There are innovations that, when we first experience them, are so striking, so clearly a terrific idea, that we cannot conceive of their ever fading away. For anyone born before the year 2000, the indoor shopping mall was one of those things.

Repositories of consumer culture and social engagement in a time before the internet, indoor malls beckoned us with an enticing array of goods in a safe and comfortable setting apart from the weather. They were a place to meet and socialize, to dine and shop. Those of us who experienced them when they were new never thought of them as a cultural phenomenon that would fade with time. They were just a great idea that would be with us forever. How wrong we were.

A Utopian Vision

In one sense, indoor shopping malls are as old as civilization. The ancient Greeks had sheltered marketplaces called agoras as early as the 4th century BC, and the ancient Romans had arcades and porticos lined with storefronts, some of which can still be seen in places like Bologna, Italy today. But somehow the idea of a fully enclosed indoor marketplace got lost in the West during the Middle Ages and wasn’t revived until the late 20th century when Americans began moving from the cities to the suburbs.

The indoor shopping mall as we know it has everything to do with the growth of the suburbs. Like the suburbs themselves, indoor shopping malls are an idealization, a futuristic fantasy of what the world could be, as imagined in the 1950’s. Indeed, the architect of the world’s first fully enclosed shopping mall said as much when he spoke of the mall as a place where shopping and socialization, leisure and play could come together to provide a holistic consumer experience, a utopian vision. His name was Victor Gruen, and the place where he would build his idealistic vision was Edina, Minnesota.

An Invitation to Socialize

Victor Gruen was an Austrian of Jewish heritage who fled Nazi controlled Vienna in 1938 and settled in the US. In 1951 he started his own architectural firm and began promoting his vision of a new type of shopping center. His ideas were based on what he knew of European cities with their large central squares and surrounding arcades and passageways. He saw in those European spaces an invitation to socialize lacking in the American retail landscape.

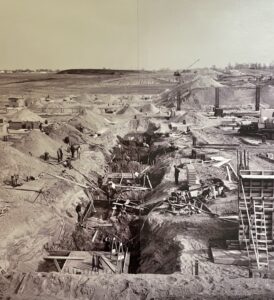

Meeting with the Dayton family, owners of the Dayton department stores in 1952, Gruen got the contract to design a new shopping center in Edina, a suburb of Minneapolis.

The location was significant. The Minneapolis area gets 115 days of precipitation each year, including an average of 53 inches of snowfall. The summers can be hot. To counter this environmental challenge, Gruen proposed a fully enclosed shopping center. The idea was not new. Valley Fair Shopping Center in Appleton, Wisconsin was already on the drawing board when Gruen made his proposal. But Valley Fair had only six stores on a single level. What Gruen was proposing was something much more ambitious.

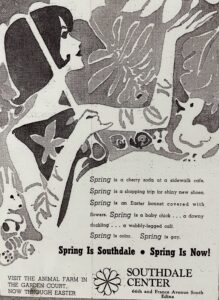

Gruen’s shopping center would cover 800,000 square feet with seventy-two shops on three levels and forty-five acres of parking. Customers could spend all day inside of it, eating, shopping and socializing, even on the coldest days of winter. As the advertisements would come to say, “It’s Always Springtime at Southdale Center.”

Southdale Center

Groundbreaking for Southdale Center took place on October 29th, 1954, and construction was completed in two years. The grand opening attracted 75,000 people who showed up to see Gruen’s daring futuristic vision. What they saw left them gob-smacked.

Gruen had not only built a shopping center, he had built a completely new public space with broad, brightly lit concourses converging on a central atrium featuring plants and flowers, ponds and fountains, art and sculptures, and a two-story decorative aviary filled with brightly colored birds. He had done nothing less than bring the outdoors indoors. It actually was always springtime at Southdale Center, and the place was a sensation. It became the template for shopping malls across the nation, and they began popping up like wildflowers in April.

Within a few years Harundale Mall opened in Baltimore, MD (1958), Big Town Mall opened in Mesquite, TX (1959), and Randhurst Mall opened in Mount Prospect, IL (1962).

The Gruen Effect

But Victor Gruen had loftier ambitions for what his mall should be. In his original vision he imagined hotels and apartment buildings, schools and a medical center, a complete city under a single roof. What he achieved instead was something unexpected, a shopping experience that exerted an almost hypnotic pull on consumers, an oddly euphoric rush triggered by a mixture of familiar sights, sounds and smells.

Among urban planners it became known as the Gruen Effect, a sensation not unlike what one feels in a Las Vegas casino, a feeling of being happily lost in a world of enticements, forgetting one’s original purpose, surrendering to the impulse to spend. Not surprisingly, the Gruen Effect proved too great a temptation for America’s profit minded retailers, and the other parts of Gruen’s vision got pushed into the background.

By the 1980’s his original dream of a unifying social space where people could relax and interact with each other had given way to laser like focus on selling things. Malls became a hyped-up delivery system for consumer goods. Central atriums became an afterthought, a vast, empty space that shoppers passed through on their ways to making purchases. In time it became clear that the Gruen Effect was exerting its greatest influence on America’s most vulnerable consumers, teenagers.

Mall of America

In the days before the internet, the mall was everything to American teenagers, a place to go where they could get away from their parents, a place to meet and socialize, a place to play games, discover new trends, and show off. This powerful aspect of the mall’s appeal was chronicled in the movies of the time: Mall Rats, Weird Science, Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Then exploited.

Opened in 1992, Mall of America was consciously designed to appeal to teens and older children. Located just six miles east of Southdale Center, it remains America’s largest indoor shopping mall. But what makes it so successful is not just its 500 plus retail stores, but the fun houses, thrill rides, movie theaters, and amusement parks that reside within its 2.87 million square feet. In some ways it is the fulfillment of Victor Gruen’s dream: a unifying space where shopping and socializing, leisure and play can come together. In other ways, it falls short.

The Dream Modified

Gruen’s dream was based on a 1950’s idea of suburbia that no longer exists. Suburbia as a peaceful refuge from the city, an escape from crime and blight, a calm, friendly, almost entirely white world where decent, wholesome people stop to chat beside a white picket fence.

Give those people a central square in a climate-controlled mall with a two story aviary and a sidewalk café with pinwheel umbrellas and uniformed waiters, and you might reasonably expect them to dine on tea and croissants, dress in their Sunday best, and take a stroll to do some window shopping. That’s a far cry from the controlled chaos of Mall of America.

Mall of America’s success can be attributed to the frenetic energy of a traveling carnival combined with the hypnotic allure of the Gruen Effect. It is dazzling, enticing and hard to escape. And it is vulnerable to the same social ills that afflict any public space, especially one that’s so openly inviting.

The Last Days of the Indoor Shopping Mall

In December 2013 the First Nation’s protest movement attempted to hold a Native-American round dance in Mall of America. The dance was broken up and the organizers arrested. A year later in 2014, a demonstration by Black Lives Matter was broken up and demonstrators were taken into custody. Two months after that, in February 2015, the al-Shabab militant group called for attacks on Mall of America.

All across the country, indoor shopping malls, once the peaceful refuge of carefree suburbanites have become the targets of unauthorized protests and outright criminality. From break ins in the parking lot to flash mobs and gang warfare, indoor malls have seen it all. For many it was just too much.

Already under siege from recent economic downturns and the rise of online shopping, many malls began losing tenants. Vacancy rates soared. The concurrent demise of the big department stores that once served as anchors for the malls hastened the downfall. Coresight Research, an industry research group, estimates that 25% of America’s 1,000 indoor shopping malls will close in the next three to five years, and the pandemic has only accelerated that decline. What we thought would be with us forever is rapidly dying. Springtime doesn’t last forever.

Epitaph

Temporarily closed or closed for good? 25% of America’s indoor malls are projected to close in the next five years.

Given everything working against it, it’s hard to believe that Southdale Center, Victor Gruen’s original concept, the world’s first fully enclosed shopping mall is still open, if barely. On a recent trip to Edina, I walked the nearly vacant concourses, past shuttered stores, idled escalators and roped off food courts, a sad testament to the final days of grand dream gone to seed.

On its face, the idea is still a good one. It makes more sense to shop indoors than out. But now you can shop indoors from the comfort of your own home without the hassle of parking and walking, and interacting with people you don’t know. And there’s the rub.

When the final epitaph for America’s great indoor shopping malls is written, it won’t be the failure of indoor shopping as a concept that will be blamed, but the failure of we, as a people, to sit down long enough to get to know each other, to relax and enjoy each other, to socialize without the compulsion to buy things. The indoor mall as originally conceived was supposed to bring us together, but like so much in America over the last fifty years it has only served to drive us apart.

Previous Stop on the Odyssey: Duluth, MN

Next Stop on the Odyssey: Van Meter, IA

My American Odyssey Route Map

Sources

Karlen, Neal. “The Mall that Ate Minnesota”, New York Times, 30 August 1992 Website

Newton, Andrew. Shopping Mall, Bloomsbury Academic, 2017

Thomas, Lauren. “25% of US Malls are Expected to Shut with Five Years. Giving Them a New Life Won’t Be Easy,” CNBC, 27 August 2020, Website

Image credits

The Cleveland Arcade, Public Domain

Victor Gruen, American Heritage Center, Fair Use

All other images by Malcolm Logan