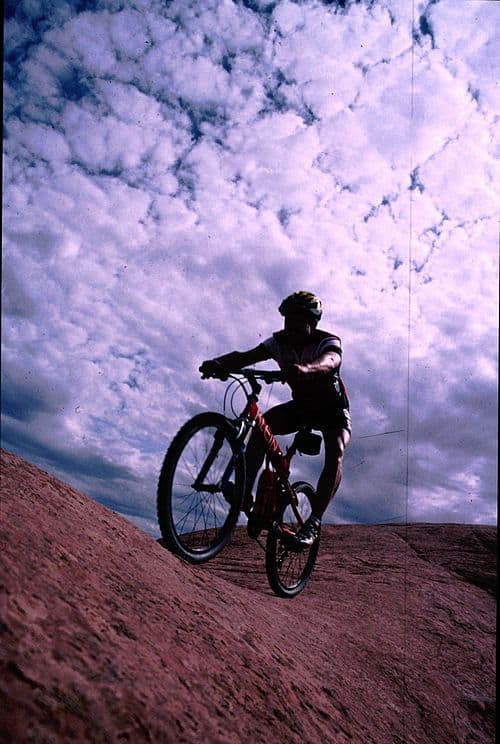

It’s true. Mountain biking is one of the most exciting, gut-checking, adrenaline-pumping sports there is. It requires skill, finesse, courage and physical strength. At Moab it also requires a comfortable familiarity with pain, a friendly association with contusions, a nodding acquaintance with exhaustion, and a willingness to get cozy with nausea and dehydration.

I tried to explain all this to my wife, but I think she didn’t hear me. I tried to sum it concisely by saying, “This is going to kick your butt.” But she didn’t seem to comprehend the meaning of “kick” and “butt” in this context. Later, she claimed I’d tricked her into one of the most miserable experiences of her life.

Okay, maybe I should’ve started her on something a little less arduous than Moab, arguably the nation’s most demanding mountain biking terrain. But I figured the experience would challenge her, bring her up to speed quickly, much like skiing the Rockies gets you better faster at skiing than, say, skiing Wisconsin.

Why Helicopter Rescues Are a Bad Thing

We arrived in Moab and checked into our lodging, the quaint and lovely Dream Keeper Inn (110 South 200 East). That night we dined at Buck’s Grill House (1393 North Highway 191), supping on buffalo meat loaf and elk stew, packing protein for the physical demands of the next day.

In the morning we rolled out of bed at 5am and made our way to Posion Spider Bike Shop (497 North Main Street). We had to get up early so we could get in three hours of mountain biking before the afternoon sun became so brutal it would take the mustard out of us.

We rented our bikes and met our van driver, a chatty, nonchalant young woman, possessing the careless, offhanded attitude so prevalent among young people who think nothing of plunging off a six foot cliff on a bicycle or peddling up a steep rock embankment for three hours in the blazing sun.

As we drove out to the trail head, she advised us not to do anything that would require immediate medical attention because it would be almost impossible for rescue teams to reach us without a helicopter. “And that costs a lot of money,” she added, picking absently at a scab on her elbow.

A Few Things That Can Kill You

We parked at the end of a long dirt road where we met our mountain biking guides from Rim Tours (1233 S. Highway 191). They went about checking the water and the packs and getting the bikes ready while another van load of cyclists pulled up.

We made our greetings and stood around chatting. A conversation ensued about scorpions and snakes and other small inconspicuous creatures that can dart out and inject you with a venom that can kill you. My wife gave me an uneasy look.

I was about to tell her not to worry when one of the guides started expounding on the dangers of getting separated from the group. “This area has of the highest incidence of search and rescue in the Utah,” he explained. “If you do get separated from the group, stay put, conserve energy and carefully nurse your water supply. Look, it won’t help if we find you and you’ve already died from dehydration.” He gave us a wink and a grin that elicited a nervous chuckle from the group. My wife narrowed her eyes at me.

We mounted our bikes and started peddling. We followed a modestly rough double track with a few short sand digs for just over a mile. It struck me as easy. I had mountain biked quite a bit when I was younger, rock hopping in Southern California, plunging through dense forest in West Virginia, slogging through mud flats in western Kentucky. But this was different. I had never ridden in the desert before, and I was a lot older now.

Flirting with Extinction

When we reached the smooth-surfaced, interleaved sandstone shelves known as slick rock the climb began in earnest, ascending more than 500 feet in a little more than two miles. As we worked the gears, the desert sun rose relentlessly in the sky. The temperature soared. Perspiration began to drip into our eyes.

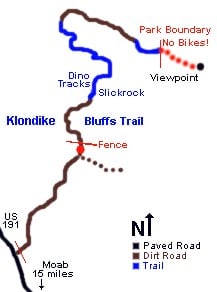

Klondike Bluffs Trail is considered a good entry level trail for Moab. It’s 9.6 miles round trip with a one mile hike to a scenic spot overlooking neighboring Arches National Park. It’s not supposed to be particularly hard and it probably wouldn’t have been if I hadn’t gotten a little too cocky.

We stopped to inspect some dinosaur tracks left by an enormous creature who had roamed these parts 8 million years ago. We were invited to reflect on the fact that the dinosaurs were secure in their dominance of the planet until a sudden cataclysm wiped them out. “They couldn’t have seen it coming,” remarked the guide.

As we turned our bikes to ride on, I noticed that a small contingent had ridden ahead to a place where two mounds of slick rock folded together to form a cleavage. A pair of cyclists were taking turns jumping across the gap. This was my opportunity to demonstrate my prowess.

Riding up quickly, displaying a certain insouciance, I missed the warning not to jump too early. I jumped too early. My front wheel came down in the gap. The handle bars plunged. My legs went straight up in the air. For a brief moment I was vertical, holding the handle bars, elbows locked, looking back through my outstretched arms at the astonished faces behind me. Then I slammed down hard on my back.

My head was swimming. I was sorting through my thoughts, trying to remember the last time I had had the air knocked completely out of me, probably some time during the Carter administration.

I got to my feet and tried to shake it off, tried to show them I was all right. But I couldn’t speak; there was no air to form words. I gasped, gulping oxygen like a dinosaur doomed by a cloud of dust. I sat down. Several people brought me water. It took me a moment to register the horrified look on my poor wife’s face.

I was woozy, but I assured her I was all right. I was an experienced mountain biker. This came with the territory. My wife, on the other hand, appeared undone. She thought maybe we should call it a day. She thought perhaps we were too old for this. I told her not to be silly.

Dr. Seuss Shaped World

We got back on the bikes and climbed for another half hour. At every bounce and bump my body ached. The sun rose higher in the sky. The heat began radiating off the rocks. The saliva felt glue-like in my mouth. It tasted of dirt and blood and a strange steely taste from deep down in my lungs.

My wife stopped frequently to drink from her water bottle and kept insisting that I do the same, but I have never required the copious amounts of hydration my wife requires. After awhile, I began to refuse her and urged her to keep moving, lest we fall behind the group, which was disappearing around the bend on the trail ahead. This annoyed her and she flashed back that she would not be prevented from taking water when she needed to.

At the turn-around point we left the bikes and tromped up a steep ascent to a stunning vista. Stretching out for miles in every direction was a red and gold desert studded with rock formations of every kind: chimneys of stacked boulders, spires of knurled stone, arches and prows and monoliths, a Seuss-ian world shaped by thousands of years of erosion.

On the hike back to the bikes I told my wife that, while the view was certainly worth the trip, the best was yet to come. “Now we get to ride downhill!”

She gave me a weary, put-upon look.

You Have to “Attack it!”

Mountain biking is a trade off. You endure a grueling uphill climb in order to enjoy an exhilarating downhill plunge. Like skiing, mountain biking requires the attainment of adequate speed to keep you moving over – rather than painstakingly picking through – various obstacles. This is essentially the challenge of it. You have to push your way past your comfort zone to get to a place where you can manage things adroitly.

The heat was building and my wife was flushing red. She stopped to mop her brow and said she wished this was over with. I told her to increase her speed, that she was going about things too tentatively. “You have to attack it!” I told her. “Faster. Or this will take all day.”

She told me to leave her alone.

I decided to ride on ahead for a bit, get my speed up, and wait for her and the others to catch up, or ride back to them, if need be. I zoomed down and stopped. I was suddenly light-headed. I got off my bike and stood there, woozy, trying to gather myself. It was hotter than hell. I belted down some water. I tried to walk it off. This would not be good, I told myself, if I were to pass out up here.

I waited for the others to catch up, hunched over, head between my knees, feeling nauseous. resolved not to say anything. It would not do for me to cause alarm, not in a situation where really nothing could be done. All I could do was take water and get down off the baking rocks as soon as possible.

But my wife was coming along agonizingly slow, stiff arming the handle bars, frightened and exhausted. I tried to explain that the whole thing was counter-intuitive, that in order to feel more in control she needed to speed up, not slow down. She told me to get away from her.

A Startling Announcement and a Shocking Discovery

I remained where I was and let them ride on. My plan was to let them get ten minutes out in front of me, and then ride down and pass them, whereupon I would wait for them again, and let them pass, and then catch up again.

This would involve long stretches of sitting idly in the sun, nursing my dwindling water supply, fighting the urge to pass out. But it was better than tottering along on the bike, trying to maintain balance while going the slowest speed possible, feeling every ache and pain with every bump, all while the sun was hammering down.

I implemented my plan and passed my wife a couple of times when, on the third pass, she finally decided to pick up the pace. As I pulled even with her, she bolted ahead and I actually stopped to admire her gumption. Then her wheels slid out from under her and she went down hard. Fearing the worst, I raced down, but when I tried to stop, the bike skidded out, caught in a rut, and flung me over on my side. I tumbled a few yards and fetched up against a boulder.

By the time I picked myself up and hobbled over to her, she was sitting on the ground, legs splayed in front of her, cradling her wrist, crying like a baby. I tried to comfort her but she snapped at me not to touch her. A couple of guides came over to check on her. When she finally pulled herself together she announced that she would not be getting back on the bike.

I was taken aback. I told her that walking was not an option. It was nearly noon. The sun was reaching its apex in the sky. The temperature was hovering around 100 degrees. There was still more than a mile to go and she didn’t have enough water for a long stroll in the desert.

She dug in. She accused me of doing this to her. She said she would rather perish in the desert than ever get on a mountain bike again. I stood there stunned, bleeding and parched. In a fit of pique I stalked away and was about to plop down on the ground and inspect my wounds when another cyclist advised me not to do that. He point at the spot where I was about to sit. A crustacean-like creature with a curling tail and pincers was occupying the spot. I recoiled in horror. The last thing I needed now was to be stung by a scorpion.

The Art of Getting Out of Bed

One of the guides suggested we should walk along with her. I got him aside and explained my situation. I feared I could not endure a mile long hike; I was battered and dehydrated and flirting with passing out. I needed to get down. He agreed. He urged me to get down as soon as possible and assigned another guide to ride along with me.

When we got back to the van, my companion grabbed some extra water and rode back to help with my wife. Soon the other cyclists started filtering in. Before long we were all assembled, waiting anxiously for the return of my wife and the two guides accompanying her. The sun was beating down like a hammer on an anvil. We all drooped in the heat, seeking the shelter of the shadow of the van. The minutes ticked on… and on.

Finally, my wife appeared, ambling along, chatting amiably with her companions.

“Are you all right?” I asked, rushing out to meet her.

“I’m better now,” she allowed. “But that really hurt.” She showed me her wrist, which was swollen. “I think I might have broken it.”

That night we lay in the bed, bruised, battered and groaning like a pair of wounded soldiers. The next morning I literally could not move. It took me twenty minutes to struggle up into a sitting position. I was a patchwork of scrapes, cuts and bruises. My wife’s wrist was puffy and red. We debated the merits of going to the hospital and decided against it. It took me till afternoon to get out of bed. Walking brought a symphony of pain. But eventually I began to recover. My wife’s wrist was not broken. No permanent damage was done.

So we survived our mountain biking trip to Moab. It was memorable but it wasn’t something we would be doing together again any time soon. To her profound disappointment wife had discovered what I had been trying to tell her. Mountain biking can kick your butt. It’s a grueling sport that requires fitness, know-how and courage. If you don’t prepare properly, know the terrain and stay within your limits, it will deal you a stunning blow, especially at Moab, where if you get caught on a hot day with too much bravado and not enough sense, you will find that your mounting biking days are numbered – that, in fact, they have gone the way of the dinosaurs.

Check it out…

Rim Tours

1233 S. Highway 191

Moab, UT 84532

(800) 626-7335 or at www.rimtours.com

Poison Spider Bike Shop

497 North Main Street

Moab, UT 84532

(800) 635-1792 or at http://poisonspiderbicycles.com

Klondike Bluffs Trail

21 miles north of Moab

Trail map and description at

Discover Moab.com

Dream Keeper Inn

110 South 200 East

Moab, Utah 84532

(888) 429-8112 or at Dream Keeper Inn

Buck’s Grill House

1393 North Highway 191

Moab, UT 84532

(435) 259-2051 or www.bucksgrillhouse.com

Previous stop on the odyssey: Area 51, Nevada //

Next stop on the odyssey: Canon City, CO

Image Credits:

This is Going to Kick, Jonathan Thorne; Cali Cochitta B&B, Dream Keeper Inn; Scorpion, Public Domain; Klondike Bluffs Trail, Utahmountainbiking.com; Dinosaur Footprint, Public Domain; A Seuss-ian world, Malcolm Logan; You have to attack it, Christof Berger; Sitting and Waiting, Jeff Wilcox ; Getting Down, ACP; Riding Rock, Tim Brink; Banged up, Josh Dibendetto; Bleeding, Cyclewreck.net