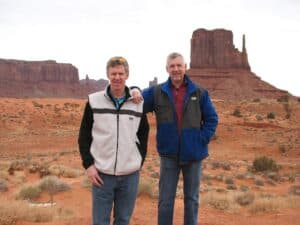

Monument Valley, a place iconic for its association with the American west is also a repository of cultures.

As a child he witnessed magic. Among the spires of orange and russet rock, in the shadows of parapets ribboned with plum colored bands left by long receded seas, he watched as the Hopi medicine man placed the tip of an eagle feather against his mother’s neck and sang. His mother had insisted on the Hopi medicine man, although they were Navajos themselves. She knew that the Hopis had healing powers inherited from the Ancient Ones, the ones who had built the cave dwellings and left the petroglyphs, mysterious powers to cure and revive, to hunt down evil spirits and draw them out.

The medicine man peered down the shaft of the feather, muttering strange words, a song. He raised a piece of quartz, positioned it between his eye and the feather and moved the feather around on his mother’s neck until he found the spot, and then he set it aside and leaned over and put his mouth there and sucked. He pulled it out and spat it on the ground, a viscous glob of blood colored phlegm. And, with that, the tremors left, all the symptoms were gone. Even after the doctors in Flagstaff had told her it was impossible that she would ever recover from the stroke, the Hopi medicine man drew it out.

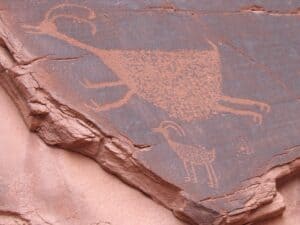

Don explains the significance of the spiral in Anasazi culture. Soon we would see this symbol in wall paintings on the rocks of Monument Valley.

He told us this while we were sitting in the pick up truck beside serrated ramparts of reddish brown shale and siltstone, and then we got out and he showed us the drawings. A fish, a rattlesnake and a pronghorn antelope, etched on the wall, put there at least 700 years ago by the Ancient Ones, the ones who had disappeared. Nobody knew where they went. Suddenly about the year 1200 A.D. they just vanished, leaving behind an advanced civilization of stone and earth dwellings, well built roads, elaborately designed pottery, organized religion, good medicine. The ruins of their ancient cities could still be seen at Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon but they had been here too, in Monument Valley.

Hidden in Patterns

His name was Don Mose and he was a Navajo writer, educator and storyteller. Intrigued by the mysticism of his ancestors, he delved into the origins of Navajo culture and discovered a rich world. Navajo weaving designs, those colorful geometric triangles and squares are something more, as he discovered, a perfect demonstration of Cartesian mathematics, the foundation of calculus. Hidden in those patterns is an equation, a formula, perhaps the solution to something.

He wrote a book, he made a film, and he came to the attention of the Russians who had a native people of their own, way out on the Siberian plains. They invited Don to come and speak to them. He flew to Moscow and then to Tolmachevo and drove out into those hinterlands and spoke through an interpreter. When he was done a woman came up to him and said, “I think I understood what you were saying.” They compared words. The word for sky “Yaoilhil” was very similar. The word for sweet “likhan” almost identical. There were many words like that.

In Navajo lore they tell of a great journey across an icy waste. In the lore of indigenous Siberians there is a tale of a great journey back and forth. The Navajo’s tell of a group of people left behind. They call them, “the ones who went through the cold”, which in Navajo is pronounced “A-Laska”.

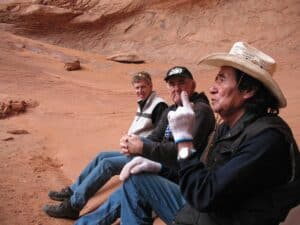

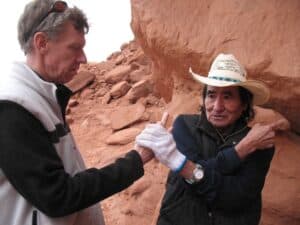

Using my brother’s hand, Don explains the significance of the hand prints left on the rocks by the vanished people of this region centuries ago.

Don has been to Alaska and visited the Athabascan people. The similarities between the Athabascan language and the Navajo has been noted by anthropologists. While he was there, they took him to a glacier and showed him the caldera of a volcano that had erupted centuries before. They told him that a group of people had once lived at the base of the volcano but had left.They had traveled south and were never seen or heard from again.

The Evolution of a People

The Zuni people of the American southwest called the newcomers apachu, meaning “strangers”. It was about 1,400 A.D. when the apachu migrated into the region from the north.

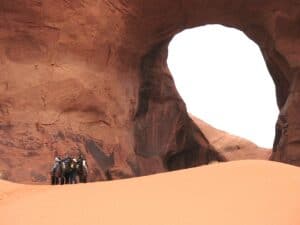

A trio of riders wait before the Ear of the Wind, a round opening in a wall at the top of a picturesque dune.

They were an adaptable people. Hunter-gatherers at first, they adopted the settled agriculture of the Zuni. Or at least some of them did. One group preferred hunting and raiding, so they split off and formed their own tribe. Those apachu became the Apaches. The ones that remained behind wore a name given to them by the Spaniards. They were called the Apaches de las Nabahu, meaning “the Apaches of the Cultivated Fields”. Over time that got shortened to Nabahu, and then when the Americans came along, bastardized into Navajo.

Cultures evolve when they adapt and assimilate, and when they have the strength to leave behind that which is untenable. There is much debate about what happened to the Anasazi, the Ancient Ones. One story has it that they were wiped out by a drought. Another postulates that internecine warfare did them in.

The most plausible scenario has them leaving the region in the face of those calamities, migrating south into Mexico and being absorbed into other tribes. In any case, between 1,400 and 1,500 A.D. the Navajo moved into the former homeland of the Anasazi and are still there today.

The Navajos were themselves a people with a long history of leaving untenable situations behind. Although scientists have not conclusively confirmed it, their migratory journey is well understood by people like Don Mose. He knows that they migrated from Siberia to Alaska to the desert southwest, and that they evolved from hunter-gatherers into farmers and then into herdsmen as the Spanish introduced them to animal husbandry.

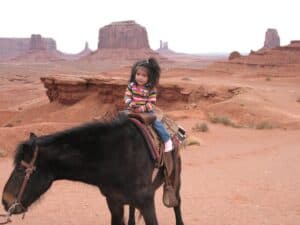

He knows that they are still evolving today becoming businessmen and entrepreneurs, utilizing their assets for profitability, among which is one of the most stunning tourist destinations in North America, a place iconic for its association with the American west, Monument Valley.

Mesas, Buttes and Spires

You don’t have to be too cynical to take note of the fact that this land still belongs to the Navajo, that it has not been ripped away by the federal government on some flimsy pretext in violation of a treaty. As a result, when you visit Monument Valley today you are not ushered around on well paved roads in air conditioned buses. The place is a little rough around the edges.

He asked us to lie back and observe where the edge of the rock was cut out against the sky, forming the shape of an eagle.

You can tour parts of Monument Valley on your own but unless you have a four-wheel drive with a high carriage you will find yourself struggling. The roads are cratered and crumbling and give way to dirt tracks. Having a guide is the way to go, not only because they know the 17 miles of roads here and how to navigate them, but because they are Navajos and can add depth and color to what you are seeing. For this is not just a collection of unusual rock formations. It’s a repository of cultures.

Our tour guide Don Mose took us first to a Navajo hogan, a traditional dwelling made of mud, rounded like an igloo, and supported inside by cedar logs. He grew up in one of these and was initiated into manhood in a sweat lodge like the one nearby. Today he lives in a house.

After the hogan, he drove us deep into the Tribal Park, which is the heart of Monument Valley, instantly recognizable from countless appearances in Hollywood movies. He took us to John Ford Point where the legendary film director made ten films, including the classics Stagecoach and The Searchers.

Other movies made at Monument Valley include Easy Rider, 2001, A Space Odyssey, Once Upon a Time in the West, Back to the Future II, Forrest Gump, and The Lone Ranger. Today the Navajos exact a fee from the leasing of their land for film making. It’s another way they are evolving.

Spirals, antelopes and snakes. What were the Ancient Ones trying to tell us? Don Mose has some ideas.

Inspiring Art

Don drove us out onto the Scenic Valley Road. This part of the park is off limits to the public and can only be accessed by authorized guides. This keeps the riff raff out and safeguards the rocks against graffiti and vandalism. From here you can see for miles across the valley to the widely scattered mesas, buttes and spires, reddish orange in the midday sun.

These rocks were formed by wind and sea erosion over millions of years, resulting in a variety of curious formations. The so called Two Mittens are the most recognizable, looking like two enormous hands facing each other, and then there’s the Sun’s Eye, an elliptical hole eroded in a cathedral ceiling of overhanging sandstone, and the Ear of the Wind, a round opening in a wall at the top of a picturesque dune. These are places that inspire art.

In this video Don tells the story of his trips to Siberia and Alaska in search of the origins of the Navajo people.

At each of these places Don stopped and told us a story. He told us how his mother used the power of the Ancient Ones to find his grandfather’s lost wallet. He told us how the Hopi Medicine Man healed his mother with an eagle feather and a quartz. He told us of the spiritual meaning of the hand prints left by the Ancient Ones on the rocks. And he told us of his journey of discovery to Siberia and Alaska.

At the Big Hogan formation, a large natural amphitheater in the shape of a hogan (as the name implies), he asked us to lie back and observe where the edge of the rock was cut out against the sky, and in that outline he showed us the shape of an eagle. In Native-American cultures the eagle is a messenger that carriers the prayers of human beings to the spirit world. Then he asked us to think of someone who was hurting, someone in physical or spiritual pain, and, as we did so, he sang a Navajo healing song to the eagle in the rock.

Good Medicine

In the end he brought us back along the rutted and crumbling road in his old pick up truck to the place where we had started and said goodbye. It was like saying goodbye to an old friend, for in the few hours we’d spent together we had learned so much about him and his people, about their origins and history, about their poetry and faith, and about their long spiritual journey.

I suppose we could’ve toured Monument Valley on our own, but if we had, we would have seen a lot of interesting rocks. As it was, we got some insights into the cultural survival of a people, a taste of Navajo magic, and a dose of good medicine.

Check it out…

Navajo Spirit Tours

Navajo Spirit Tours

P.O. Box 360324

Monument Valley, UT 84536

(435) 727-3403

Previous stop on the odyssey: Telluride, CO //

Next stop on the odyssey: Las Vegas, NV

Image credits:

All images by Malcolm Logan