Crime of the century? The words conjure up thoughts of a single shocking offense, a crime so appalling it stands out above all the others. But in fact, many crimes have been labeled as such. The O.J. Simpson case (1994), the Patty Hearst kidnapping (1974), the Manson murders (1969), and the Murder of the Black Dahlia (1947) to name a few.

The crime most associated with the term was the Lindbergh kidnapping. The press couldn’t get enough of splashing the words across headlines when the famous aviator’s baby was abducted and killed in East Amwell, New Jersey in 1932. But even that wasn’t the first time it was used.

Ten years earlier in nearby New Brunswick, New Jersey another crime shook the nation and earned the moniker, a crime largely forgotten today, the brutal slaying of a minister and his choir singer, the first crime of the century.

The Hall-Mills Murders

Curious sightseers descended on the murder scene, carrying away souvenirs and contaminating key evidence.

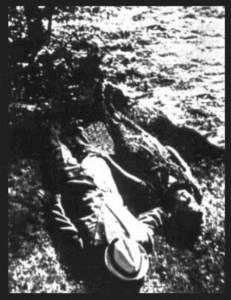

It all began on a summer day in September of 1922. A fifteen-year-old girl and her twenty-three-year-old consort were strolling down De Russey’s Lane, a secluded dirt road frequented by clandestine lovers, when they came upon the bodies of a man and a woman.

The bodies were lying on their backs with the woman’s head resting on the man’s arm. A Panama hat had been placed over the man’s face. The man had been shot once in the head. The woman had gotten it much worse. She had been shot three times in the face, and her throat had been cut from ear to ear. A .32 caliber cartridge case was lying nearby. Some torn pieces of paper were scattered over the bodies. A small calling card was left leaning against the man’s left foot. Clearly, the killers had posed the bodies to send a message.

When the torn pieces of paper were reassembled, they revealed a lover’s note. “There isn’t a man who could make me smile as you did today,” it read. “I know there are girls with more shapely bodies, but I do not care what they have. I have the greatest of all blessings, a noble man, deep, true, and eternal love.”

The calling card belonged to Reverend Edward W. Hall, the pastor of the Episcopal Church of St. John the Evangelist in New Brunswick. He was the dead man. The woman lying next to him was Eleanor Reinhardt Mills, one his choir singers.

The Suspects

From the beginnings the case had all the earmarks of a media sensation. A pillar of New Brunswick society, the Reverend Hall, had been caught in a lover’s tryst with a lowly choir girl. Both were married. They had been conducting their affair openly. Many people knew about it. Their behavior had been scandalous, and now they were dead, murdered. Brutally.

It was lurid stuff, and the newspaper reading public gobbled it up. Curious sightseers descended on the murder site in droves, contaminating or carrying away key evidence. Investigators were at their wits’ end and nothing seemed to make sense. Except one thing, the most obvious thing of all. Jealousy.

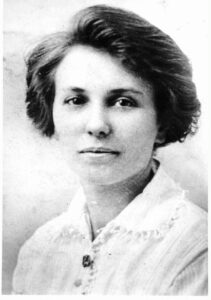

If the story wasn’t juicy enough already, Reverend Hall happened to be married to Francis Stevens Hall, the only daughter of one New Brunswick’s most prominent families and a doyen of New Brunswick society.

By virtue of her social standing, Mrs. Hall was considered the kind of person whose wealth and influence could be used to make a cheating spouse pay dearly for his philandering. In other words, she had the means and motive.

As for the choir singer’s husband, Jimmy Mills was considered a weak and servile individual and therefore unlikely to be a killer. In a mark of the offhanded prejudice that marked the case at every turn, investigators dismissed Jimmy Miller and concentrated on Mrs. Hall, who could more easily be seen as vindictive and domineering, even though there was nothing in her past that suggested she was.

Frances Hall lived in a mansion on fashionable Easton Avenue in New Brunswick along with her husband and her brother, an eccentric character named Willie Stevens. Willie enjoyed dressing up as a fireman and watching parades. He was considered weak minded by those who knew him.

The casual insensitivity of that assessment was common for the era. The tendency to label others with derogatory terms was pervasive in the 1920’s, a time of widespread bigotry, something that wouldn’t be understood as problematical until the Nazis murdered 6 million Jews and destroyed Europe behind a racist philosophy two decades later. Willie Steven’s presumed weak mindedness made him a suspect, a victim of his supposedly domineering sister, and it didn’t help that he owned a .32 caliber revolver.

The Star Witness

Prosecutors constructed a case alleging that Mrs. Hall, in a fit of jealousy, enlisted the aid of her brothers Willie Stevens and Henry Stevens as well as a cousin, Henry de la Bruyére Carpender, in the murder of her cheating husband. The case was weak. It was based on the testimony of a Somerset County pig farmer who claimed to have seen Mrs. Hall and her relatives commit the murders. Unfortunately, the pig farmer was the most unreliable of unreliable witnesses.

Mrs. Jane Gibson lived in a converted barn near the end of De Russey Lane. On the night of the murders she claimed she had heard a dog barking and, looking out her window, had seen the figure of a man leaving her cornfield. Thinking the man had been stealing her corn, she mounted her mule and followed him. After riding some way down De Russey Lane, she heard voices and noticed what looked to be a group of people quarreling in a clearing. Then she heard a gunshot and one of the figures fell to the ground. Frightened, she pulled her mule around and rode away, after which she heard several more shots.

St John the Evangelist Episcopal church today. The minister and the choir singer began their affair here.

Mrs. Gibson’s story conflicted with the autopsy report. What’s more, every time she spoke to investigators her story became more embellished, often in line with newly revealed facts. She sometimes contradicted herself and came late to the assertion that it was Mrs. Hall she had seen in the clearing. When she spoke to the press, she bristled at the suggestion that she was making things up. Most damning, her daughter had gone on the record saying she was a chronic liar and not to be trusted. But the prosecution had little else to go on, so they embraced her as their star witness.

The press loved her. She was a caricature of a hard-shelled country bumpkin, something they thought would appeal to the prejudices of readers and sell newspapers. They labeled her The Pig Woman and played up her story. It worked. Newspapers flew off the shelves.

But it did nothing to solve the murders. In the end, a grand jury refused to believe her testimony, and Mrs. Hall was set free. It appeared the case had hit a dead end.

The Press

In recent decades the influence of the media on the execution of justice was most depressingly seen in the trial of O.J. Simpson trial, an unmitigated media circus. To a greater or lesser extent, each of the so-called crimes of the century were influenced by the media. But in 1922 the power and reach of the newspapers was something new and unprecedented.

In the early years of the 20th century, William Randolph Hearst along with his rival Joseph Pulitzer had taken the scandal sheets mainstream and created tabloid journalism, a style of journalism that plays fast and loose with the facts in order to build a compelling narrative. Today, the public ought to be able to tell when they’re being manipulated by the media, and they still can’t do it. In the 1920’s they didn’t have a chance.

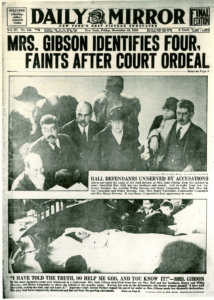

Hearst bought the New York Daily Mirror in 1924 with the object of increasing its circulation. As it happened, a year and a half had passed since a grand jury had failed to indict Mrs. Hall based on the dubious testimony of The Pig Lady, and the case had gone cold. But Hearst knew a good story when he saw one and was determined to resurrect it.

Seizing on the testimony of the estranged husband of one Mrs. Hall’s servants, The Mirror reported that Mrs. Hall had bribed the servant to keep her quiet about Mrs. Hall’s whereabouts on the night of the murders. The Mirror demanded answers. Feeling mounting public pressure, the investigators went back to work.

The Indictments

In August 1926 Mrs. Hall and Willie Stevens were again arrested. Also taken into custody was Henry de la Bruyére Carpender and Henry Stevens. Facing a procession of tangential witnesses whose motives were easily called into question, the suspects sat through grueling grand jury testimony notable for its provocative revelations. This time the suspects were indicted and brought to trial.

The Mirror’s exertions had had the desired effect. Circulation shot up. Curious spectators once again descended on De Russey Lane. And the murders of the minister and choir singer were deemed the crime of the century.

The trial took place at the Somerville County Courthouse on November 3rd, 1926 amidst a carnival atmosphere. Crowds of spectators packed the courthouse lawn, the streets were lined with refreshment stands, performers entertained. Three hundred reporters from every major newspaper in the United States and Europe descended on the courthouse. Telephone and telegraph lines hung down the outside of the building like wire bunting. A New York radio station set up a live feed. Everything was in place for a sensational verdict. But it was not the verdict anyone wanted.

The Trial

One by one, the defense discredited the prosecution’s witnesses, even going so far as to question them about how much they had been paid by The Daily Mirror, something deemed irrelevant by the judge and passed over. Nevertheless, the wind had come out of the prosecution’s sails. In desperation they turned to their star witness once again.

By this time, however, Mrs. Gibson seemed to have grown weary of the whole charade and had taken to her bed with a mysterious illness, which, she said, precluded her from testifying. Undeterred, the prosecution arranged to have her brought into the courtroom while lying in bed. The bed was arranged to face the jury box, and the questioning began. Mrs. Gibson identified the suspects, then fainted in dramatic style. After she was brought back to full consciousness, the defense had their turn with her.

It didn’t take them long to expose her as a fraud. Seething with anger, she rose up on one elbow and pointed at the defendants. “I have told the truth so help me God, and you know it!” A faint smile appeared on Mrs. Hall’s face as The Pig Woman was carted away.

Then the defendants were called to the stand. They handled themselves well. Calm, measured and self-assured, they exuded confidence in their innocence. Only Willy Stevens threatened to be a liability for the defense. Spurred on by the Daily Mirror, the public couldn’t wait to hear from him. But he surprised them, turning out to be not at all the weak minded fool he had been portrayed as in the press, even getting off a clever gibe at the prosecution’s expense. In the end, all four were acquitted, and the circus was over. But the murders of the minister and the choir girl went unsolved, and remain so to this day.

The Disregarded Statement

Lost in all the testimony from dozens of witnesses over four long years was a statement from a Bound Brook chauffeur who reported seeing a small Ford on the side of Easton Avenue on the night of the murders. In the car were what appeared to be three “negroes”, although it was possible that they were white men wearing black face. The car had no license plates. Further on, the chauffeur saw another vehicle, again without license plates and men in it. On September 16th, after the bodies were found, the chauffeur reported what he had seen to the New Brunswick police. Curiously, his report was never acted on.

It was a question that needed answering. What would white men wearing black face be doing near the scene of the murders? And why would the report be brushed aside?

Men of Means and Reputation

In 1922 the Klu Klux Klan was widespread north of the Mason-Dixon line. Here is a Klan gathering in Ontario, Canada.

Racism and bigotry were common in the United States in 1922, and the most visible representative of that bigotry was the Klu Klux Klan. At the time, the organization was not the discredited pariah it is today. On the contrary, it was thriving. The Klan had more than a million members in 1922, and they were not confined to the south. As it happened, New Jersey had one of the highest concentrations of Klansmen north of the Mason-Dixon line.

In the northern part of the state most of its members were contained within the thirty mile area between Paterson and New Brunswick. Merchants and professionals made up its ranks, men of means and reputation, which included, undoubtedly, a few law enforcement officials. If a report implicating the Klan were received, it is perhaps no surprise it was swept under the rug. But why would the Klan have killed a white minister and his paramour?

Today the Klan is understood as a white supremacist organization whose main purpose is to promote the superiority of the white race. But in the 1920’s its main purpose was to police the morality of others, those it believed had lost touch with their Christian values. To the extent that the Klan regarded Blacks and Jews as subhuman, they too were in violation of Christian values and condemned. For whites it was a matter of correction.

The Morality Police

Taliban beating a woman in public. Intolerance for others is a mark of bigotry, which, when unchecked, often leads to violence.

Not unlike the religious police of the Taliban, the KKK took it upon themselves to enforce morality through coercion. Like all good Christians, they were hyper-focused on sexuality. Men and women who engaged in extramarital sex were in violation of the moral code and deserving of punishment.

Stripping, flogging, branding, and shaving heads were among the milder chastisements. Tarring and feathering, castration and rape were reserved for the worst offenders, and murder was not out of the question. An indiscreet liaison between a man of the cloth and one of his choir singers might well have been regarded as a transgression meriting the harshest of punishments.

Klan murders were ritualistic. They often posed the bodies after killings and left signs of their rationale. The way the minister and choir singer were found, lying side by side, her head on his arm, littered with the torn pieces of a love note was textbook Klan. The brutality of the killing was also a tip off. And the chauffeur’s report was not the only statement pointing to Klan involvement. Hours after the murders became known, prosecutors received a wave of letters and phone calls accusing the Klan. None were acted on.

A Dirty Little Secret

The bigotry and intolerance of America in the 1920’s was not unlike that of Nazi Germany during the same period.

As crimes of the century go, the Hall-Mills murders were groundbreaking. They were the first to be exploited by the tabloids, the first to provoke a media circus, the first to have a sex scandal at their core, and one of the few that were never solved. These distinctions have echoes in high profile crimes of later generations. Yet the Hall-Mills murders were unique.

What lurks behind the killings of the minister and the choir singer is a dirty little secret of America’s past, the commonplace bigotry of the time, the snickering disdain for the intellectually disabled, the intolerance of sexual freedom and the willingness to use violence to correct it, the murderous contempt for people of color and Jewish people, all the ways in which America was not unlike Nazi Germany, which was just emerging at the time.

The real crime of the century was what happened when that course was not corrected and 75 million people lost their lives in World War II. Fortunately for us here in America we saw the consequences and made adjustments before it was too late. And yet, but for the grace of God, there went we.

Imagine how reckless we were. Giving credence to demagogues, embracing grievance and outrage, excusing cruelty and lies, all in the name of correcting corruption, enforcing a narrow view of morality and making everything right. Thank God we learned our lesson.

At least we’ll never make that mistake again.

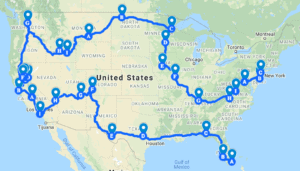

Previous Stop on the Odyssey: Ghost Towns of New Jersey

Next Stop on the Odyssey: New York, NY

My American Odyssey Route Map

Sources

Kunstler, William M. The Hall-Mills Murder Case: The Minister and the Choir Singer. Rutgers University Press, 1964.

Image credits

Inspecting the bodies, Public domain

Hall-Mills bodies, nursemyra.com

Sightseers at the murder scene, New Brunswick Free Library

Frances Stevens Hall, University of Rutgers Press

Willie Smith, Public domain

Hall mansion today, Malcolm Logan

St John the Baptist Episcopal church, Malcolm Logan

Reverend Edward Wheeler Hall, Public domain

Eleanor Reinhardt Mills, Public domain

Somerset County Courthouse, Malcolm Logan

The Pig Woman in the courtroom, weirdnj.com

Daily Mirror headlines, Public domain

De Russey Lane in 1922, Public domain

Klu Klux Klan in Ontario, Public domain

The Talian beating a woman, RAWA CC-BY-3.0

Hitler’s Mein Kampf, Public domain