mouth of the Cumberland, at the town of Smithland, they found their new home a rough, shabby, disease-ridden place populated by a strange mix of frontier ruffians and stern Methodists neither of whom had much use for high born easterners like the Lewises. Within two years their mother had been carried off by illness, the whole family had been stricken by malaria, and Lillburn’s beloved wife Elizabeth had succumbed to disease and died.

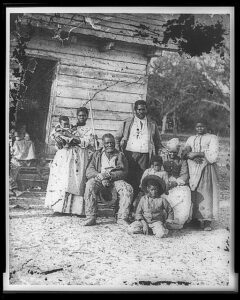

Lillburn did what he could to retain ownership of his slaves. The slaves and the land marked him as a man of wealth and influence.

Farming was difficult. The soil was good but birds and animals routinely devoured the crop. Money was tight. Lillburn borrowed profligately, buying medicine to stave off sickness, sending his daughters away to school, wheeling and dealing to hold onto the land, doing everything in his power to retain ownership of his fourteen slaves, for the slaves and the land were what set him apart, marked him as a man of wealth and influence, made him look better than he actually was.

But the slaves were mostly useless. They barely paid for their own upkeep. Unlike the slaves of the Deep South, Kentucky slaves rarely labored in the fields and were mostly servants, status symbols. To make matters worse, they were frequently indulged, treated like members of the family, and got it into their heads to malinger and talk back, and because Smithland lay across the river from Illinois, free territory, they some times ran away for days at a time, as if they had to answer to no one.

Slave George had run off, gone to Illinois to sulk for awhile over some perceived slight, and when he came back, Lillburn was furious, which was why he was on edge that night when they went down to the kitchen to get drunk, and why he had snapped when George broke the pitcher. But his reaction was out of all proportion to the crime.

Aftershock

Aghast at his brother’s horrific attack, Isham had reached out a hand to stay him but nearly got cut himself as his brother swept the ax back around like a woodsman and brought it down again and again on the groaning slave at his feet.

Blood splattered over all of them. The other slaves wept and moaned and begged for their lives.

Lillburn ordered them to take their knives and dismember the lifeless body. He stood over them supervising the enterprise and directing them to throw the severed limbs into the kitchen fire. Isham sat in the shadows watching in a sort of daze. Lillburn upbraided the slaves for their ineptitude and stupidity and warned them that this would be their own fate should they breathe a word of this to anyone, and then, all of a sudden, the earth shifted.

The ground jittered and convulsed. The logs cracked, the ceiling collapsed, and then the wall gave way, buckling inward.

The sound of it was terrifying, a thunderous boom that stretched out and seemed to grow louder. The logs of the structure shook and creaked. The ground jittered and convulsed. The walls cracked, the ceiling collapsed, and then the cabin gave way, buckling inward. The weight of it pulled the chimney over, spilling masonry, flaming logs and burning embers onto the ground before them, all mixed up with the charred limbs of the mutilated slave.

As soon as the shaking stopped they fled in abject terror. But the earth was not finished. The trembling went on, low, rumbling vibrations that continued for hours, relented, and then continued at intervals over days and weeks.

He instructed them to pick up the scattered body parts and seal them up behind the masonry. They did.

Two days later Lillburn gathered the slaves and told them they must rebuild the kitchen, beginning with the chimney. He instructed them to pick up the scattered body parts and seal them up behind the masonry, concealing his crime. They wept as they went about it. They were traumatized, as was Isham.

But Isham never questioned his brother. It was not his way to question his elders. People owed deference to those above them. He could never blame his brother for what he had done. Slave George had been insolent and rebellious and had paid for it with his life. There was nothing particularly remarkable about this. Back in Virginia a man could treat his slaves as he liked. The fact that there were those in western Kentucky who might consider what Lillburn had done murder registered only vaguely with him.

Two days after the chimney was rebuilt an aftershock tumbled it to the ground, spilling George’s body parts in the dirt.

And the matter might never have come up if it weren’t for the aftershock. Two days after the chimney had been rebuilt it tumbled to the ground, spilling George’s body parts in the dirt. A passing dog discovered the skull and carried it away to a place beside a public thoroughfare where it set about contentedly gnawing on it. A neighbor of Lillburn’s discovered the dog with its awful prize and reported it to the authorities. The skull still had enough flesh on it to identify it as that of Slave George. Lillburn was arrested.

The Vengeance of an Angry God

As the dawn came on, Isham mustered with the rest of his company and took up his position behind the barricades. He propped the barrel of his musket against the crossed timbers and waited. The British would be approaching from the south. They had landed below New Orleans near Lacoste’s Plantation. General Jackson had hurried down to meet them, and, after a brief skirmish, the British had withdrawn to regroup. Soon they would be back.

At an estimated 7.7 on the Richter scale the New Madrid earthquake was felt over 3 million square miles.

The fog was as thick as soup. No man could see more than 30 yards in front of him. The idea that the British might march in such conditions seemed inconceivable. Surely they would wait until the fog lifted. Isham relaxed and reflected on how he had come to be there.

Six weeks after the murder Lillburn was indicted. During all that time, scarcely an hour passed when the earth did not rumble. Mostly it was a low vibration like a menacing growl, but sometimes it grew more intense like a beast about to lunge.

The preachers claimed God was angry with the sinners, with all the swearing, fornication and double-dealing on the frontier. The Indians said it was because of the whites. Some even suggested it was because of slavery – came right out and said it. The nerve.

A passing dog discovered the skull and carried it away to a place beside a public thoroughfare where it set about contentedly gnawing on it.

Isham thought God was angry at the impertinence of man, at his lack of humility, at his pride. Men refused to bow down when they should have, when they should’ve known their place and abided. But everywhere there was impudence and unruliness, even among the women.

When he heard Letitia say she thought it was because of what Lillburn had done, he was surprised. Letitia was Lillburn’s second wife. She had always been a mouthy one, but this went beyond impudence. She should’ve been taken in hand, and he told Lillburn so. But Lillburn had always had a soft spot when it came to Letitia. He only sighed and shook his head. Even his wife was turning against him. Dejection was written all over him.

They released him on bond pending trial. Returning home, he tried to explain things to Letitia, but she shunned him. One day her people came and took her away, and Lillburn was left alone. It was then he formed his plan.

When he heard what Letitia had said he only bowed his head and sighed. Dejection was written all over him. He decided to end it.

Misfire

They would commit suicide together, he and Isham. There was no reason to go on. They were going to be convicted and hanged anyway, so they might as well take matters into their own hands. They were not men to sit idly by and let others take charge, they were Lewises, distant cousins of the great Meriwether Lewis who had explored all the way up the Missouri to Oregon, and nephews of President Thomas Jefferson. They were men of consequence, not playthings in the hands of backwoods lawyers and yokels.

They met in the graveyard where Lillburn’s first wife Elizabeth lay. They agreed to stand ten paces apart and aim the guns at each other. At a signal they would pull the triggers.

But Isham was not fully committed; he thought he might yet avoid the death penalty, after all he had not swung the ax, and men were not generally hanged for being accessories. He could simply refuse, but on second thought he could not make his brother, poor, long suffering Lillburn who had endured poor crops, insolent slaves, pig-headed creditors, a vindictive jury and an ungrateful wife, endure a disloyal brother as well. So he tried something else.

He said he was worried about a misfire. What if one of the guns misfired while the other went off? One of them would die and the other would survive. But Lillburn was not to be deterred. He explained that if the gun misfired the survivor could complete the act by shooting himself.

When Isham expressed confusion about how this might be accomplished when the muzzle was so far from the trigger, Lillburne told him to cut a branch from a tree, and he would show him. Propping the gun on the ground with the muzzle facing toward him, Lillburn bent over and placed the butt end of the branch against the trigger. “You do it like this,” he said. Then the gun went off. The top of Lillburn’s skull exploded. His body flopped over and sprawled on the ground, the gun resting between his thighs, still smoking.

The door was left open. If Isham had thought for a moment that it was an oversight he would not have slipped off.

Shocked, Isham stumbled back, hands to his face. He ran and got the authorities who for the most part believed his explanation about what had happened. They knew him well enough to know he would never have shot his brother. But they arrested him anyway, regretful that things had come to such as pass, yet concerned for the peace of mind of the community. So much bloodshed had been laid to the account of the Lewis brothers, and Smithland was already on edge from the aftershocks. Someone had to pay.

Jailbreak

As he waited in jail for his trial to begin, two things happened. First, Isham befriended his jailer Thomas Champion, who had known Lillburn and liked him, and second, the aftershocks stopped. Then one day Thomas Champion went off to collect some water and left the door open. If Isham thought for a moment Champion’s act was an oversight, he would not have run off and risked embarrassing him, but he took it as an invitation to put the whole ugly mess behind him, so he slipped out and made for the south.

Two weeks later he arrived in Natchez. He wasn’t there long. His creditors got wind of his presence and came looking for him, so he slipped out of town and headed to New Orleans.

When he arrived, the whole place was in an uproar. For more than two years the United States had been at war with the British—for the second time. On June 18th of 1812, the war had broken out, and for thirty months the tides of war had shifted back and forth. First the British gained the upper hand and then the Americans. Then, in late 1814, General Andrew Jackson, flush with victory over the British at Pensacola, marched his army west to reinforce New Orleans. Isham was there, trying to remain inconspicuous. Without a second thought, he enlisted.

When a fellow soldier pressed him, asking him if he wasn’t the nephew of Thomas Jefferson, he denied it.

Suspicion

They spent next 12 months building fortifications, and for the most part Isham kept to himself and didn’t socialize. But one day something happened that reminded him of the injustice of the world he inhabited. A fellow soldier recognized him and asked him if he wasn’t the same Isham Lewis who had been involved in that ugly business in Kentucky. Isham denied it. When the soldier pressed him, asking him if he wasn’t indeed the nephew of Thomas Jefferson, he scoffed declaring that if he was the nephew of Thomas Jefferson he wouldn’t be lying here in the mud with a bunch of ignorant farm boys, would he?

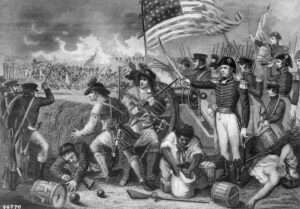

The order rang out. “Fire!” And the Americans poured musket fire and grapeshot into the confused British.

The soldier guessed that was probably true, but he seemed suspicious anyway, and, when he was gone, Isham brooded over his sorry circumstances and rued the blithe optimism of the soldiers around him. They thought they were going to win the battle and defeat the British. To a man they believed they were going to prevail. They thought the hand of providence was upon them. Only he knew better. They were outnumbered. The British were better trained and better armed. Justice and merit had nothing to do with it. The world was unkind. They were going to be defeated.

Emerging from the Fog

The Battle of New Orleans was a surprising victory. Although they outnumbered the Americans, the British suffered ten times as many casualties and lost.

On the morning of January 8th, 1815, the fog began to lift. The soldier next to Isham on the parapet nudged him and pointed. Isham sat up and looked. He could hardly believe his eyes. As the fog lifted he could make out vague forms moving toward them through the haze, marching toward them in long straggly lines. The soldiers manning the parapet looked at each other and grinned. They raised their guns and awaited the order.

The British kept coming, closer and closer, unaware of what awaited them less than a hundred yards ahead. The order rang out. “Fire!” And the Americans poured musket fire and grapeshot into the enemy. The British fell by the dozens. The survivors panicked and fled. The Americans kept shooting.

When it was over, the British had suffered 291 killed and 1,267 wounded. The Americans by comparison had suffered only 13 dead and 39 wounded. It was a miracle.

When it was over, the British had suffered 291 killed and 1,267 wounded. The Americans by comparison had suffered only 13 dead and 39 wounded. It was a miracle.

Among the dead was counted one Isham Lewis, or at least that was what was reported in the official census. But the counting of the casualties at the Battle of New Orleans was attended by a great deal of confusion because, in the course of things, rumors had spread that the war was over, and as a result many of the soldiers left their companies and went home.

Among those who walked away was a man somewhat older than the rest, a man with deep lines in his face and a weary, jaded look, a man struggling with the meaning of his purpose in this world, a man confused by justice, merit and fate, a man with no name.

Author’s note:

This is a work of fiction based on historical events and real people. Isham Lewis was indeed listed among the casualties at the Battle of New Orleans, yet some room still exists to speculate that this was a ruse by a fugitive to deceive his pursuers.

The events surrounding the murder of Slave George in 1811 by Lillburn Lewis in the company of Isham Lewis, as well as Lillburn’s subsequent suicide, have been thoroughly researched and recorded by Boynton Merrill, Jr. in his excellent book Jefferson’s Nephews: A Frontier Tragedy. However, the motivations of the killers, their attitudes, opinions and reactions are purely speculative.

The New Madrid Earthquake of 1811 was one the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded on US soil estimated at a magnitude 7.7 on the Richter scale. With its epicenter in the Missouri boot heel, it was felt strongly over 50,000 square miles and moderately across 3 million square miles. Smithland, KY where these events took place was 85 miles from the epicenter.

Previous stop on the odyssey: Chicago, IL //

Next stop on the odyssey: Miami Beach, FL

Image Credits:

Earthquake fissure 19th century, Public domain; Rage, Ana Rodriguez Avila; Passenger pigeons, Public domain; Fog, Holger Froese; Flatboat and Keelboat on the Ohio River, Public domain; Slave family, Public domain; Ax Murderer, VilliscaMovie.com; Cabin in an earthquake, Public domain; Chimney bricks, Simon Bisson; Collapsed chimney, Dogssaloon; San Francisco earthquake, Public domain; Despair, Ana Rodriguez Avila; Dog gnawing a bone, Lonnie Dunn; Dead man’s boot, Dave 77459; Jail door, Reivax; Isham’s travels, Malcolm Logan; Muskets, Matt Smeltzer; Suspicious soldier, One lucky guy; Battle of New Orleans, Public domain; Walking away, Jim Crossley