It would make your eyes burn. It would irritate your throat. Those who tried to use it as a lamp oil ended up with a thin layer of greasy soot on their skin. Those who had used it as a patent medicine reported poor results. It was more than useless. It was a nuisance. In western Pennsylvania it lay on the surface of creeks and rivers in iridescent slicks. It bubbled up in farms fields, flooding crop rows, fouling grazing land.

But then in 1850 Samuel Kier of Pittsburgh found a way to make it burn without the smoky residue and the commercial viability of it as a cheap substitute for whale oil lured two New York entrepreneurs to western Pennsylvania to look into it.

A Burning Interest in the History of Oil – or Not

160 years later I was headed there myself. I had to take State Route 322 off of I-80 for 60 miles; no interstate goes there. The region is hilly and rural. In the first blush of spring, it was verdant and in bloom. The curving bow of the Allegheny River glittered in the sun. It was hard to square this bucolic image with the grime and industry associated with the place.

My mission was to discover the region where oil first made its appearance on the world stage. Most people wrongly assume that’s Texas. But it was here in Venango County in western Pennsylvania, that George Bissell and Jonathan Eveleth started digging with shovels, trying to get at the stuff. They soon realized the folly of that approach.

I was concerned about what this was costing me. Recently, the price of gas had spiked. To explore the oil sites of Venango County and get back to the interstate was going to cost me about $50. I was hoping it was going to be worth it.

And why wouldn’t it be? Oil was big news these days. The price of oil was skyrocketing, sapping the American consumer, threatening to throw us into another recession, making everyone (except those few who were getting obscenely rich from it) very, very nervous.

Surely, there would be a burning interest in oil, the history of it, its birthplace. People would want to know, in the same way that they would be curious about the early life of a tyrant. How did he get this way? What made him so ruthless? I expected to see lines at the museums, tour buses at the historical sites.

Bissell and Eveleth hit on an idea. Salt wells had successfully used drilling not digging to get at salt. Maybe oil could be extracted in the same way. So they hired a man named Edwin Drake to give it a try. Fortunately for them, Drake was stubborn.

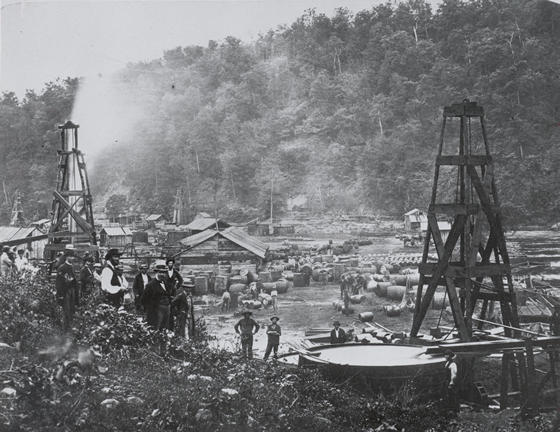

Again and again, Drake’s attempts to drill for oil failed. He built a wooden oil derrick at great expense, among the first of its kind. Still nothing. He begged Bissell and Eveleth for more funding but they rebuffed him. He ran out of money, went into debt. The whole thing was beginning to look like a mistake. And then on August 27, 1859 the world shifted on its axis. Oil blew from the bottom of the well. The oil industry was born.

Mad for Drilling

My first stop was the town of Franklin. The map showed the Venango County Museum located there. I rolled into what proved to be a classic American small town with a village green and a Victorian courthouse. Red brick buildings lined Main Street with striped awnings and doors that jingled as you went in.

I stopped at a historical marker in front of a cream-colored brick building. This was the site of the Galena-Signal Oil Company. Here in 1865 they developed a process for making lubricant oil. Eventually it became Valvoline. Today the building stood empty and had a FOR LEASE sign in front of it. There were no tourists around.

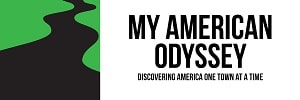

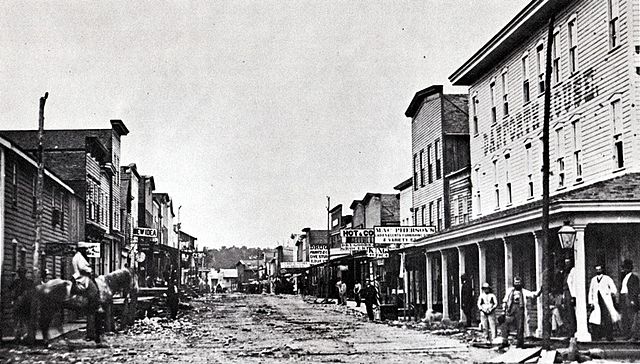

Historical markers were scattered throughout the town, including one that explained how, after striking oil with Drake’s well, Bissell and Eveleth founded the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company in 1854 and started buying up land and selling leases. The oil boom that followed drew more prospectors to western Pennsylvania than had gone to California for the gold rush. The area went mad for drilling. Before long, the hills and dales of western Pennsylvania were bristling with oil derricks. Boom towns sprang up, complete with all the usual vices. Prostitution flourished. Brawls broke out. Gunfights, murders and flim-flammery were the order of the day. Fortunes were made and lost overnight.

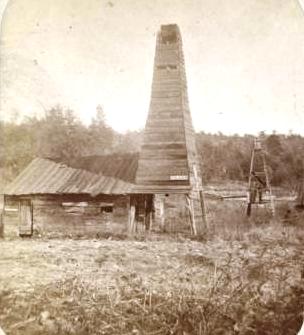

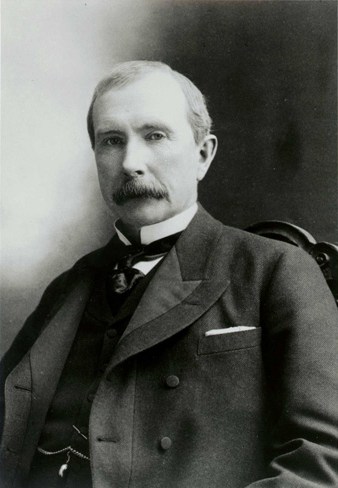

In 1861 John Wilkes-Booth came here, lost all his money, went back home in bitterness and shot the President. That same year a humorless young Baptist visited and was disgusted by what he saw. He quickly concluded that the way to make money was not to vie with ruffians for the commodity itself but to control the means of producing it. Oil could not be made into kerosene without being refined. So instead of buying a lease to drill, John D. Rockefeller went home to Cleveland and quietly bought a refinery.

Oil City and it’s Slick Claim to Fame

I searched around town for the Venango County Museum to no avail. No one seemed to know anything about it. Finally I stumbled on the Venango County Historical Society. A knock on the door produced a little old lady who let me in and evinced complete ignorance on the subject of the region’s oil history. Two other women were sitting down to lunch and seemed mildly annoyed at my interruption. They also claimed a lack of knowledge about oil. They suggested I buy a book. When I asked for the whereabouts of the museum, they said they didn’t know what I was talking about.

I decided to drive up the road eight miles to the town of Oil City. In the early 1860’s Oil City exploded on the map. Not only was it home to a forest of derricks, it was the place where Oil Creek flowed into the Allegheny River and so became the warehousing point for barrels shipped downstream from points further north.

The most efficient way to ship oil in those days was by water and Oil Creek was often crowded with barges loaded high with barrels. It was not uncommon for the barrels to get away, go careening downstream and slam into the bridge pylons at Oil City, resulting in the nation’s first oil spills.

Throughout the 1860’s and 70’s Oil City was a greasy, sooty place, reeking and stained with oil. Today it is an idyllic community stacked neatly on a hillside surrounded by a bend in the river. A quick poke around its vicinity produced plenty of historical markers but nothing in the way of a museum. I decided to keep driving.

From Oil City I ventured up the road to Rouseville. This blip on the map was once a burgeoning oil town. Here was the location of one of the first refineries. It was also, according to a historical marker, the site of the oldest continuously functioning oil well. The marker indicated that the well could be seen just over the bridge. So I crossed the bridge. I found no well.

Pithole City, Boom and Bust

One of the things I particularly wanted to see in the Oil region was Pithole City. In 1863 it didn’t exist. In 1864 they found oil there, triggering a stampede of speculators. By 1865 it was home to several large hotels, a dance hall, a theater, drug stores, barber shops, hardware stores, every modern convenience. It was a bustling community, boasting the third busiest post office in Pennsylvania. But then the oil ran out, and so did the people. By 1866 it was in decline. In 1868 it caught fire, and the whole town burned. By 1870 it was gone.

I followed the route indicated on the map but when I got there I found I had to go another six miles up a narrow, deserted road. I looked at my gas gauge. That was a long way. I was down to less than a quarter of a tank. I drove and drove. At last I arrived.

Pithole City had a modern visitor center. At last, someone to answer my questions. But it was closed. It looked like nobody had been there for a long time.

I wandered the site, a large open meadow hemmed round by a second growth forest. Except for the birds singing in the trees, I was the only one there. What had once been the streets of the town were mere paths through the grass. The former foundations of buildings were indentations in the earth. Explanatory placards had been placed here and there. Some had been vandalized. Others had been knocked over. Nobody had bothered to pick them up. It appeared Pithole City had been abandoned twice.

In 1865 something extraordinary happened in Pithole City. A man named Samuel Van Syckle had one of those crazy ideas that in hindsight seem so obvious but must have seemed outlandish at the time. Pithole City was a long way from the water so the oil had to be carted out in barrels stacked on mule carts. There was a lot of oil and not nearly enough barrels and carts, so the teamsters and coopers started jacking up their prices and the speculators were obliged to pay it – until Van Syckle had his stroke of genius, an oil pipeline, the first in the world.

The Drake Well and it’s Unlikely Beneficiary

From Pithole City I started down the road to the Drake Well Museum and Park. I hadn’t planned to go there, it was another 15 miles, but my attempts to learn about the Oil region from the locals had been a bust, and I was looking for someone, anyone, who cared enough about what had happened there to discuss it with me.

I started on my way but was struck with misgivings when I looked at the gas gauge. The roads were all rural. The likelihood that I would see a gas station was slim. I vaguely remembered seeing a station at Rouseville. So I decided to backtrack. Problem was, a return to Rouseville would require more miles than to carry on to Drake Well. I decided to chance it. It was a mistake.

I haven’t run out of gas in twenty years. It’s sort of embarrassing to do so; modern automobiles certainly give you enough warning. But I had been nursing my fuel, trying to avoid the inevitable. Thus it was I wore a sheepish grin when a pick up truck pulled over to ask if I needed help. I did.

On the way to Rouseville I asked my rescuer, a round faced man in a Pittsburgh Steelers cap if he knew anything about the history of the region. He said he did not, but he understood that there was an interesting museum at Drake Well in Oil Creek State Park. “They’ve got some sort of old oil derrick there,” he said.

The derrick he was referring to was the original well dug by Edwin Drake in 1858. It produced 25 barrels a day at its height. Ten years later the surrounding region was producing 15.9 thousand barrels a day and kerosene was the fuel of choice for a nation.

At the same time, hundred miles to the west in Cleveland, John D. Rockefeller was employing a battery of underhanded methods to buy up his competitors and build a monopoly in refining. By 1879 Standard Oil was refining 90% of the oil in the US. With the invention of the internal combustion engine 20 years later, Rockefeller became the richest man in the world.

Edwin Drake met a different fate. Having failed to secure a patent for his drill, he was widely copied. In 1863 he lost all his money in oil speculation and died impoverished in 1880.

The Pain They’re Causing You

After filling up my car to the tune of $75, I began making my way back to the interstate. Passing through Oil City, I chanced to notice a sign on the back of a building across the river: Venango County Museum. I couldn’t believe it. Having come this far, I couldn’t pass it up.

Inside, a teenage girl seemed startled when I walked in. She hadn’t seen many visitors that day. I told her it was no wonder, nobody in the region seemed to know the museum existed and the map wrongly identified it as located in Franklin. She shrugged.

In 1901 an oil well at Spindletop Hill in Texas began producing 100,000 barrels a day, dwarfing the production of western Pennsylvania. The great Texas oil boom was underway. Western Pennsylvania rapidly declined as a major oil producing region. Eventually even Pennzoil and Quaker State moved their headquarters out of state.

I explored the museum, a three room affair, tidy and well organized, and then I said my goodbye to the girl at the desk and headed back to the interstate.

Something truly extraordinary had happened in western Pennsylvania in the late 19th century. I might have run into a few obstacles trying to learn about it, but maybe my timing was just bad. If you’re interested in the history of oil, a trip to the Pennsylvania Oil Regions is still worth the effort. Here are the address and websites of some key tourist destinations in the area.

Check it Out…

Drake Well Museum, Birthplace of the Oil Industry

202 Museum Lane

Titusville, PA 16354

814-827-2797

website

Pithole City Visitor Center

Map coordinates:

41°31′26″N 79°34′53″W

Website

Venango County Museum of Art, Science and Industry

270 Seneca St.

Oil City, PA 16301

814-676-2007

Website

Previous stop on the odyssey: Lexington, KY //

Next stop on the odyssey: Detroit, MI

Image Credits:

Oil City today, Krystal Layton; Pennsylvania oil field, Public Domain; The Allegheny River, Malcolm Logan; Drake well, Public Domain; Venango County Courthouse, Malcolm Logan; A humorless young baptist, Public Domain; Oldest oil well, Malcolm Logan; Pithole City in 1865, Public Domain; Pithole City today, Malcolm Logan; Edwin Drake, Public Domain; John D. Rockefeller, Public Domain; Venango County Museum, Malcolm Logan

7 comments

Thanks for this wonderful piece. My great great grandfather, Oliver S. Williams of Enfield, New York, took his family to Corning, New York and became a petroleum agent in Oil City, Pennsylvania in 1865. I always knew Oliver was a successful farmer and produce agent in New York state, but family lore was that he had an adventurer’s spirit…a story that his daughter, Libbie (my great grandmother) passed down to my mother…and my mother to me. After years of searching to validate Libbie’s story, I found them in the 1865 New York state census with Oliver’s occupation as “petroleum agent” in Oil City. By 1870 Oliver and his family were back in Enfield and back to the business of produce merchant. I started to look around for some kind of history for Oil City…and found your post. I, too, have taken to back roads and small communities in search of history…with a curious spirit and a dwindling tank of gas.

Thanks, Deborah! Very cool about your family history.

I’m sorry for your bad luck on the day of your visit to the birthplace of the Oil Industry.

You really should have had visited the Oil Creek State Park and the wonderful museum located near Titusville. Not only does the museum there do an excellent job with the history of the Oil Region, but located on the park grounds is the reproduction of the 1st oil well driven by Colonel Drake, as well as many other interesting displays of the early oilfield machinery used to extract and transport the crude oil.

The Oil Creek State park is also know today for the many miles of scenic bike trails along Oil Creek, excellent trout fishing, and the OC&T railroad which is now strictly for tourists wishing to spend a few hours traveling through the valley which changed the world.

I am trying to work on my family Ashbaugh history but not getting where. All I know is my mother lived in St. Petersburg,Pennsylvia and her father was Harlan Ashbaugh. My mother can’t tell me anything and her brother is deceased. So I am hoping someone in Oil Well City or St.Peterburg could help me.

Carolyn,

I grew up in the oil area and have some Ashbaugh relatives

From St. Petersburg. If you contact me through email, I

will try to put you in touch with them. I know they have a

local history book about the St. Petersburg area and the

Ashbaugh family is mentioned in it. That may help you

find out more about your family. Good luck!

Jolene

I know it is years too late but sorry about your luck with the trip. There are few left that care or know in detail about the history of the region but they are around. Drake Well in Titusville is your best source but the true meat is locked away in its library. Same holds true for the Venango Museum, much of their collection is stored away, fogoten, with staff that just don’t bother. Private groups are around that cover every subject from Venango’s pivotal role in the French & Indian War and colonial frontiers expansion to clubs that maintain the railway. The steam & gas engine as well as the blacksmiths club have members that are knowable in oil history from a technical perspective. The regions influence didn’t start with oil ether. It was a hub for the Indian fur trade, then timber, iron, and just a little east you will find coal. It’s location, recources and industry played a roll in every American/Colonial war since the French&Indian War in the 1750s.

The big problem is finding people that care anymore and those of us that do ether have moved away (me) or dont have the ability/resources.

The tourism slogan is “The Valley that Changed the World” but really it is “the valley the world forgot”

I’m amazed that you made the trip to the area–even visited Pithole and never went to Drake Well. Most would start with Drake Well, a museum that is quite interesting and worth viewing. Sadly, though, it is true that many in the area know nothing of oil history. I can’t believe that you didn’t see the world’s oldest producing oil well. You say it is across the bridge. Where did you get that idea? The sign says it is across the railroad tracks, not the bridge. It was not far from the sign. (Now, from your photo, it looks like it may be that the railroad tracks have been abandoned and removed.) The history here is truly great. In so many ways, though, it is history–so much of it is long gone. If in the area again, do give Drake Well a try.