In the bayous south and west of New Orleans the fallout from the BP oil spill continues to be felt more than a year after the well was capped.

Shrimp boats sit idle, not because the fisheries are producing seafood that is unsafe to eat – Gulf Coast seafood was deemed safe for consumption months ago1 – but because squeamish outsiders remain suspicious.

Offshore oil rigs are being towed away to distant waters, drying up thousands of potential jobs here, not because drilling remains under moratorium – the post spill moratorium was lifted in October of 2010 – but because the federal government is slow to grant permits. Tourism is in peril. While New Orleans has clawed its way back, the swamp tours, fish camps, culinary trails and plantation tours of this region are hanging by a thread.

The common denominator seems to be mistrust, which makes the battered economy of southern Louisiana a microcosm of the larger US economy whose single biggest drag is the unwillingness on the part of anyone – consumers, businesses or government – to take a risk.

Like the country as a whole, this region has been burned twice: first by the recklessness of an under-regulated industry, and then again by the fear engendered by what happened as a result.

The good people of Acadiana desperately need someone to take a gamble on their behalf. Yet outsiders remain wary.

Fear Not, Cajun Country is Calling

Known as Acadiana, because of the prevalence of Cajun peoples in the area (the word Cajun is an idiomatic rendering of the word “Acadian”), this low lying region is the largest provider of domestic seafood in the continental US2 and produces more than a quarter of its domestic oil 3. The two industries had co-existed amicably for years until the events of April 20th, 2010.

Known as Acadiana, because of the prevalence of Cajun peoples in the area (the word Cajun is an idiomatic rendering of the word “Acadian”), this low lying region is the largest provider of domestic seafood in the continental US2 and produces more than a quarter of its domestic oil 3. The two industries had co-existed amicably for years until the events of April 20th, 2010.

The BP oil spill dumped 155 million gallons of crude oil into the Gulf, fouling the waters and killing tens of thousands of birds and marine life, as well as forcing fishery closures across more than 88,000 square miles 4. Thousands of fishermen lost their jobs.

BP responded with payouts designed to compensate victims for losses traceable to the spill, but such generosity has done little to allay the long term effects of a crippled economy. A rebound in tourism is fervently hoped for but long in coming.

To visit Acadiana now can feel a little like an act of charity. But if so, it’s an act of kindness that can pay dividends in more ways than one. The region is rich with culture and history. And then there’s the food. If you want to get a taste of Louisiana, you must get a taste of the region.

The Tabasco Factory Tour and Other Culinary Look-Sees

At the Conrad Rice Company in New Iberia, a $4 tour of a working rice mill begins with a fifteen minute film on the culture of Cajun country, followed by a guided tour of the 100 year old mill by one of the friendly ladies who runs the company store. The mill is a rustic wooden building employing 22 people and an indolent cat that cannot be persuaded to move from its perch atop a conveyor belt by any other means than switching it on.

At the Conrad Rice Company in New Iberia, a $4 tour of a working rice mill begins with a fifteen minute film on the culture of Cajun country, followed by a guided tour of the 100 year old mill by one of the friendly ladies who runs the company store. The mill is a rustic wooden building employing 22 people and an indolent cat that cannot be persuaded to move from its perch atop a conveyor belt by any other means than switching it on.

In the course of the 20 minute walk-through you learn how rice is processed, an interesting procedure, and then your guide answers questions and concludes by offering samples, with red beans and hot sauce, of course, in the adjacent store.

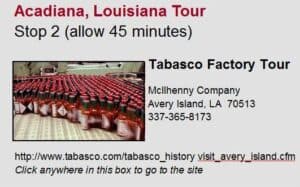

Not surprisingly, the hot sauce they provide is Tabasco, and after you’ve wrapped up your quick tour of the mill, it’s a short ten minute drive to Avery Island where the Tabasco factory tour awaits.

700,000 bottles of Tabasco are bottled here every day. Some of the red peppers used in making it are grown on the surrounding acreage. Tabasco was founded by Edmund McIlhenny in 1868 and is still made with hands-on care by the McIlhenny family. The word “tabasco” means “hot and humid” in the Aztec language. It’s an apt name for the spicy condiment, a simple mix of aged red peppers and all natural high grade vinegar.

The Tabasco factory tour is brief and tilts toward self-promotion. You begin in a two room exhibit gallery where a guide meets you and says a few words before showing you into a theater where a 10 minute film functions mostly as an advertisement. Then you are shown into a fifty foot glass walled corridor where you are free to gawk at factory workers sitting at their machines before being let  into another small exhibit hall.

into another small exhibit hall.

Afterwards, you can tour the neighboring Jungle Gardens for an $8 fee and wander amidst centuries old oaks draped in Spanish moss or visit the gift shop, housed in a large wooden cabin near the factory.

The dining patio in front of the gift shop is the liveliest place in the whole arrangement. You may be tempted to tuck into another bowl of red beans and rice while listening to the piped-in Cajun music, but hold your palate. Greater delights await.

Morgan City: Dining with Family at Rita Maes

Rice and Tabasco are common ingredients in Cajun cooking. When you add shrimp, you are most of the way to a good jambalaya, the signature dish of  southern Louisiana. Step through the door of Rita Mae’s Kitchen in Morgan City and you’ll get the rest of the way there.

southern Louisiana. Step through the door of Rita Mae’s Kitchen in Morgan City and you’ll get the rest of the way there.

The jambalaya at Rita Maes combines shrimp and andouille sausage with the holy trinity of celery, pepper and onions to conjure an authentic dish that’s hard to beat. Rita Maes is located in a modest residential home on a quiet tree-lined street. Dining there makes you feels like you are dining with family. They specialize in crawfish etouffe, shrimp po boys and red beans and rice. It’s a great stop for lunch.

Afterwards, you might like to visit a shrimp processing facility. But no such luck. Many shrimp processing facilities are now closed and up for sale, victims of the spill.

Virgil points to Morgan City from the deck of the “Mr. Charlie” offshore oil rig. His take on the economic impact of the spill was fascinating.

The “Mr. Charlie” Authentic Offshore Oil Rig Tour

Ironically, BP still sponsors a website touting the safety and variety of Gulf Coast cuisine and implies that tours of shrimp processing facilities are still available, but the links no longer work. What BP doesn’t promote is another tour in the region, one of a decidedly different nature and one you must see if you want to understand what happened here.

The tour of the authentic off shore oil rig called the “Mr. Charlie” is an opportunity for the oil industry to make its case. The tour is run by an outfit called The International Petroleum Museum, although as far as I could tell there is no actual museum and finding the place is something of a chore as the sign blew down in a storm and no one ever bothered to replace it. Nevertheless, it is one of the most eye-opening attractions in Acadiana.

I was fortunate to have the full attention of my tour guide, a sincere advocate for the oil industry named Virgil. When Virgil is not conducting tours he is assisting in training wanna-be rig workers. Oil companies send apprentice roustabouts to the Mr. Charlie to spend a couple of weeks living and working here, anchored a few feet off shore, before sending them out to sea. Here they receive hands-on training to see if they can endure the isolation and rigorous 12 hour workdays required on an offshore oil rig.

The Mr. Charlie is a working rig that once did duty in the gulf before being towed to this place on Berwick Bay in Morgan City. Aboard, you can see the sleeping quarters, rec room and mess hall of the 70 or so workers that typically inhabit an offshore rig like this. Then you go up top where the cables, pipes and cranes are used to drill and pump wells, and you learn how the whole thing works.

It’s a fascinating glimpse into the science and engineering of drilling and if you want to talk spill with Virgil he is more than happy to oblige.

It’s a fascinating glimpse into the science and engineering of drilling and if you want to talk spill with Virgil he is more than happy to oblige.

Please Don’t Call it Fossil Fuel

Virgil blames the government for the economic woes of the region, contending that misguided government policies and over-regulation stifled job growth and pushed up the cost of oil. He acknowledges that the spill was a tragic mishap but that spills are a common part of drilling and that even if man-made spills never occurred, oil would seep up naturally from the ocean floor.

Long ribbon-like bridges span the marshland leading out to Grande Isle. You are 95 miles south of New Orleans here. Click any picture to enlarge.

Virgil claims that peak oil is a myth, and that we are nowhere near running out of oil in the United States. He asserts the government is deliberately holding us back, and that government subsidies for alternative energy are a mean-spirited attempt on the part of legislators to hobble the industry’s growth. He insists that vast untapped oil reserves exist within our borders, that the industry only needs to be unshackled from government regulation to find them, and that, if permitted to do so, job growth and energy independence would naturally follow.

Our conversation takes a most interesting turn when Virgil claims that scientists don’t actually know what oil is, that the theory that oil is actually the remains of long dead marine life is probably wrong, and that politicians who insist on referring to it as fossil fuel are trying to discourage drilling.

“Geologists keep telling us we’ve reached the maximum depth at which we can expect to find oil but when we drill deeper we find more. That suggests they’re wrong about it being the remains of marine life.”

“Or,” I suggest, “It could be that they’re wrong about how long life has existed on the planet.”

At this, Virgil shrugs. “I’m a Christian and I believe God made the planet. I don’t get too worked up about millions of years this way or that. I believe God will provide.”

Later, he hands me his card. On the back are written the words: “In the beginning God created… energy.”

Bayou Lafourche and Those Who Always Pay

Fishing boats line the wharves at Golden Meadow at sunset. This region is the largest provider of continental seafood in the United States.

Whether or not the true source of Acadiana’s miseries is too much regulation or too little, the fact remains: the economic engines of the region have ground to a halt. Nowhere is this more evident than along Bayou Lafourche between the towns of Lockport and Golden Meadow where idle fishing boats line the wharves.

When I stop to take a picture of a lovely little boat, a stockily built, deeply tanned man approaches and asks me what I’m doing. He’s not unfriendly, just curious.

I tell him I find the boat picturesque, and he looks at it endearingly, as if seeing it for the first time. I get the distinct sense that he’s about to ask me if I want to buy it. His name is Phillip and he tells me that he has been shrimping for 25 years. Since the spill he’s only been able to find work by helping out with oil mitigation.

As a result of the damage done to his livelihood by the spill, he’s supposed to be getting pay outs from BP on an interim basis, retaining his right to sue, but BP has been dragging their feet, he says. He had the option to accept a quick pay out of $5,000, which he would have gotten right away, but he turned it down because accepting it would have required him to waive his right to sue, and he is not sure yet how badly he’s been hurt. 5 He knows others who have, out of desperation, gone for the quick pay. He had been considering doing so himself, but $5,000 doesn’t go very far and he has no confidence he can pull up stakes and find work elsewhere.

I ask him if he thinks Gulf Coast seafood is safe to eat. He tells me the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) has done  exhaustive studies on Gulf Coast seafood and has not encountered even one incident of contaminated fish making it to market. 6 Still the perception persists. “BP did this to us,” he says. “They should pay, even if it puts them out of business.” Then he hangs his head. “That’s not gonna happen,” he says. “Instead, it’s people like me who’ll have to pay.”

exhaustive studies on Gulf Coast seafood and has not encountered even one incident of contaminated fish making it to market. 6 Still the perception persists. “BP did this to us,” he says. “They should pay, even if it puts them out of business.” Then he hangs his head. “That’s not gonna happen,” he says. “Instead, it’s people like me who’ll have to pay.”

Not even one case of tainted seafood? Really? So are these waters actually safe?

Grande Isle and Another Kind of Menace

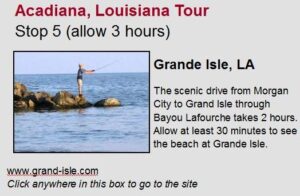

I head down to Grande Isle, the furthest point south on the Louisiana Gulf Coast, to see what the water looks like down there. Long ribbon-like bridges lead out over the estuaries punctuated by islands bristling with tall grass. Every time I think I’ve reached the final outpost another bridge carries me further out. After about 45 minutes, I finally reach Grande Isle. I am 95 miles south of New Orleans.

Grande Isle is a haven for fishermen. It is lined with brightly colored summer cottages on stilts. Back in May of 2010 its beaches were covered with tar balls. Today the water appears clear. A yellow daisy rolls in the surf and washes up at my feet untainted.

The bridges are crowded with fishermen. A few families are relaxing on the beach. Out on the breakwater an angler is casting. But no one is  actually swimming. On closer inspection the reason becomes clear. The water is infested with jellyfish.

actually swimming. On closer inspection the reason becomes clear. The water is infested with jellyfish.

Jellyfish blooms occur as a result of ocean currents, nutrients, and oxygen concentration. A sudden increase in the jellyfish population happens when fish occupying the same ecological niche have been killed off. As I turn to go, I notice a dead fish rotting on the beach.

Let’s be clear. Things are not pristine here. But no other sign of contamination troubles my eye, and all those fishermen are keeping their catch. If they are brave enough to eat it, what am I afraid of?

Thibodaux: Sophisticated Cajun Cuisine at Fremin’s

Cajuns know how to have a good time. They have their own style of music and dancing and they welcome all.

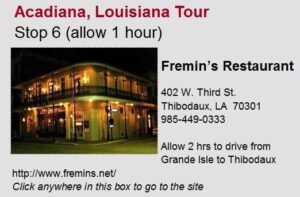

Back up the road in Thibodaux, Louisiana I order the charred oysters at Fremin’s. Fremin’s is located in a historic 19th century building with a wrap-around wrought iron balcony and French doors, exactly the kind of thing you would find in the French Quarter. The building has been restored to its original design and features porcelain tiles, pressed tin ceilings, long leaf pine floors and a mahogany bar.

My oysters are basted with Italian herb sauce and freshly grated Parmesan. I accompany them with a tasty seafood gumbo and a Cobb salad including lump crab meat. I wash it all down with an Abita, Louisiana’s premier beer. As I dine, a live jazz combo plays. It is a relaxing and sophisticated atmosphere with a wonderful 19th century ambiance. Well worth the price.

That’s one of the great things about southern Louisiana. Here you can enjoy a rich cultural tradition and world class cuisine at bargain prices – if you can only overcome your misgivings.

The internet is still riddled with warnings about Gulf Coast seafood. But most of it is more than a year old. The newer postings share the opinion of folks down here, that the seafood is safe to eat now, yet people are still leery.

Houma: Cajun Music and Dancing at the Jolly Inn

One saving grace for the people of this region is their joie de vivre. When life gets them down they know how to perk up. At the Jolly Inn in Houma live Cajun music gets the locals moving every Friday night from 8pm-11pm. When I arrive, couples of all ages are spinning and stepping to the sounds of an accordion and washboard. There are plenty of smiles. The plywood walls and

A shrimper’s boat at Bayou Lafourche. Not even one case of tainted seafood making it to market has been reported.

gingham patterned tablecloths make the place feel like an old swamp shack.

I stand off to one side tapping my foot, drinking beer. Eventually one of the band members approaches and asks if I would like to have a go at the washboard. Before I know it, I’m part of the band and it feels good.

Acadiana is a friendly and generous place. The people are hardworking and decent. They have suffered undue hardship, first with Katrina, and then with the oil spill. Many of them are hanging on for dear life. They need tourists to come and partake of all they have to offer: great food, interesting attractions, wonderful music, beautiful scenery, and a rich and unique history.

A year after the spill, visiting here can feel at little like an act of charity. But charity implies a sacrifice, and it is no sacrifice to visit Acadiana. On the contrary, it’s a pleasure.

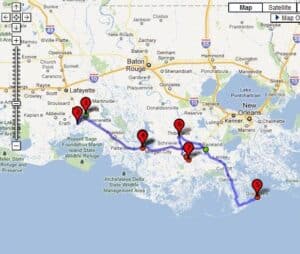

Interactive Acadiana Tour Map

Click the map for more detail

View the Complete Photo Album: Acadiana After the Oil Spill on Flickr

Next stop on the odyssey: Washington, DC

Sources:

1 Werner, Erica. “Obama Declares Seafood Safe to Eat.” War on You: Breaking Alternative News. 14 June 2011. 29 Sept 2011.

2 Kinsman, Kat and Latrent, Sarah. “Gulf Coast Chefs, Fishermen Fight Tide of Misinformation.” CNNLiving. 25 May 2010. 28 Sept 2011.

3 “Energy Security.” Mary Landreau, U.S. Senator for Louisiana. 2011. 28 Sept 2011.

4 “A Deadly Toll: The Gulf Oil Spill and the Unfolding Environmental Disaster.” Center for Biological Diversity Report. April 2011. 29 Sept 2011.

5 Canfield, Sabrina. “Fight Intensifies Over BP Claims Process.” Courthouse News. 16 August 2011. 29 Sept 2011.

6 Towey, Megan. “Is Gulf Coast Seafood Safe Enough to Eat?” Couric & Company, CBS News. 18 April, 20ll

Image Credits

Yellow daisy, Malcolm Logan; New Orleans trolley, Malcolm Logan; Jean Pritchard at Conrad Rice Mill, Malcolm Logan; Cat on conveyer, Malcolm Logan; Tabasco bottles, Shane K. Bernard; Snowy Egret, Malcolm Logan; Rita Mae’s, Malcolm Logan; Oil rig, Malcolm Logan; Virgil on the rig, Malcolm Logan; Oil Clean Up, Public Domain; Angler on the rocks, Malcolm Logan; Bayou bridge, Malcolm Logan; Grande Isle Vacation Homes, Malcolm Logan; Fishing boats at Golden Meadow, Malcolm Logan; Sunset on the marshlands, Malcolm Logan; Fremin’s, Malcolm Logan; Jazz combo, Malcolm Logan; Cajun Musician Jo-El Sonnier, David Simpson; Cajun dancing, The Jolly Inn; The swamplands, Malcolm Logan; Shrimper’s boat, Malcolm Logan

3 comments

[…] more about the attractions of Cajun country at My American Odyssey.com, Share Posted in Cooking « Meaning Of Yoga Useful Tips To Find Best Cooking Programs […]

[…] stop on the odyssey: Acadiana, LA // Next stop on the odyssey: […]

[…] Jefferson Parish, LA Of Shrimp and Petroleum: One Year After the Oil Spill […]