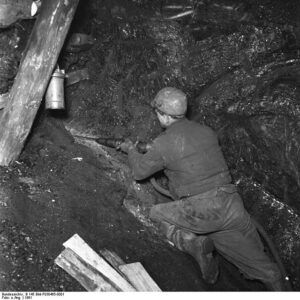

At around 3:25pm on April 5, 2010 Rex Mullins and Nick McCroskey were working 1000 feet underground at the Upper Big Branch Mine in Montcoal, West Virginia. Mullins, a 50 year old mining veteran, was working with McCroskey, a 26 year old graduate of Bluefield College, on the shearer of a 100 ton longwall mining machine. The machine, designed to cut into a coal seam with 60 rapidly rotating cutting picks, began to throw sparks.

Mullins and McCroskey were probably not overly concerned at first. Sparks are a common occurrence in mining. But when they realized that the machine’s water sprayer system was not working, they might have become alarmed. A moment later the sparks ignited a small fireball of methane gas.

Even this was not unheard of. Methane gas is a common byproduct of coal mining, and small, controlled explosions of methane sometimes occur. In properly managed mines such explosions are mitigated by proper ventilation and functioning water sprayer systems. Yet Mullins and McCroskey were not working in a properly managed mine, and they knew it. So they ran.

Unionization in the nation’s coal industry is down nearly a third from a decade ago. Today’s miners have to rely on the company to treat them fairly.

Paying with Their Lives in the Mines

Both Mullins and McCroskey were no doubt keenly aware of the high concentrations of coal dust in the mine. Coal dust can ignite if not properly safeguarded against. Standard procedure is to coat the dust with pulverized limestone, but, in the case of the Upper Big Branch mine, that was not done.

The sparks ignited the methane which touched off the coal dust. A tremendous fireball ripped through the mine, killing Mullins and McCroskey and twenty others.

Some weeks later, a lawsuit by one of the widows of the dead miners alleged that seven more miners might have survived had rescuers been able to reach them in time. According to the suit, when a would-be rescuer struggled to place emergency breathing devices on the seven injured miners, he became overwhelmed and ran for help. Coming upon a group of Upper Big Branch executives, he begged for their assistance but was refused. The seven miners died, bringing the death toll to 29.

The executives in charge of the Upper Big Branch mine had a lot to answer for. Mine safety violations are the responsibility of the mine operators. Following a year long investigation, a hard hitting report confirmed what many in the area already knew. The responsibility for the mine disaster belonged to the company and its executives.

Experienced coal miners are greatly in demand. An experienced miner can command six figures plus benefits.

In a report shocking for its candor the investigators pronounced, “A company that was a towering presence in the Appalachian coal fields operated its mines in a profoundly reckless manner, and 29 coal miners paid with their lives for the corporate risk taking.”

These days it is rare indeed for governmental authority to condemn corporate wrongdoing with such fervor. The more common approach is to downplay the transgression in an attempt to give the company a chance to line up its defense, lessen the legal consequences and dampen the public outcry. But here a government sponsored inquiry was pinning the blame squarely on the mine’s executives. Why?

Where’s the Outrage?

A front yard memorial near Beckley, WV. Oddly the name of the deceased is Massey, the name of the company responsible.

At the Lost Parrot Beach Bar & Grill in Beckley, WV a band was playing George Thoroughgood’s “Bad to the Bone”. Like many in the bar, two of the band members were wearing T-shirts supportive of the West Virginia Coal Association (WVCA). They were printed with the words: Friends of Coal.

The WVCA is not a union. In fact, unionization in the nation’s coal industry is down nearly a third from a decade ago and represents only 20% of coal miners. The WVCA is a trade association. Its members are the mining companies. One of its stated goals is “To be a strong advocate for improving safety at our members operations.”

On February 8th of 2011, ten months after the disaster at the Upper Big Branch mine, the WVCA awarded three Massey Energy Company operations the Mountaineer Guardian Award, an award presented to companies “that exemplify safety throughout West Virginia.” Massey Energy was the company responsible for the disaster at the Upper Big Branch Mine.

Yet not a few people among the many working class types at the Lost Parrot Bar & Grill were wearing WVCA T-shirts. Beckley is a small city. In all likelihood these were some of the same people who had lost friends and family in the Upper Big Branch Mine. I didn’t get it. Where was the outrage?

How to Get Rich with a High School Diploma

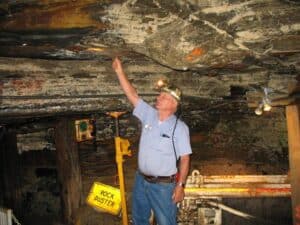

A trip down into the Exhibition Coal Mine costs $20 and is guided by a veteran miner who entertains as he enlightens.

Beckley, West Virginia is a town of 17,000 people. To call it a city is perhaps too generous. Yet to the citizens of the dozens of tiny mining communities in the surrounding mountains, Beckley is a metropolis. With an airport, two universities, a Walmart Supercenter and a Hooters, it’s easily the most vibrant town in the region. It’s also home to the area’s only bona fide tourist attraction, The Beckley Exhibition Coal Mine.

The Exhibition Coal Mine opened in 1960 and has added some interesting new features in recent years, including a restored company town and a 14,000 sq ft visitor’s center. A trip down into the mine aboard a rattling rail car costs $20 and is guided by a veteran miner who entertains you as he enlightens you about interesting aspects of coal mining. The Exhibition Coal Mine is sponsored by the WVCA.

Over the course of the tour our guide pointed out a coal seam and familiarized us with various illumination methods.

Over the course of the 45 minute tour our friendly guide pointed out a coal seam and familiarized us with various illumination methods. He educated us about how miners can tell if their oxygen is being depleted and treated us to the obligatory turning off of the lights, a staple of every underground tour. He also managed to get in a few timely quips and win us all over with his honesty, authenticity and charm. But the most interesting thing he said was that experienced coal miners are greatly in demand these days. An experienced coal miner can make six figures and get good benefits. All this can be had with nothing more than a high school diploma.

The mines are desperate for good miners, and not because no one is applying, but because the turnover is so high. The majority of hires don’t last out the year. The work is physically demanding and miners are expected to be punctual and dedicated.

“It’s the drugs,” our guide lamented. “So many young people are into drugs these days.”

In Bed with the Wrong People

The drive up to the Upper Big Branch Mine is a lovely trek up curvy mountain roads through cascading mountain greenery.

But what our friendly guide didn’t tell us was that another deterrent was likely keeping miners from remaining at their jobs, something just as insidious as drugs.

In West Virginia a coal miner’s dedication to his employer can sometimes be expected to extend to a tacit disregard for safety. Mine regulations are viewed by the companies as government overreach and are routinely flouted. That was certainly the case with Massey Energy, as investigations into the disaster at the Upper Big Branch Mine have brought to light. Massey Energy kept two sets of books. In their production log they recorded ongoing problems with coal dust accumulation, ventilation issues and equipment malfunctions. But that’s not what they showed the Mine Safety

Health Administration (MSHA), the agency in charge of regulating mine safety. What’s more, Massey Executives pressured employees not to record hazards, and miners feared being fired if they objected.

In other words, miners working for Massey were expected to endanger their own lives and keep quiet about it. It’s no wonder the turnover among coal miners is high.

Still in all, shouldn’t the MSHA have been able to detect that something was amiss? After all, they are professional inspectors whose duty is to ferret out mine safety violations. Were they really that blind? Or like the SEC ahead of the subprime mortgage crisis, was the MSHA in bed with the very people it was supposed to be policing?

The Incompetent and the Corrupt

At the Upper Big Branch mine waste conveyers and shaft towers present a bleak industrial visage against a background of lush green mountains.

According to a 1998 article in the Louisville Courier Journal, “A web of social connections binds inspectors and coal operators in small towns. Foremen and inspectors see each other at church and at high school sporting events. Many inspectors and foremen once worked together as miners. Some are related.” In fact, it’s not unheard of for mine operators to be warned of an inspection ahead of time. According to the same article, “Inspectors’ visits are supposed to be unannounced, but mine operators often are warned that inspectors are coming, giving them time to get dust controls working and avoid fines.”

And even after a mine has been cited for a violation, the push to ease regulations has made it extremely easy for them to contest the fine and tie up the case in a review committee for years. Few fines are ever enforced and mines are rarely closed.

So a coal miner working in unsafe conditions 1,000 feet underground has virtually no one to appeal to. Under these conditions, he has two choices. He can keep his mouth shut and hope nothing goes wrong, or he can quit.

But something did go wrong at the Upper Big Branch Mine, and the ensuing hue and cry made the MSHA look, if not corrupt, at least incompetent. Perhaps to avoid the appearance of culpability the agency pointed its finger at the mine operators and issued a report whose language was scathing, placing the blame squarely on them.

So now that we know who’s at fault, what ever happened to those big bad mine operators? Where are the Massey Executives responsible for this carnage? The answer may surprise you.

Doing Their Best to Forget

The entrance to the Upper Big Branch Mine is riddled with signs touting safety and stern warnings against trespassing.

The drive up to the Upper Big Branch Mine is a lovely trek up curvy mountain roads through cascading mountain greenery. Along the way you pass through small towns where the front porches of homes press right up against the roadway. Occasionally you pass through a former company town with a few boarded up storefronts and an abandoned railroad depot. The concept of the company town died in the 1930’s. With the advent of widespread automobile ownership, the lord and serf relationship of working for the all-powerful coal company faded away.

The main entrance to the Upper Big Branch Mine is riddled with signs touting safety and stern warnings against trespassing. Its waste conveyers and shaft towers present a bleak industrial visage against a background of lush green mountain tops. It is eerily silent now.

A half mile down the road at the ambulance entrance an impromptu memorial to the 29 dead miners sits at the base of a steel support tower. 29 black mining helmets hung atop 29 red crosses. An adjacent sign says, “We will never forget our UBB brothers.”

A half mile down the road an impromptu memorial to the 29 dead miners sits at the base of a steel support tower.

But in Abingdon, VA former executives of Massey Energy are likely doing their best to forget. About a dozen former execs have been hired by Alpha Natural Resources, a coal mine operator that absorbed Massey Energy in a friendly takeover. Speculation has it that as part of the takeover arrangement Alpha agreed to hire Massey executives and compensate them handsomely. Alpha denies the charge.

Nevertheless, Alpha came under intense scrutiny for its decision to place former Massey COO Chris Adkins in charge of implementing Alpha’s main safety program. The move drew such ire that Alpha withdrew its offer to hire Adkins and instead gave him an $11 million dollar departure package.

All together, the executive team named with responsibility for the Upper Big Branch Mine Disaster which killed 29 miners will receive $196 million in salary, benefits, severance, pension, retirement and deferred compensation from Alpha, according to published reports.

A Dirty Business

Back at the Lost Parrot Beach Bar & Grill in Beckley several patrons are wearing their West Virginia Coal Association T-shirts with pride. Friends of Coal, they say.

They are championing an industry with a sad record of safety violations and one that has recently handed out an award to a company that investigators have found responsible for the deaths of 29 miners. Why?

The best I can come up with is that West Virginia still retains the legacy of a company town. Although the towns themselves are gone, the mentality of owing everything to the all-powerful coal company lives on. In a world where the bosses routinely violate safety procedures, government inspectors turn a blind eye, and unions have virtually no clout, there’s no such thing as justice.

In a world where 29 miners are killed and the executives charged with responsibility are given awards and made into millionaires, there’s no percentage in stirring things up. Coal mining is a dirty business and if you’re not careful you could choke on it.

Better to wear the shirt and make nice. The only other option is to get out. Which may be why the industry is having trouble finding miners. A great pay check isn’t worth much if you’re dead.

Previous stop on the odyssey: Canton, OH //

Next stop on the odyssey: Orlando, FL

Sources:

Mine Safety in America, NPR on line, 30 June 2011, 29 July 2011.

In Memory of the Men of the Upper Big Branch Mine, Robert Byrd C. Byrd National Technology Transfer Center at Wheeling Jesuit University, Acquired 29 July 2011.

Find Law, Some Miners Survived Initial Massey Blast, LawInfo.com, 4 April 2011, 29 July 2011.

Statement by MSHA Assistant Secretary Joseph A. Main

on release of Upper Big Branch Independent Investigation Report, United States Department of Labor Mine Safety Health Administration, 19 May 2011, 28 July 2011.

Malloy, Daniel. Are Union Mines Safer? Pittsbugh Post Gazette.com, 18 April 2011, 22 July 2011.

Press release from Massey Energy, Massey Energy Operations Earn Mountaineer Guardian Award, PRNNewswire.com, 8 Feb 2011, 29 July 2011.

Hall, Mike. Federal Investigation Finds Two Sets of Books, AFL/CIO News Now Blog, WNY Labor Today, 30 June 2011, 29 July 2011.

Upper Big Branch Disaster – Feds: Mine Faked Reports, Associated Press, Bluefield Daily Telegraph, 30 June 2011, 22 July 2011.

Harris, Gardner. Ideal Conditions for Tests Taint Results, Dust, Deception and Death: Trying to Regulate the Mines, Louisville Courier-Journal, 20 April 1998, 29 July 2011.

What’s Next for Coal Mine Safety, OMB Report, 20 April 2010, 29 July 2011.

Berkes, Howard. Merged Company Tries to Retire Massey’s Legacy, NPR online, 2 June 2011, 28 July 2011.

Berkes, Howard. In Merger, Massey Mine Execs Would Get Top Jobs, NPR online, 16 April 2011, 28 July 2011.

Image Credits:

The fireball ignited, Public Domain; Coal miners, Public Domain; An experienced miner, Bundesarchive; Front yard memorial, Malcolm Logan; A trip down into the mine, Malcolm Logan; Our guide pointed out a seam, Malcolm Logan; The Drive up to the mine, Public Domain; The Upper Big Branch Mine, Malcolm Logan; Signs outside the mine, Malcolm Logan; Miner’s Memorial, Malcolm Logan; Company town, Public Domain.

3 comments

Could your helmet photo be used as a figure in the intro to a non commercial scholarly scientific publication? Thanks.

Yes, you may use my photo of the miner’s helmets in your publication.

Please, however, include a link back to the blog post here. Thanks.