Jaimé Palmer with the town of Telluride, Colorado spread out below him. For many of its citizens this wild looking character is the unofficial mayor.

My brother Curt and I were sitting in the dining room of the Little America Hotel in Flagstaff, AZ after our ski trip to Telluride when I said, “Look something up on your phone, will you? See if you can find out the steepest pitch a person can ski without losing contact with the earth and falling off.

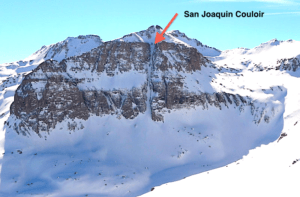

This was a question of some interest to us because of something Jaimé Palmer had told us while we were perched on the edge of an escarpment getting reading to drop into the back bowls at Telluride. Jaimé (pronounced High-May), with his waist length dreadlocks and wild unkempt beard, pointed across the drainage to a towering rock face as flat and steep as a defensive wall and said, “I skied that.”

“I skied that.” Jaimé points to a towering rock wall across the drainage. We squint, trying to see what he’s talking about.

We squinted to see where he was pointing but could make out nothing except an enormous rock wall cut with long vertical fissures. “Where?” we asked.

“There,” he said, pointing with his pole. “Right there in that couloir.” He was pointing to a crack in the rock face, a vertical seam more than 1,000 feet long.

“No way,” we said.

“Yep,” he said.

“Get the hell outta here. How steep is that?”

This is what Jaimé was talking about, the San Joaquin Couloir, a vertical slash with a ridiculous pitch more than 1,000 feet long. Could a man actually ski that?

“Oh, about 60,” he said with his trademark nonchalance. “You have to turn at the bottom to avoid going over a cliff.”

Jaimé’s casual reference to 60 referred to 60-degrees, which prompted the question: How steep a pitch can a man ski before he will simply lose contact with the face of the earth and fall off? Was Jaimé yanking our chains? Was it even possible to ski a vertical slash like that?

These are the kinds of questions that get asked when you are around Jaimé Palmer. He is one of the wildest characters in the west and the unofficial mayor of Telluride.

During his more than thirty-five years at Telluride Jaimé has been menaced by avalanches more than once. Once he was buried six feet under and nearly died.

Avalanche!

My brother Curt first met Jaimé through a friend, Don Palmer, who works on the ski patrol at Wilmot Mountain, the most popular ski hill in the Chicago area. Don has been there for 30 years. Jaimé is Don’s brother. He has been at Telluride for even longer.

Skiing runs in the Palmer brothers’ blood, but their passion has taken them down separate paths. While Don remained in the Midwest, became a geologist and worked at Wilmot on weekends, Jaimé headed out west to Colorado the minute he finished high school in 1977 and took on the life of a ski bum.

The life of a ski bum in the late 70’s was a booze soaked, drug filled bacchanal. But for Jaimé the biggest rush always came from conquering the mountain. He relentlessly pushed the envelope, hunting steeper steeps, deeper powder, bigger leaps. His derring-do often led to danger.

During his more than thirty-five years at Telluride, Jaimé has been by menaced by avalanches on a number of occasions. In most instances he’s skied out of them, which is to say he’s heard the slab giving way, turned to confirm it was cascading toward him, and begun skiing like crazy to stay ahead of it.

Don’t leave home without it. Jaimé demonstrates an avalanche probe of the kind used to find him when he was buried.

If an adrenaline rush is what you’re looking for, having a million tons of snow nipping at your heals will do it every time. As a high it beats the hell out of drugs and alcohol, but like drugs and alcohol it can snuff you out. Jaimé has been sober for decades now. He’s also been buried under six feet of heavy snow.

Once, he got caught in an avalanche so severe it took his friends the better part of an hour to find him using a probe, and by the time they dug him out he had turned blue. Another time, he saved himself at the last possible moment by snagging the upper branches of a tree with his pole as the avalanche swept past underneath him.

When Jaimé tells you these stories you are understandably skeptical. If you don’t know him, his casual, offhanded manner can strike you as the work of a polished con artist. But if you begin asking around, you quickly find there are hundreds of people who can vouch for him. Just about everybody in Telluride knows Jaimé Palmer.

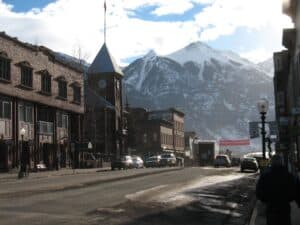

For many years Telluride was known as “the best kept secret in the west”. Isolated and remote, it has long been a magnet for eccentrics and outliers.

Earthy, Open-Minded and Fearless

Jaimé came to Telluride when the old 19th century mining town was just getting on its feet as a ski resort. Outfitted with its first chairlift in 1972, snowmaking didn’t begin on the mountain until 1981. The resort didn’t get its first high speed chair until 1986. For many years Telluride was known as “the best kept secret in the west”. Difficult to access from Denver, tucked away on the western slopes of the Rockies, Telluride is isolated in a box canyon surrounded by deep forested mountains. It has long been a magnet for outliers, eccentrics and others trying to get away.

View from the top. The country around Telluride remains wild and untamed, not unlike the people who live there.

In the late 60’s it became a hippie enclave and still maintains some of its Birkenstock and granola vibe. In the early 80’s it became a drop point for drug smugglers bringing marijuana and cocaine up from Mexico. During that time, it became notorious when it was referred to in the Glenn Frey song “Smuggler’s Blues”:

They move it through Miami, sell it in L.A.,

They hide it up in Telluride,

I mean it’s here to stay

The Telluride Film Festival, which was founded in 1974, raised the town’s profile further when it became associated with the discovery of a number of important filmmakers in the 80’s and 90’s, including Michael Moore (Roger and Me, 1989) and Robert Rodriguez (El Mariachi, 1992).

Skiers heading down Lower Plunge toward the town of Telluride. Today the town is an interesting mix of the down-to-earth and the fabulously wealthy.

Over time the festival earned a reputation for premiering films that were a lot like Telluride itself, earthy, open-minded and fearless, edgy blockbusters like David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, 1986, Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game, 1992, and Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, 2005.

Soon liberal Hollywood had discovered Telluride. Celebrities like Tom Cruise, Jerry Seinfeld and Oprah Winfrey moved in, followed by an influx of lesser known producers, directors and financiers. By the late 90’s, lavish slope side homes and million dollar condos were cropping up all over the place. Before long Telluride was a rich man’s hideaway.

Today Telluride is an interesting mix of the down-to-earth and the fabulously wealthy. It’s a place with a lot of gorgeous upscale residences, very few of which are being lived in. The average value of a home in Telluride is $566,500. The average annual income in Telluride is $38,832. It’s estimated that three-quarters of the town’s homes are vacation homes that sit empty most of the year.

Which turned out to be a good thing for us.

Shuttle Bus Therapist

When I told my brother we were headed to Telluride, he said, “Wait, I might know someone who can get us a place to stay.”

Jaimé’s appearance has been known to frighten small children. But once they get to know him they like him.

I was expecting a dingy ski bum’s digs, linoleum tiles, peeling baseboards, a sliding door that won’t stay on the tracks. What we got was a plush, four-story, multi-million dollar home in a choice location two blocks from the gondola smack in the middle of town. And the magician who pulled off this trick? None other than Jaimé Palmer, the mayor of Telluride.

They call him the mayor because everyone in Telluride seems to know him. To walk down the main street in Telluride with him is like walking along with a politician on a campaign swing, except for the fact that everyone likes him. And Jaimé stops to talk with just about everybody. The conversations run to the usual things skiers talk about: snow conditions, the weather forecast, who skied what run recently under what conditions and what happened to them. It’s genial and friendly, and it ends with a laugh and a light touch on the arm. It’s the essence of community.

Hiking up to the drop in point on Black Iron Bowl. Getting ready for some killer back country skiing.

Jaimé developed this rapport in part because he drives a shuttle bus when he’s not skiing. Others might see this as something of a drudge, but Jaimé sees it as an opportunity to meet people and get to know them, and people warm to Jaimé. Once they get past his outlandish looks (which frankly frighten some children) they open right up to him, tell him things, unburden themselves. Jaimé advises them. This wild looking character, like something out of a 1970’s caveman movie plays the role of unofficial therapist. His openheartedness and generosity are roundly applauded.

Jaimé scored us our posh slopeside lodgings for the $40 price of the cleaning fee and then volunteered to be our guide for two days. If you are going skiing at Telluride, there is no better guide because, arguably, no one knows the mountain better than Jaimé, and his enthusiasm is contagious, but you had better be an expert skier because Jaimé likes to get after it.

Standing at the edge, getting ready to drop in. Telluride has some of the best back country skiing in the country.

Black Diamonds on a Bluebird Day

We were five. Along with my brother and myself, we were joined by Jaimé’s brother, Don, and an old friend and colleague of ours, Andrew Knowles, who had come down from Boulder to join us. In short order Jaimé had sniffed out our abilities and had us ripping down a range of challenging terrain from steep headwalls to gnarly mogul fields to heavily wooded tree runs. It was a joy.

To make matters even better, we had arrived on a bluebird day. The sky was clear and sunny which made the snow a little soft but by no means mushy and every run on the mountain was open. We skied from one end to the other and impressed Jaimé by going bell to bell, heading up on the first lift in the morning and skiing non-stop until the last lift closed late in the afternoon.

Along the way, there were remarkably few mishaps, just a couple of minor spin outs in the bumps and one notable crash where Don performed a yard sale while rocketing out into the flats. Jaimé described this in his colorful language by saying, “Don exploded.”

Late on the second day, I got separated from the others and ended up going down a run that was closed. It was called Cat’s Paw and would’ve been a monster in any case, but ungroomed with exposed rocks and underbrush it was a beast and, by the time I finally broke free, the evidence of my difficulties was plain on my coat and pants which were caked with snow. Jaimé summed it up succinctly when he observed, “Malcolm got his ass handed to him.”

Describing a crash that occurred in the couloirs of the back bowls Jaimé described the victim as “starfishing” down the mountain. Another high speed crash involved a skier “tomahawking” for more than two hundred yards. That particular victim had “the top of his skull peeled back”, as Jaimé described it. “But he was all right, ” he said. “He only took about sixty stitches.”

This casual attitude toward trauma and disaster is the hallmark of extreme skiers, and Jaimé owns it in spades, but we didn’t know how much until later when we were sitting in that restaurant in Flagstaff and I asked Curt to look something up. “What’s the steepest pitch a person can ski without losing contact with the earth?”

Screaming Down the Slopes

Curt punched it up on his iPhone and as the article came up his eyes widened. “You won’t believe this,” he said.

The answer is 67 degrees, but that’s not what surprised him. What surprised him is that the answer came up next to an article about extreme skiing that began with this sentence, “Extreme skiing legend Seth Morrison may have been surprised to see a fifty-something hippie charge by him, dreadlocks akimbo, as his entourage shot film in Telluride’s iconic San Joaquin Couloir.”

Will the mayor yield the chair? Yes, at the top of the lift. Jaimé relaxes and rides solo to the top of his mountain.

A little further on the article continues… “The skier who raced by him is the true maven of the Telluride extreme. Jaimé Palmer is the elder statesman of a motley pack who gather at the bottom of Chair Eight most mornings during the ski season in search of freshies and adrenaline fixes. And he could be the most experienced back country skier alive.”

We had just spent two days screaming down the slopes with one of the most experienced back country skiers alive and didn’t even know it.

Jaimé is not one to brag. So you can add humility to the long list of things that make him special. He is friendly, generous, funny and completely wild. Those attributes may not win him many votes in Peoria or Little Rock, but in the shadows of the San Joaquin Couloir they make him the unofficial mayor of Telluride.

Previous stop on the odyssey: Marfa, TX //

Next stop on the odyssey: Monument Valley, UT

Sources:

Quoted article is from Extreme Telluride, Telluride’s High Mountain Bazaar, 15 January 2014, acquired 26 March 2014

Image credits:

All images by Malcolm Logan, except San Joaquin Couloir, David Hewitt; Avalanche, Ilan Adler, www.Putchka.com; Skiing out of an avalanche, Lukas Polacek; Skier, Florian Linder