The tribes had begun to embrace a new religion, a mystical dance that revealed strange visions of a future world, one that would be kind and generous to the beleaguered Sioux.

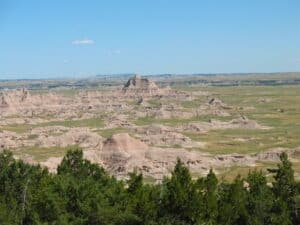

At the South Unit of Badlands National Park in South Dakota there’s a visitor center that doesn’t really want visitors. The South Unit is a haunting landscape of fantastically eroded buttes, pinnacles and spires. Together with its deep draws, high tables and rolling prairies, it is one of the most visually stunning landscapes in America. Yet the area has few roads or trails and is accessed primarily by dirt tracks, impassable in wet weather. If you want to hike there you are advised to notify the White River Visitor Center.

The Visitor Center is a trailer with a teepee in front. It may or may not be open. If you’re lucky enough to speak to someone, you’ll be informed that local landowners in the area can get crotchety and may refuse permission to cross their lands. Under some interpretations of the Castle Doctrine this may mean you could get shot.

A visit to the White River Visitor Center at Badlands National Park may not strike you as warm and fuzzy.

If that’s not enough to dissuade you, you’ll be told to watch out for unexploded ordinance in the area. In some places the ground is littered with shell casings and unexploded bombs. Unlike the Ben Reifel Visitor Center, which welcomes a great many satisfied tourists to the North Unit of the Badlands National Park, a visit to the White River Visitor Center doesn’t exactly feel warm and fuzzy. The South Unit feels like it’s off limits to tourists, although technically it’s not.

Once this area went by a different name. It was called The Stronghold. According to Merriam-Webster, a stronghold is a place of security or survival, a place dominated by a particular group or people. Strongholds are not supposed to be violated, not without consequence.

The Badlands are a haunting landscape of fantastically eroded buttes, pinnacles and spires. (Click any picture to enlarge.)

How to Dispossess a People

In 1942 the United States government capped 71 years of blatant land theft by taking possession of 341,000 acres of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, home of the Ogallala Lakota Sioux. Then turned it into an army gunnery range.

Prior to that, the land had been guaranteed to the Sioux after the lands guaranteed to them in the 1868 Treaty of Ft. Laramie were carved up, reduced and partitioned into five smaller reservations. The land guaranteed to them in 1868 had been granted to them after they had been pushed off their ancestral lands, which comprised large portions Wyoming, Nebraska and the eastern Dakotas. They had come to those regions from Minnesota where they had been pushed off their land in the 1850’s.

Two hikers descend the Saddle Pass Trail in Badlands National Park. This is harsh country, but stunning.

In 1942 when the War Department confiscated the land, they gave the Sioux 40 days to get out with the threat that bombs would start falling whether they were there or not. The Sioux got out. As had occurred in previous dispossessions, the Sioux were promised fair compensation for their land, but accounts vary as to how much they got, if anything at all. There the matter stood until 1958.

In that year the army began winding down the Badlands Bombing Range. Before the decade was over, the military had declared the land “excess”, meaning it was extra land they didn’t need and didn’t know what to do with.

Naturally, the Lakota Sioux lobbied for the return of their land, and in 1968 the land was transferred to the Interior Department and offered to the Sioux for repurchase. But the Sioux balked. Why should they buy back land that was stolen from them in the first place? And there was another problem. They were broke.

A rusting car sits out in a field on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. 80% of the people here are unemployed.

Third World America

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation is one of the most impoverished places in the United States. 49% of its residents live under the Federal poverty level. 80% of its people are unemployed. The infant mortality rate at Pine Ridge is five times the national average. The teen suicide rate is four times more than the rest of the country.

A drive down the main street of Pine Ride is like a visit to a third world country. The idle and destitute squat in doorways and linger in alleys, drinking and smoking. Alcoholism is estimated to afflict 80% of Lakota families. One in four children are born with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder.

Two Sioux horsemen ride down the street on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Ponies were possessions of great value to the Sioux. When the army took Sitting Bulls’ ponies he negotiated to get them back, to no avail.

The obvious question is, Why don’t the Sioux do something about it? Other Native American tribes have been able to flourish in recent years with the addition of casino gambling. The 320 members of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe of Connecticut, for example, have become fabulously wealthy operating the Foxwoods Resort Casino, the second largest casino in the U.S. But the Sioux, while they have dabbled in the casino business, seem less committed to such enterprises than other Native American peoples.

It likely has much to do with a long standing social divide among the Sioux people, the divide between progressives and traditionalists, between those who favor greater assimilation with the dominant culture and those determined to maintain traditional Sioux ways. The divide goes all the way back to 1890, the year of the massacre at Wounded Knee, one of the most shameful chapters in US history.

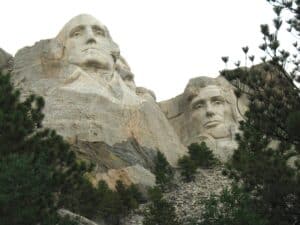

40 policemen gathered to arrest 60-year old Sitting Bull. Then they lost control of the situation and shot him, triggering a tragic series of events.

Bootlickers and Renegades

The massacre had its inception fourteen years earlier at the Battle of Little Bighorn. There in 1876 the 7th cavalry of the US army under General George Armstrong Custer was annihilated by the combined forces of the Cheyenne, Arapahoe and Lakota Sioux. The affect it had on white Americans of the time, especially white settlers in the West, was akin to the shock and outrage of 9/11.

Urged to do something, the US government responded by increasing its efforts to bring Native American tribes to heel by wiping out their native game, pushing them off their traditional hunting grounds, and confining them to reservations. Efforts were made to legitimize these actions with treaties and agreements.

In signing the agreements the Native Americans sought just compensation for what had been taken from them. The government agreed to provide food, blankets and farming implements at regular intervals to help a dispossessed people whose traditional means of survival was being slowly and deliberately wiped out.

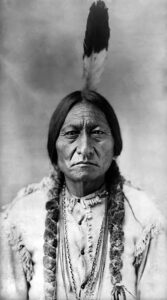

Sioux encampment at Pine Ridge in 1890 at the time of the Wounded Knee massacre. 350 Sioux men, women and children had gathered beside Wounded Knee Creek.

All of this seemed quite reasonable on the face of it, but before long many Native Americans came to rely on the monthly distribution at the tribal agency, an outpost on each reservation where a government agent held sway. In short order the agent, invariably a white man appointed by the federal government, became a minor potentate, and the Native Americans became despised supplicants.

Before long, a good many white settlers, themselves struggling to make it as farmers in the harsh Dakota environment, began to view the situation as a form of welfare. The Native Americans were taking government hand-outs and doing nothing to earn it. They were accused of being lazy leeches. And the criticism wasn’t just from whites.

Site of the Wounded Knee massacre today. This land is of great importance to the Sioux, but they don’t own it.

Traditionalist tribe members lambasted their fellow Indians for being cowardly bootlickers. Traditionalist leaders like Sitting Bull and Big Foot had long stood for resistance and opposed treaties, and they were especially aggrieved when the agreed upon distributions were deliberately scaled back, pushing their people toward starvation.

Bad Medicine from a Bad Pharmacist

In the 1880’s postings at Indian agencies were government patronage jobs, handed out as plums to dutiful political supporters. During the administration of President Benjamin Harrison those agency jobs were considered particularly rich rewards because appointees who ran Indian agencies were furnished with significant wealth and goods to distribute as they saw fit.

A young Sioux man drying a rattlesnake skin outside the makeshift museum on the site of the Wounded Knee massacre.

The agency for the Pine Ridge Reservation was rewarded to Daniel Royer, a failed medical man and pharmacist whose sole qualification for the job was his success at drumming up votes for the Republican administration. Upon his arrival at Pine Ridge he was confronted with a worrisome new development – worrisome, that is, for someone who knew nothing about Native Americans.

The tribes had begun to embrace a new religion, a mystical dance that involved moving around in a circle, stooping to pick up dirt and throwing it in the air, all the while chanting a rhythmic sequence and striving to fall into a trance where mystical visions would be revealed. Proper performance of the so called Ghost Dance unveiled a coming world where the living would be reunited with the dead, illness would be eliminated, the buffalo would roam the plains again, and the whites would vanish.

Today the site of Wounded Knee is maintained as a memorial by the Sioux. A large explanatory sign details what happened.

Long time army officers, veterans of the plains, and others experienced with Native Americans thought nothing of the Ghost Dance, seeing it as an act of desperation by a starving people, but neophytes like Royer were unnerved; they heard its message of vanishing whites as a threat and wanted it stopped. When the Native Americans refused, Royer called in the troops, a ridiculous overreaction. But Royer was not alone in his overreaction to the Ghost Dancers.

The Massacre

Agent James McLaughlin of the Standing Rock agency was also fed up with the Ghost Dancers. McLaughlin had Sitting Bull on his reservation and worried that the old Sioux leader would try to stir up trouble. When the Ghost Dance took hold, Laughlin’s worries deepened, and he arranged to have Sitting Bull arrested, to prevent what he saw as a potential uprising.

Tragically, the attempted arrest was reckless and heavy handed. 40 policemen showed up to arrest an enfeebled 60-year old man, and in the course of taking him into custody shots were fired. Sitting Bull and eight of his followers were killed.

Fearful that government soldiers would seek to slaughter them as well, 200 of Sitting Bulls followers fled south to join Chief Big Foot on the Cheyenne Reservation. Of this group 38 Sioux under Big Foot continued further south to take refuge with the Lakota Sioux encamped beside Wounded Knee creek on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Soldiers bury the Indians in a mass grave at Wounded Knee. When it was over 300 Sioux lay dead. 200 of them were women and children.

Following the debacle surrounding the killing of Sitting Bull, the army was terrified of a Sioux uprising and looked to forestall it by rounding up and arresting all the Ghost Dancers in the region. They were particularly concerned about a group holed up in a forbidding stretch of country north of Pine Ridge at a place called The Stronghold. The Sioux in The Stronghold could not be made to surrender, and when it became known that Big Foot was moving south in the direction of The Stronghold, troops were dispatched to intercept him.

Near Porcupine Bluff in the Badlands a detachment of the 7th Cavalry, the same unit that had been ambushed and massacred at the Battle of Little Big Horn, intercepted Big Foot. They were not men likely to be lenient with Indians.

They marched Big Foot and his band, still armed, to the camp at Wounded Knee, and then attempted to disarm them. The Indians resisted. Shots were fired. Soldiers surrounding the Indians panicked and let loose with an indiscriminate barrage, gunning each other down in the confusion. Furious and frightened, the soldiers then went on a killing spree, shooting every Sioux in site, most of them unarmed.

A visiting couple looks over the fence at the graveyard at Wounded Knee. Today the Sioux are faced with having to buy back this land from the white man who owns it.

Of the 350 Sioux assembled in the camp when the firing started, two-thirds were women and children. This made no difference to the soldiers. They kept on shooting. When a number of Indians tried to take shelter in a narrow ravine, the soldiers rolled a cannon to one end and shot down the length of it, murdering most of them.

When a few Indians escaped on foot across country, the soldiers rode them down and exterminated them. One defenseless woman got three miles away before a soldier rode up and dropped her.

When it was over 300 Sioux and 25 soldiers lay dead. 200 of the dead were women and children. Some of the women were pregnant or nursing at the time.

They were buried alongside the men in a mass grave.

First the Shooting, Then the Gouging

A trio of horses wander the hills surrounding Wounded Knee. The land here is not worth much, unless it’s the site of one of the most shameful acts in US history.

Today the site of Wounded Knee is maintained as a memorial by the Sioux. A church, a large explanatory sign and a makeshift museum are located there. But trouble is brewing once again. For the site is not owned by the Sioux. In the years following the massacre the land was divided into allotments and distributed to individual tribesmen to encourage them to become farmers. Not surprisingly, the government also found “excess” allotments which they sold to whites. Among these allotments was the site of the massacre.

This year James A. Czywczynski of Rapid City put the 40-acre plot up for sale. He wants $3.9 million for it. The Sioux insist the land would be worth no more than $7,000 if it weren’t for its historical value. A grotesque irony exists in the fact that the Sioux are unable to afford the land their forefathers were slaughtered on because their forefathers were slaughtered on it.

Czywczynski is willing to sell the land to anyone, but the Sioux are obviously the most interested party. The only problem is that the tribe is currently $60 million in debt. And then there’s the nagging question of having to pay for land that was stolen from them in the first place. Traditionalists say, “Never!” But progressives say, “Let’s swallow our dignity one more time and acquire the property so we can develop it with a proper visitor’s center and bring some tourist dollars in.” The two sides are not in agreement.

The monument to Crazy Horse in the Black Hills of South Dakota was started in 1948. Today it is still far from finished.

Making a Molehill out of a Mountain

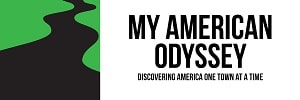

Up the road in Custer County in the Black Hills a similar controversy has been dragging on for years. The Crazy Horse Memorial was conceived as a Native-American answer to Mount Rushmore. Offended that the granite face of a mountain located on sacred Lakota land was being carved into the enormous busts of four US presidents, Henry Standing Bear, a Lakota elder, sought out a sculptor in 1929 to one-up the federal project. The monument he envisioned was to depict the famed Lakota warrior Crazy Horse, and it was to be nearly ten times the size of the faces on Mount Rushmore. Construction started in 1948, and today, six decades later, it is still unfinished.

High iron content in the rock has made it extremely difficult to carve, harsh weather has caused delays, and sluggish financing has slowed the project to a crawl, but the massive sculpture has run into other troubles as well.

Sioux traditionalists disapprove of the project, claiming that the land is sacred and that the carving of a mountain into a statue diminishes its worth. In a sense they are saying, regardless of its size, this is making a molehill out of a mountain, and they don’t like it.

A Signal Victory

Pe’ Sla, 1,942 acres of prime prairie in the heart of the Black Hills is sacred to the Sioux. With the help of internet donations the Sioux were able to buy it back from its white owners.

The disposition of any land returned to the Sioux will be a point of contention for years to come. The argument that developing the land is a surrender to the pressures of the dominant culture, and that doing so dishonors the memory of their ancestors, will be set against the crying need to feed, house and employ the most impoverished people in the United States.

Increasingly, this will be an issue because a trend appears to be emerging in which former tribal lands, long owned by non-Native Americans, are being put up for sale. A case in point is Pe’ Sla, 1,942 acres of prime prairie in the heart of the Black Hills, considered sacred by the Sioux. Long owned by the Reynolds family, who have graciously permitted the Sioux to use the land, it was put on the block in 2012 with an asking price of $900,000.

Dramatic clouds fill the sky above the Black Hills. This gorgeous and haunting country was granted to the Sioux by treaty, and then, ten years later, stripped away.

Running up against commercial banks reluctance to lend, the Sioux desperately sought financing elsewhere and with the kindly assistance of the Reynolds family and a deluge of internet contributions from around the world they secured the financing to buy the property. As of November 2012 the land was returned to the Sioux nation, a signal victory in a long history of struggle and bereavement.

But Pe’ Sla was easy. The land was never meant to be developed. But sites like Wounded Knee and the South Unit of the Badlands National Park are a different story, and years of squabbling about what to do with such places, should they ever be returned, lie ahead.

Thank you for the Land. You’re not Welcome.

The Stronghold was seized by the army and used as a bombing range until 1958. By 1969 the government deemed it “excess” and didn’t know what to do with it. The Sioux wanted it back.

The Stronghold, home to the last Ghost Dancers and sacred land to the Sioux was seized by the army and used as a bombing range until 1958. In the late 1960’s it was offered back to the Sioux with the stipulation that they pay the government the original cost of the land, plus interest. Traditionalists saw this as yet another slap in the face. Again, they wondered why an impoverished people should have to pay for land that was stolen from them in the first place.

Seeing that the Sioux were not going to cooperate, the government made the land part of the National Park Service and annexed it to Badlands National Park, calling it the South Unit. Since 1976 the land has been jointly administered by the National Park Service and the Ogalala Lakota Sioux, but, except for the White River Visitor Center, there has been almost no development of the area. Regardless of what the Park Service and progressives may want, a significant portion of the Sioux, stripped of their land, swindled in treaties and deprived of their way of life, refuse to cave to pressure to develop it for tourism.

Stripped of their land, swindled in treaties and deprived of their way of life, traditionalist Sioux long for justice, even today.

These traditionalists are engaged in a ghost dance with the dreams and aspirations of their ancestors that prevents them from selling out. Which is why casino gambling is not the same panacea to the Sioux as it is to most other Native American tribes, and why there is grinding poverty on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

The Ghost Dance envisioned a perfect world, a vision of an idealized past that would be restored to those who honored the traditional way of life. But the Ghost Dance never delivered on its promise; it only brought the Sioux yet another bitter reminder that their day had passed.

Check it out…

Badlands National Park

Badlands National Park

25216 Ben Reifel Road

Interior, SD 57750

(605) 433-5361

Website

Wounded Knee Massacre Monument

Wounded Knee Massacre Monument

Just north of intersection of BIA-27 and BIA-28

Porcupine, SD 57772

(605) 867-5821

Website

Crazy Horse Memorial

Crazy Horse Memorial

12151 Avenue of the Chiefs

Crazy Horse, SD 57730-8900

(605) 673-4681

Website

Previous stop on the odyssey: Bayard, NE //

Next stop on the odyssey: Bitterroot Mountains, MT

Sources

Bartecchi, David. The Fate of the Badlands South Unit and a Forgotten History, VillageEarth.org, 14 June 2010, 4 August 2013.

Eligon, John. Anger Over Plan to Sell Site of Wounded Knee Massacre, New York Times, 30 March 2013, 4 August 2013.

Rand III, Martin. A Memorial for Crazy Horse 63 Years in the Making… So Far, CNN-US, 6 November 2012, 4 August 2013.

Richardson, Heather Cox. Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre, New York: Basic Books, 2010.

Schilling, Vincent. Tribes Reach $9 Million Goal and Purchase Sacred Site of Pe’ Sla, Indian Country Today Media Network, 30 November 2012, 4 August 2013.

Schilling, Vincent. Wounded Knee Mystery Bidders Working to Secure Land for Tribe, Indian Country Today Media Network, 8 May 2013, 4 August 2013.

Wikipedia contributors. Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, acquired 4 August 2013.

Williams, Timothy. Sioux Racing to Find Millions to Buy Sacred Land in Black Hills, New York Times, 3 October 2012, 4 August 2013.

Image Credits:

Ghost Dancers, Public domain; White River Visitor Center, NPS.gov; Badlands overlook, Malcolm Logan; Hikers at Saddle Pass, Malcolm Logan; Rusting car at Pine Ridge, Egyptspice; Pine Ridge riders, Pamela Y. Cook; Sitting Bull, Public domain; Sioux camp at Pine Ridge, Public domain; Wounded Knee site today, Malcolm Logan; Young Sioux man, Malcolm Logan; Wounded Knee sign, Malcolm Logan; Big Foot dead at Wounded Knee, Public domain; Mass grave at Wounded Knee, Public domain; Graveyard at Wounded Knee today, Public domain; Horses, Malcolm Logan; Crazy Horse Memorial, Navin75; Mt. Rushmore, Malcolm Logan; Pe’ Sla, Malcolm Logan; Black Hills clouds, Malcolm Logan; The Stronghold, Malcolm Logan; Pine Ridge Sunset, Adam Pearlstein