About two hours of hiking on a moderately inclined trail. This was going to be a piece of cake. Right.

Here’s a tip for any would-be hikers out there. Don’t trust the Internet.

The trouble is anyone can post anything on the Internet, and if it meets the criteria of Google’s algorithm it can be driven to the top of the search engine rankings, laying in wait like a coiled snake, ready to strike the first foolish boob who types in something harmless like, “Great hiking in New Hampshire.”

I got Tuckerman Ravine Trail, described as “one of the shortest, most scenic, and most popular trails to the summit” of Mt. Washington. Short, scenic, popular. In my mind that translated to, “About two hours of hiking on a moderately inclined trail accompanied by lots of people walking their dogs.” And only 4.2 miles! This was going to be a piece of cake.

Right.

At 6,288 feet Mt. Washington is the highest point in the northeastern United States. And it boasts the worst weather in the nation.

Overkill?

Here are some things you should know about Mt. Washington before heading out on this leisurely hike. At 6,288 feet Mt. Washington, New Hampshire is the highest point in the northeastern United States. After the first two miles, the Tuckerman Ravine Trail suddenly gains in elevation about 3,000 feet, taking you from a brisk amble to rigorous hand-over-hand climbing across a treacherous boulder-strewn landscape. At its summit, Mt. Washington boasts the worst weather in the United States with recorded wind speeds of 231 mph, and it’s bitterly cold. The temperature difference between base and summit often exceeds 40 degrees.

I headed out in a T-shirt and cargo shorts with a single bottle of water tucked into a side pocket. I should’ve known something was amiss when I saw other hikers hefting alloy frame hydration packs and fitting goggles onto their faces. But let’s face it, people overdo it. How many suburban moms drive SUVs to the supermarket? SUVs designed to conquer Mt. McKinley. Overkill, I thought. Conspicuous consumption. I was wrong.

Top Ten Deadliest

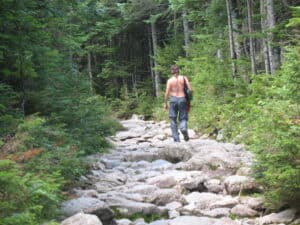

In the beginning there was nothing to it. The trail wound along through a pretty woodland featuring closely set spruce and balsam fir. It was 83 degrees and the sun was shining.

View across a pond near the halfway point to the bowl of Tuckerman Ravine. Click any picture to enlarge.

About ten minutes in I could hear the rush and tumble of the Cutler River and just beyond that the trees parted to reveal a two-tiered cascade, the first chute dumping into a frenetic stream which passed under a foot bridge and plunged down to the second. Nice, I thought. Lovely. I saw a man walking his dog.

Further on, the character of the trail began to morph. What had been a dirt path intermittently strewn with rocks became a rock path here and there laced with dirt. Then it became all rocks. But these rocks were manageable for anyone with a spring in his step, about the size of throw pillows, scattered helter-skelter. Nothing to it. I kept going.

Temperatures at the peak of Mt. Washington can descend to -50 degrees farenheit. It snows year round here.

I had scheduled three hours for this hike and fully expected to summit in 90 minutes. I was in good physical shape, well rested, and game. I had hiked mountains higher than this many times and considered the overwrought way other hikers had geared up for it laughable – so much gear!

Little did I know that I was climbing one of the 10 most dangerous mountains in the world, ranked right up there with Everest, Denali and K2.

The website GearJunkie.com has this to say about Mt. Washington:

Even in 1860, climbing Mt. Washington was considered quite a feat. Here a man stands at the summit looking north.

To experience a killer mountain a little closer to home, look no further than this New Hampshire peak. The rapidly shifting weather, hurricane force winds, and summer ice pellets scouring this slope have claimed more than 100 lives. Temperatures at the peak can descend to -50 degrees Farenheit. In fact, the strongest wind gust ever measured on Earth was recorded on this peak, a gale of 231 mph.

I stopped to take a sip of water and check my fingernails. They were getting a little long. I was going to have to clip them when I got back. I kept going.

The Place of the Storm Spirit

The Indians called it “the place of the storm spirit” and dared not ascend it. Europeans, however, felt no such compunction and in 1642 an Irish ferry pilot named Darby Field made the first ascent. Others came after him. In 1784 the mountain got its name, nestled in the so called Presidential range it was deemed Mt. Washington and stood preeminent among its neighbors, Mt. Adams, Mt. Jefferson and Mt. Monroe.

Frigid winds from the north careen through these peaks, colliding with moist weather systems from the Atlantic coast and dying storm tracks from gulf, making for a potent stew. Winds exceeding hurricane force occur an average of 110 days per year. Snowfalls at the summit occur year round, even in July and August.

Perhaps it was this novelty that drew Ethan Allen Crawford to the summit in 1826 where he built a house, which lasted five years before a storm blew it apart. Most importantly, Crawford also laid out a bridle path to the summit, which became the first mountain hiking trail in the United States. Being an avid hiker and student of history, I was on hallowed ground. But I didn’t know it. I was just heading along, oblivious.

Malcolm Logan at The Headwall of Tuckerman Ravine on Mt. Washington, NH. I thought I was almost finished. But I was just getting started.

The rock strewn trail was slow-going but manageable. I caught up and passed several other hikers. For me, hiking is a form of exercise and I like to get after it. I don’t do a lot of standing around, communing with nature. On Mt. Washington, hiking along through dappled sunlight, passing through corridors of paper birch and mountain ash, my blood was up and I was perspiring. I hardly noticed that the temperature was falling.

From Hiking to Climbing

At the halfway point there’s a small hiker’s store and a hand pump for drawing water. I could’ve stopped and replenished my supply, but I blew it off. I was making good time, and I had six ounces left in the bottle. At this pace, I would be on top of the mountain in another 45 minutes.

Right after the halfway point, however, the character of the trail changes. It becomes narrower and rockier. At points it heaves upward in 45-degree pitches of seven feet or more, requiring careful hand-over-hand climbing. As I made my way along, these intervals became longer and more frequent until I was passing winded hikers, standing off to one side, mopping their brows and drinking hungrily from their bottles.

The trail wound along to the base of The Headwall and then headed up at a precipitous angle, ascending through a narrow tumble of rock. This is the view looking back.

After about an hour of this, the trail flattened out and passed through an alpine meadow girding the brow of an immense glacial cirque. In the near distance stood a mighty granite amphitheater down which spilled two slender waterfalls. This is known as The Headwall, the 1,850 foot bowl of Tuckerman Ravine.

The trail wound along to the base of The Headwall and then headed up at a precipitous angle, ascending through a narrow tumble of rock, slick with the mist of the waterfalls. Each step and handhold needed to be considered before being initiated. What had started out as hiking had turned into climbing.

Now the perspiration formed rivulets that traced down my brow. My breath came in snatches. I kept on. An hour passed.

Looking back, I could take in the whole vast expanse of the valley. It was stunning, laid out in the late morning sunlight.

Above the Tree Line

Interspersed among the rocks were patches of arctic sedge and wildflowers. As I carried on, these punctuations of green became less frequent until the dominant feature was rock.

But the good news was that I was now above the tree line. Looking back, I could take in the whole vast expanse of the valley. It was stunning, yes, laid out in the late morning sunlight. But now I noticed fog tumbling over the edge of the escarpment and felt the wind picking up. Still, I was almost to the top. I had surmounted The Headwall, how much further could it possibly be?

Looking ahead, I saw a measureless landscape of tumbled boulders, a spilled-out jumble of craggy blocks that disappeared gradually into the fog. I kept going.

Now I noticed fog tumbling over the edge of the escarpment and felt the wind picking up. It started getting colder.

Panic

The grade was no longer the problem. The climbing here was not upward, but over. Imagine yourself in an automobile graveyard with cars spilled helter-skelter against each other in a random sprawl across hundreds of acres. You would have to clamber over them to get from one side to the other. This was what it was like. The analogy fails, however, when you consider that cars come in different models. These boulders were all pretty much the same gray-green hulks of coarse-grained schist and quartzite. You could easily lose your bearings and get lost among them, wandering off the trail.

Ahead I saw a measureless landscape of tumbled boulders, a spilled-out jumble of craggy blocks that disappeared gradually into the fog.

Below the tree line, the trail had been marked with painted blazes on trees and rocks. Here a painted blaze would be difficult to detect, so the Forest Service has erected cairns, stacks of stones, to mark the trail and keep hikers from wandering off a cliff. Nevertheless, the monotony of the landscape combined with the thickening fog made it difficult to stay on course. At one point, after picking my way painstakingly through the rocks for awhile, I looked up to find no cairns. A moment of panic set in. Where in the hell was I?

Finally, way off in the distance, I glimpsed a cairn through a skein of fog. I kept a bead on it as I made my way back to the trail.

“I Hope You Have a Jacket”

The Forest Service had erected cairns, stacks of stones, to mark the trail. Still, it was easy to get lost.

Now I saw a pair of hikers coming down from the top. This was a good sign. I was getting close, and it was a good thing, too, because I was getting tired. I stopped to catch my breath and ask them how much further it was when one of them stopped and looked me over like I had lost my mind. He said, “I hope you have a jacket. It’s 43 degrees up there and the wind is blowing like hell.”

I was wearing a T-shirt and shorts. I was damp with sweat. I didn’t answer him. He shook his head dolefully and carried on.

For the first time I noticed how cold it had gotten. I could see my breath. I hadn’t gotten too chilled before now because I’d been working so hard, but now it occurred to me that I’d better keep pushing myself or my body temperature would plummet, and then I’d be in real trouble.

When was this going to end? Where was the top? I’d been out here for hours now. My muscles ached. My legs felt rubbery. And the monotony. A giant step up, knee up above the belt line, pitching forward, taking a handhold, hauling myself up and over a boulder, and then again – and again – and again. Picking out a spot a hundred yards up, barely discernible in the fog, making my way arduously to it, and then looking ahead to find still more of the same. Over and over. And the temperature kept falling, and the wind picked up. I didn’t realize it at the time, but at any moment, even in summer, a snow storm could blow in, covering the rocks, making the footing treacherous. A person could slip and fall, die of exposure. It all depended on the fickle mood of the storm spirit.

Talking in Feet, Not Yards

Another pair of hikers came down. People hiked in pairs around here. Great idea. I asked them how much further it was. “About 2000 feet.”

Typical, I thought. These guys talk in feet, like mountain climbers. I had to do the math in my head, because I think in terms of yards, like a guy who sits in a recliner and watches football games. That’s about 600 yards. I had to go the length of six football fields to get to the top. Six more football fields of this grueling moonscape. I pressed on, only because going back was more frightening than going forward.

Final steps leading to the summit of Mt. Washington. It was 43 degrees up here. 87 degrees down below.

Close to an hour later, I overtook another hiker, a young woman, panting and struggling through the rocks. We stopped to talk. “How much further do you think?” I asked.

She pointed ahead. “I don’t know,” she said. “But my boyfriend’s up there and he says it’s not too far.”

I looked to where she was pointing, and I could just make out his figure, a vague silhouette in the fog. He was waving back at us, yelling something. She was leaning forward, listening. “He says there’s a car.”

“Huh?”

“He says there’s a car up there.”

Well, I thought. That’s probably a good sign. We carried on, and a few minutes later, we hauled ourselves over a rocky lip and found ourselves standing in a parking lot.

Malcolm Logan at the summit of Mt. Washington. I touched the sign and hurried inside before pneumonia set in.

The Summit

I couldn’t believe my eyes. “There’s a road up here?”

“Yep,” she said. “And the rest of this.”

The summit of Mt. Washington boasts a complex of buildings consisting of a weather station, a TV transmission building, a former barracks, a stage station, and the summit building, which houses a cafeteria and museum. A paved road and an antique cog railway carry more sedentary types to the top so they can take pictures at the summit and tell their friends they’ve been there.

There’s also a short flight of wooden steps that ascends to the very peak, which is marked by a sign that identifies it as the summit.

In the 19th century Mt. Washington was infamous. Today you’d better do your homework if you want to know its true nature.

I went up there and waited, teeth chattering, as the wind blew like hell, while a group of tourists took pictures by the sign, and then I went over and laid my hand on it, completing my journey, and hustled inside before pneumonia set in.

I didn’t fancy the idea of hiking back down. Fortunately, there’s a shuttle that runs from the stage stop, and I jumped at the chance for a ride to the bottom, even if it did cost $30.

A half hour later I was back in 87 degree temperatures and bright afternoon sunlight, dry, warm and happy.

I had survived my visit to the storm spirit. What I had assumed would take 90 minutes had actually taken four and a half hours. What the Internet had described as a “short, scenic, popular trail” had turned out to be an arduous ordeal to the peak of one of the world’s deadliest mountains.

The storm spirit lives atop Mt. Washington. Beware of his shifting moods, even in summer.

Here’s what I learned. Don’t trust the Internet. Just because a search result turns up number one, doesn’t necessarily mean it’s accurate. Poke around a little. See what other people are saying. If those of you reading this post would comment on it, it’d help. It might lift it a little higher in the search rankings so the next time some poor boob types in “great hiking in New Hampshire” it’ll return this assessment of Mt. Washington’s challenges.

Who knows, it may save someone’s life.

Previous stop on the odyssey: Palmerton, PA //

Next stop on the odyssey: Danvers, MA

| About the author: Malcolm Logan is a freelance writer who specializes in US travel and US history, designing one day driving tours, seeking out interesting US destinations and exploring US adventure travel. |

Image credits:

All images by Malcolm Logan, except: Mt. Washington in winter, W. Woods; Snow covered building, Frantz Ben Dale; From Mt. Washington looking north 1860, Public Domain; Snow covered rocks on Mt. Washington, Terrillja; Mt. Washington summit 1860, Public Domain; The storm spirit, Musubk

2 comments

Hi Malcolm – very good write up. I don;t know you but I am a friend of Gigi’s and her comment is what led me to reading your account. I write for Everytrail, which is for folks planning trips and this would make a great contribution and might get seen more. Unless you use a lot of SEO, Google Authorship etc, I wouldn’t count on the Google juice, even though this is very well done.

Hi Sally,

Thanks very much for the compliments. I would welcome the opportunity to contribute to Everytrail. What kind of compensation do you offer for a piece of this length? In addition to contributing spec pieces like this, I could also work on assignment. To keep this confidential, please contact me at my personal email, which is malcolm.logan@rcn.com.