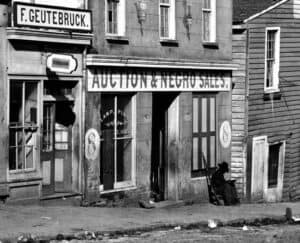

Free labor was not without its costs. By 1860 the price of Negro slaves had risen in Mobile, making it worthwhile to skirt the law and sail to Africa to purchase more.

History cannot be forced on a people. In 1983 the people of Africatown tried to get their neighborhood declared a National Historic Park. It was a non-starter. Not only was their plan opposed by the adjacent International Paper Co. plant, which was reportedly eyeing the land for possible expansion, but none of the original cabins existed any longer. You cannot preserve an idea.

But by far the biggest reason the site was not granted preservation status was that the world outside of Africatown just didn’t seem to care. After all, what can be gleaned from the story of an African community that came together on this spot, flourished for a brief time, and then disappeared? What is there to be learned?

All That Remains of Africatown

Today, all that remains is a solitary mobile home where the shuttered Africatown visitor’s center is housed.

Even now, most Americans don’t know that the last shipload of African slaves arrived in Mobile, Alabama on July 8, 1860, a mere six months before Alabama seceded from the Union, leading to the start of the Civil War. Or that four years later those same Africans, still unable to speak much English, were set free. In the turmoil and upheaval of Reconstruction, they established a community, which they called African Town, on the banks of the Mobile River, and for a brief time they thrived.

Today all that remains is the cemetery where the graves of the original inhabitants can be found, that and a rusty mobile home where the shuttered Africatown visitor’s center was once housed. Even the International Paper Co. plant, which one coveted this ground, is gone, having moved its jobs in 1999.

Today Africatown is a dilapidated community of poor blacks, not unlike thousands of others scattered across the nation. But this community holds a lesson we would do well to remember.

Today Africatown is a dilapidated community of poor blacks, not unlike thousands of others scattered across the nation.With the exception of a few gravestones and a couple of historical markers, a significant piece of American history has been lost.

But Africatown still matters because its story throws into sharp relief the long history of man’s exploitation of man, the dark underbelly of capitalism. Its inhabitants throughout the years have been victimized again and again. To forget about it is to sustain the myth that our economic system benefits us all, ignoring the fact that it is often built on the misery of the exploited, a process that began with slavery but didn’t end there.

The Last Slaves in America

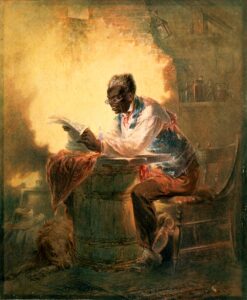

The African tribes from which slaves were taken possessed habits of thrift and communalism that were brought to bear by the founders of Africatown.

Those who believe that the South never shrank from the moral horrors of slavery may be surprised to learn that they rejected a significant part of it as early as 1808, fifty years before the Civil War. In that year an enlightened US legislature with the cooperation of southern lawmakers outlawed the international slave trade, agreeing that the kidnapping of Africans from their homes for the purposes of enslaving them was morally reprehensible.

Ironically, however, that same generosity of spirit didn’t extend to African-Americans already in servitude in the South. Their offspring were to remain in bondage forever. And the reason?

The South’s agrarian capitalism was unsustainable without free labor. Without it, their economy would collapse. Every southerner knew it, but, like so much to do with the Old South, this was a truth that could not be acknowledged. So southerners developed a twisted rationalization for keeping blacks in bondage, citing the inferiority of the black race, which required the benevolent paternalism of whites, without which, it was said, blacks would be unable to take care of themselves.

Meaher’s ship sailed to Africa and purchased slaves that had been ripped from their homes by ruthless warlords.

At bottom, however, it was all about the economy, and nowhere is this more clearly seen than in the motives that led Timothy Meaher to flout the law prohibiting the importation of African slaves to arrange a slaving expedition to Africa in 1860, long after it had been declared illegal.

Over time, the outlawing of the international slave trade had had an adverse effect of the price of slaves. Without a steady inflow of new slaves, the demand for free labor soon outpaced the supply. The number of children being born to existing slaves was not enough to supply the demand, and, as result, by the late 1850’s the price of slaves had skyrocketed.

After learning of their freedom, many former slaves had no idea what to do next. The newly arrived Africans, however, banded together and saved enough to buy their own land.

Meaher, an astute businessman of questionable scruples, saw an opportunity. Slaves could still be bought on the east coast of Africa for pennies on the dollar and resold in the United States at great profit. The risk lay in evading British and American patrol ships tasked with arresting those involved in the trade. To people like Meaher, such government busybodies were tampering with the free market. This was America. A businessman should be permitted to do what he wanted without the burden of government regulations.

Meaher’s ship sailed to Africa in 1860 and purchased slaves that had been ripped from their homes by ruthless warlords using extreme violence. Several times on the voyage back, Meaher’s ship and crew narrowly escaped being arrested. But on July 8, 1860 Meaher’s ship the Clotilda arrived in Mobile, delivering the last African slaves to the United States.

The experience of these hapless captives mirrors that of other slaves brought to the United States. What sets them apart is the brevity of their enslavement and the resourcefulness of their cultural endowments. After just four years in bondage, they were set free, and they made the most of it.

Relying on habits of thrift and communalism still fresh in their minds from their lives in Africa, they managed to pool their resources and acquire land on which they built a town they christened African Town. From that foundation, they began to climb into the middle class. And then the whites noticed.

The convict leasing system was slavery in all but name. In 1899 90% of prisoners in Alabama were black.

Back into Bondage

By the late 1870’s the North’s experiment with Reconstruction in the South had largely ended and southern whites had begun to reassert their authority over their former chattel. White Supremacist movements like the Klu Klux Klan grew rapidly in membership, and black aspirations were cruelly put down. New systems designed to exploit blacks for their free labor emerged, some differing from slavery in name only. One such was convict-leasing.

Sharecropping was another system by which powerful whites extracted free labor from disenfranchised blacks in the decades following the Civil War.

In 1899 the son of one of the original founders of African Town killed another black man who by all accounts had been harassing him. It may have been self-defense. In any case, he was convicted and sent to prison for five years. His case was somewhat unusual in the severity of his crime. Most blacks in southern prisons at the time had been sent there for petty transgressions or for trumped up charges. 90% of the prison population in Alabama in 1899 was black.

Prisoners were leased out to private businesses, farms and mines, where they were forced to work to pay for their crimes. They were kept in chains and whipped into submission. Not incidentally, they made their masters highly profitable.

Under Jim Crow laws, whites could bring charges against blacks on a whim, demanding from them whatever assets they had. In Africatown those assets included land.

At the same time, a system of sharecropping had emerged in which blacks were offered food and housing in exchange for a share of their crop. It was a simple matter for unscrupulous farm owners to ratchet up the cost of room and board until it exceeded the value of the crops, thus ensnaring the sharecroppers in debt and binding them in servitude.

As the owners of their own land, the residents of African Town mostly avoided the trap of sharecropping, but the weight of the outside world certainly took a toll on them. The second and third generations turned their backs on their parents’ African traditions, binding themselves to the larger black community and surrendering the solidarity that had kept them insulated and protected.

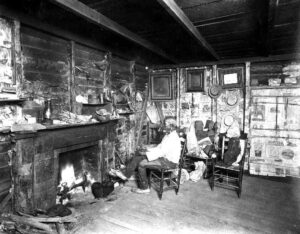

Cudjoe Lewis, seen here in his cabin in the 1930’s, was the last surviving African slave in America. By the time of his death, he had been forced to sell off most of his land.

Along with the rest of the Negro south, they soon became the victims of Jim Crow laws, which sought to disenfranchise them and wrest from them whatever small birthright they had earned. In African Town this took the form of land, the only asset available to settle their debts.

Putting Them in Their Place

In accordance with the Jim Crow laws, blacks could be arrested and fined for a wide variety of petty offenses ranging from vagrancy to disturbing the peace. Allegations were at the whim of any white person who cared to bring them, and convictions at the hands of all white juries were a foregone conclusion. In this manner, black assets were transferred from blacks to whites, from the poor to the rich, from the weak to the strong.

The mighty Cochrane-Africatown Bridge is footed on land that once belonged to the last African slaves in America.

At this point, it’s worth noting, that free labor is never really free. Slaves cost their owners plenty, not just the price of their purchase but the ongoing price of feeding and housing them. It cost something to lease prison labor, and those who hired sharecroppers certainly bore costs associated with the practice. But in each case the compensation for work was shifted away from the person who toiled to another person who unfairly benefited from it. In other words, the labor was stolen, usually by those in power.

In African Town in the early 20th century a pair of railroad accidents left two of the town’s principal black landowners injured and unable to work. Unwisely, they sued the railroad for negligence. One died before the issue was resolved. The other lost his case on appeal and was ordered to pay the court costs. The result was that the railroad, one of the wealthiest and most powerful institutions in America, paid next to nothing for its negligence, while two honest, hardworking black men were physically and financially encumbered. The rewards of their labor were taken from them.

The community of Africatown today. Nothing is left of the original cabins. Physically, there is nothing left here to preserve, nothing but an idea.

By the mid-1920’s much of the original land that had been in their hands had been sold off to settle debts, including the land at the foot of the Cochrane bridge, and the land that would some day become the property of International Paper.

The descendants of the original settlers, weary of the grinding inequities of their lives, looked to escape. Some fled north to Cleveland, Detroit, and Chicago, seeking work in the factories, further diminishing the community, leaving it a pale reflection of its former self.

In 1931, with most of the damage done, African Town enjoyed a brief revival. Cudjo Lewis, the last remaining survivor of the slave ship Clotilda, was celebrated for his adventurous life as well as his exotic Africanness. At the urgings of white audiences he sang songs in his native tongue and recounted his experiences of being kidnapped, transported and enslaved.

International Paper built a plant adjacent to Africatown. It closed in 1999. Years of dedicated service were rewarded with unemployment checks.

But while those rapt audiences thrilled to the bone-in-the-nose images of black savages being subjugated, they were less interested in knowing how a hard working, resourceful person, rich in land, dedicated to family and community, had ended up in poverty.

Four years later, Cudjo Lewis died, severing the last link with African slavery in the United States.

Forgetting About It

It is an irony that 50 years later, in the 1980’s, an attempt to enshrine the historic significance of African Town was reportedly hampered by a wealthy corporation with evident designs on the land. Some measure of justice might have trickled down if the company had actually gone through with its plans. In that case, the high water mark of enthusiasm for reviving African Town, now called Africantown, might have passed for some worthwhile reason. Instead, after a period of unprecedented growth during which company sales quadrupled, reaching more than $20 billion, International Paper closed its Mobile plant, taking away its jobs, leaving the community bereft of resources and spirit.

The graveyard at Africatown. Here lie honest, hardworking black men who in the years following the Civil War had begun a remarkable ascent, through sheer grit, into the middle class, before being beaten back into poverty.

But the company prospered, and that’s all to the good, isn’t it? In America we celebrate success, we admire achievement. International Paper, like the railroads and slave owners before them, did what they could to prosper. The idea that they should owe some moral or ethical obligation to the people who provided them with labor is liberal balderdash. Right?

After a brief flirtation with labor justice in the 1950’s and 60’s we’ve come full circle back to this. The people who employ us owe us nothing. We should be grateful just to have a job. And should they do us a gross injustice by moving our jobs overseas, by reneging on labor contracts, by hiring unpaid interns or cutting salaries and benefits, we should suffer it with dignity – and submission. These are necessary things to help the “job providers” prosper.

Today, CEO pay is a blatant obscenity, untethered from the metrics of success or failure. Wall Street thrives, regardless of the state of the economy. And those who work for a living watch mutely as their incomes plunge. Perversely, some blame the government, not for failing to protect them, but for trying to protect them, as if an economy without oversight leads naturally to labor justice. The lessons of Africatown tell a different story.

But Africatown will not be a National Historic Site. The cabins are all gone. The people are all dead. And you cannot preserve an idea.

Previous stop on the odyssey: Clarksdale, MS //

Next stop on the odyssey: Andersonville, GA

Sources:

Diouf, Sylviane Anna. Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Hurston, Zora Neale. Barracoon. Unpublished typescripts and hand-written draft, 1931. Alan Locke Collection, Manuscript Department, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

Image credits:

Auction and Negro Sales, Public domain; Africatown visitors center, Malcolm Logan; Dilapidated house, Malcolm Logan; African dance, Public domain; Slave ship, Public domain; Slave reading paper that frees him, Public domain; Convict leasing system, Public domain; Sharecroppers, Public domain; Colored drinking fountain, Public domain; Cudjoe Lewis in his cabin, southalabama.edu/archives; Cochrane-Africatown Bridge, Malcolm Logan; Africatown today, Malcolm Logan; International Paper plant, Pollinator; Africatown graveyard, Malcolm Logan

2 comments

“But Africatown will not be a National Historic Site. The cabins are all gone. The people are all dead. You cannot preserve an idea.”

Africatown has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 2012.

National Park Service, 2280, 8th Floor

National Register of Historic Places

1201 “I” (Eye) Street, N.W.

WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/03/12 THROUGH 12/07/12

ALABAMA, MOBILE COUNTY,

Africatown Historic District,

Bounded by Jakes Ln., Paper Mill, & Warren Rds., Chin, & Railroad Sts.,

Mobile, 12000990,

LISTED, 12/04/12

To be clear, Africatown is on the National Historic Register, but that does not make it a National Historic Site.