The ghosts of children are said to haunt the abandoned hallways of the Concho Indian Boarding School in Concho, Oklahoma. Paranormalists take their EVP recording devices to the school and pick up the sounds of disembodied voices. The air grows chilly. Doors slam. Objects come flying out of nowhere.

The school is actually a complex of buildings on the fringes of the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation in central Oklahoma, just north of El Reno. As Indian boarding schools go, it is neither as old nor decrepit as other such institutions throughout the U.S. In fact, it wasn’t even built until 1969 and functioned for only 12 years before closing. The school is surprisingly modern and up to date. Nevertheless, it is haunted.

Perhaps students at the Concho Indian School had a harder time than their counterparts at other Indian schools. Perhaps, as popular perception would have it, they were ripped from their families, forced into a harsh regimen that stripped them of their dignity and native traditions, were made to serve white overseers who exploited and degraded them, and ultimately killed themselves in an effort to escape, so that now their tortured spirits haunt the hallways and classrooms, moaning for redress.

Sounds dramatic and compelling. But it overlooks one important point. Most Native-Americans were in favor of the boarding schools. When they were finally closed, many Native-Americans were sorry to see them go.

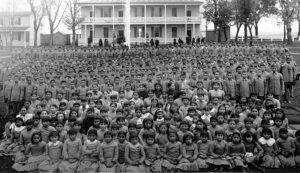

The assembled student body at the Carlisle Institute, an Indian boarding school run by visionary founder Richard Henry Pratt. (Click any picture to enlarge).

To Obliterate Their “Indianess”

How could the victims of such a plainly exploitative system be in favor of it? From our vantage point in the 21st century, it’s easy to lose sight of the facts of Indian life in the late 1870’s when the schools were first established.

After two centuries of conflict, the last of the great Indian wars had ended in the defeat and subjugation of the Sioux. Further resistance was futile. The buffalo herds had been wiped out. A life of hunting and gathering was no longer possible. Most Indians had been forced onto reservations and given allotments of land to farm, but lacking tools and skills, could not effectively farm them.

Pratt and his students on the front steps of the main building at Carlisle. Pratt was a reformer who meant well, and his students liked him.

In the growing white communities nearby, Indians were seen as a potential threat, feared and reviled. A popular sentiment at the time was that “the only good Indian was a dead Indian”. Genocide was in the air and seriously considered.

It was into this atmosphere that a visionary reformer named Richard Henry Pratt first introduced the idea of an Indian boarding school, one that would remove children from the reservation at an early age and take them away to an institution overseen by whites to be immersed in white culture where they could learn white values, to obliterate their Indianness and teach them how to get along in the world as it existed.

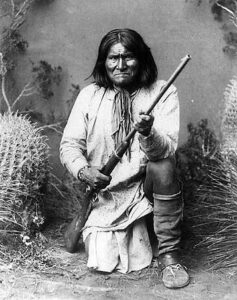

Compared to genocide, Pratt’s boarding school idea appealed to many Native-Americans who saw it as the only reasonable way forward. No less a light then Geronimo, speaking to an audience of students at an Indian boarding school in the 1880s, said, “You are here to study, to learn the ways of the white man. Do it well.”

Indian school students conducting physics experiments. Most students came away with positive views of their experience.

By 1902 there were 25 federally funded boarding schools in 15 states and territories, with a total enrollment of over 6,000 students, and more were being planned.

The Children’s Plight

Canadians and Australians had similar programs of forced assimilation for their native peoples, both of which were more stringent and abusive than the American system. But that’s not to say that the American system was without its flaws.

While many Indian parents were willing to send their children away to boarding schools, some resisted. Under threats of imprisonment or loss of rations, most eventually caved. There were heart rending departures, wailing children, distraught parents. Once the children actually arrived at the boarding schools, often hundreds of miles away, their cultural identities were immediately under assault.

Even the famous Geronimo urged Indian school students to study hard and become more like the white man.

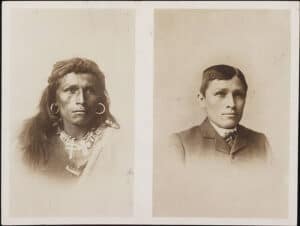

They were shorn of their long hair, deprived of their native dress, given uniforms and assigned new, more pronounceable (ie., white) names. They were forbidden to speak their native languages, even to each other. Those who resisted were threatened with punishments ranging from beatings to confinement.

Yet as cruel as it may seem to us today, it’s important to remember that those in charge of these institutions were, for the most part, reformers who genuinely had the student’ best interests at heart. It is also worth noting that although corporal punishment was always available to administrators, at most schools it was used sparingly, as a last resort. Indeed, most teachers and administrators exhibited sensitivity to the children’s plight and worked hard to ease their transition into the new culture.

The proof of their good intentions can be seen by the fact that most Indian children who remained with the institution for the full term came away with positive views of their experience. After all, they had acquired a new language, received important coping skills, and learned a range of useful vocations. The real problem started when they returned home to the reservation.

In spite of the reformer’s best efforts, tribal life was frequently nearby. Here some Indian parents have assembled their teepees near a boarding school.

Intolerable Backsliding

Although boarding school had prepared them to be farmers and factory workers, on the reservation the graduates found neither factories nor farms. The factories were hundreds of miles away in the major cities, and most Indian farmland was either not arable or had been leased out to white farmers. The life of a reservation Indian in the late 1880’s was largely one of dependency on the agency, an arm of the federal government that doled out rations and goods.

Students who returned to the reservation after boarding school often found few other options but to work for the agency or go on the dole. Before long many slid back into their tribal ways, much to the chagrin of the boarding school officials who had worked so hard to educate them out of them.

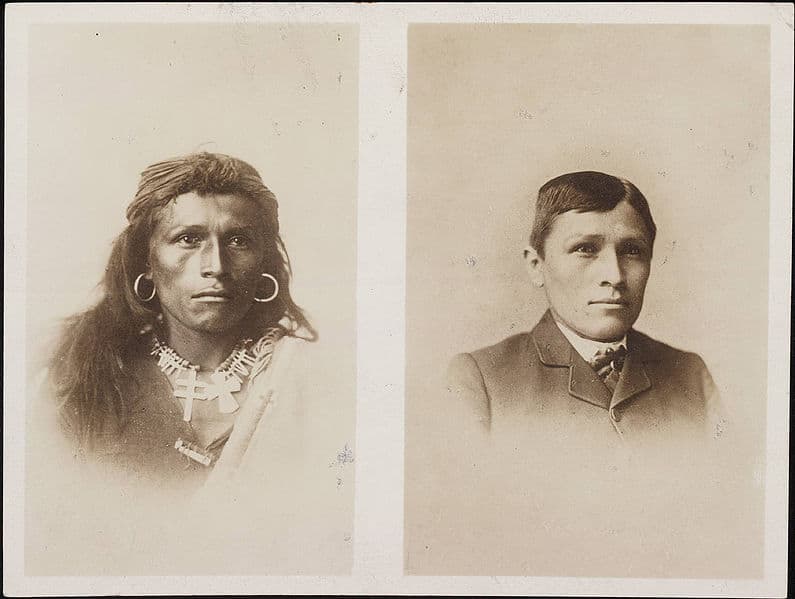

Opportunities for graduates were thin. On returning to the reservation many slid back into their tribal ways.

Consequently, by 1909 the boarding school system was coming under increasing criticism. Some declared it a failure. In a development reminiscent of the present day, powerful conservatives in Washington moved to reform and defund it.

But the boarding school system didn’t go away. Large institutional boarding schools located far from the reservation gave way to smaller schools located nearby. Because of poor roads and the difficulty in reaching the schools from the far reaches of reservations, many of these schools remained boarding schools. In fact enrollment in Indian boarding schools didn’t peak until the mid-1970’s when another round of budget cuts closed the majority of them.

Haunted by Abuse

The boarding school at Concho began its life in the nearby town of Darlington in 1887. In 1932 a new school was built at the present location. In 1969 that school was replaced by the current institution which was defunded in 1981 and shut down. Today it sits abandoned, a playhouse for ghosts and the people who investigate them.

Rumor has it that the school burned at some point and that a number of teachers and students were killed, but there is little evidence of that. The school looks exactly like what you would expect, a once thriving institution abruptly abandoned that became the prey of vandals who broke windows, tore out walls and covered everything with graffiti.

Paranormal investigators are ambiguous about what supposedly happened here, although they do claim to have communicated with the spirits regarding the matter. The implication is that some horrible abuse unfolded here. Indeed, an Amnesty International investigation of Indian boarding schools in the 1970’s and 80’s revealed widespread sexual abuse. In one case, a teacher at a Bureau of Indian Affairs run school on the Hopi reservation raped or molested as many as 142 boys before being arrested. In recent years, members of the Sioux Nation have filed a class action suit for $25 billion against the United States for trauma caused by abuses occurring in government run boarding schools.

Outrage

How common these abuses were is a matter of dispute. But to those who bristle at the very idea of forced assimilation they provide ample evidence of the evils of such a system. Whatever heinous abuse was committed at the boarding schools, plenty of good came of them too. And yet the fact remains, many Native-Americans favored the boarding schools. For every tale of heinous abuse perpetrated at a boarding school, there are many more tales of sincere teachers doing good work to help educate and uplift Native-American children.

Like the outcry directed at the Catholic Church for its abuses, those with an ax to grind will find plenty here with which to cudgel the institution. But lest we be blinded by our outrage, let’s remember that under this same system good people with good intentions labored to help those in need find a way forward, and their efforts have been recognized and appreciated by the communities that they served.

The Concho Indian Boarding School may be abandoned and haunted, but the US government’s 125 year effort to provide Native-American children an education is not something we should shrink from in horror.

View More Images of Concho Indian Boarding School (50 + images)

Images of Concho Indian School by Mr. Fiend at Urban Exploration

Images of Concho Indian School by Billy Dixon at Abandoned Oklahoma

Previous stop on the odyssey: Jasper, AR //

Next stop on the odyssey: Bandera, TX

Sources:

Adams, David Wallace, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928, University Press of Kansas, 1995.

Smith, Andrea, Soul Wound: The Legacy of Native American Schools, Amnesty International, 26 March 2007, 5 January 2012.

Selfridge, Christy, Case File: Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Boarding School, O.K.P.R.I.: Paranormal: The Normal Not Yet Understood, 26 August 2006, 5 January 2012.

Dixon, Billy, Concho Indian School, Abandoned Oklahoma, 15 Nov 2011, 5 January 2012.

Image credits:

Before and after Navajo, Public Domain; Concho Indian School, Billy Dixon – Abandoned Oklahoma; Assembled student body at Carlisle, Public Domain; Pratt and students, Public Domain; Indian school students conduct experiments, Public Domain; Geronimo, Public Domain; Teepees before Indian school, Public Domain; Shoshone tribal dance 1892, Public Domain; Concho Boarding School 1887, Western Oklahoma Historical Center; Blighted hallway, Urban Exploration Resource; Ghostly hand, Richard Nelson

5 comments

Well, if children were taught to recognize the divinity within themselves and others at an early age in a spiritual way without religious dogma attached, people would recognize their built-in alarm system when an action felt wrong. Cultures have been able to convince individuals that harmful actions are justified for the benefit of some at the expense of others because individuals are not taught the skills to learn self knowledge. We revere saint-like historical figures because they have stood up to culturally accepted abuses. In these current times there are examples of well meaning efforts that will prove to have been abusive. Violence is popular entertainment and we don’t recognize the need the protect children from constant exposure because it is “popular”. Toxic food is produced and consumed because we have been convinced to accept convenience over nutrition. We continue to use our resources as if we are separate from nature, because we have been taught so culturally. So, in my view, questions such as forced assimilation cannot be addressed without recognizing that we all live within myths of our own creation and

working toward self knowledge through meditative contemplation can give us the answers we seek. Thanks for another thought provoking article!

Thanks, Joan, for your thoughtful response to this article. I agree. If some people weren’t always about the business of perverting a well meaning enterprise to their own agenda we would not get those few bad apples in the barrel that spoil the whole bunch. But the media never reports on the 100 good apples in the barrel. They only report on the one bade one. So the whole barrel gets dumped. Such a shame. Such a waste.

[…] stop on the odyssey: Concho, OK // Next stop on the odyssey: Ft. Bowie, […]

Im an Indian an my grandmother told me bad story’s of this place. our elders believed it to be a place of the white man that down graded us. an stripped us of any of our beliefs. many childern from my tribe were taken an some where never heard from again. i hate the thought of this place.

I am also part indian and I grew up in Calumet, Oklahoma which is very close to Concho, Oklahoma and yes i do agree with you Jenny they did do these things to our elders our family our loved ones. This one I do remember because I was in it not as a student who lived there but as a student from another school playing sports there and even when we played there you could see past students from long ago in the halls and in the locker rooms you could feel the past around you you knew these children we being hurt and mistreated in the past even now as i speak about it i get the cold chills and the goosebumps again. Even after it was shut down I was known to drive that way to get home at night and you could see the lights from the school and the power had been shut down there for years…..but if we learn from our past we can make a difference in our future love