In a country constituted of immigrants and the progeny of immigrants, immigration is surprisingly thorny issue in America. It is often said that Native Americans are the only real Americans. Everyone else is an immigrant. But even that’s not true. The ancestors of Native Americans arrived in North America 15,000 years ago as immigrants from Asia. Before that, the continent was uninhabited, devoid of people. If America is a melting pot, the pot was once empty, so we are all ingredients making up a complex stew.

Enough is enough. Everything is in balance. To add any more will ruin the flavor. This is not a new sentiment. It has been with us from the beginning and says more about the insecurities of those far enough removed from their immigrant ancestors to have achieved a sense of entitlement than it does about the impact of immigration on the wellbeing of the nation. If anything has been proven by the experience of the last 400 years, it’s that immigration is a net good.

A Growing Problem

We once understood that truth far more than we do today. For the first 200 years of European immigration to America, there were no restrictions at all on who could come in. It was only with the influx of Irish and German immigrants beginning in the 1820’s that controls were imposed. By later standards those controls were extraordinarily loose, more concerned with preventing death and disease among incoming immigrants than in keeping people from entering the country illegally. America was welcoming, and also humane.

But in the 1880’s immigration became a problem, not because the immigrants themselves were unwanted, but because of their growing numbers. The advent of steam powered oceangoing ships combined with the expansion of the European railroad system made it easier than ever for Europeans in the interior of the continent to emigrate. More than 9 million of them arrived during the decade, most of them at the port of New York. The system was in danger of being overwhelmed.

Back then immigrants were processed at Castle Garden a former defensive fort at the tip of Manhattan Island, but it was too small. Something needed to be done. In a remarkable demonstration of American ingenuity, the problem was solved by addressing two other challenges to New York City at the time, the subway and oysters.

Little Oyster Island

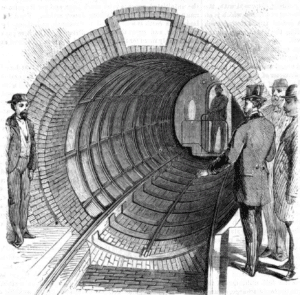

In 1888 New York City endured a blizzard that brought commerce to a halt. The experience highlighted the need for an underground railway system, a prototype of which had already been built under Broadway in Lower Manhattan. Soil and rock from the excavation lay nearby.

Meanwhile, New York Bay was a different animal than it is today. The bay was home to extensive oyster beds. Oysters were harvested enthusiastically by fishermen stationed on three islands and sold in pubs and taverns throughout the city. In those days, oysters were as associated with New York City as Wall Street and the Brooklyn Bridge.

By the 1880’s, 12 million oysters were being slurped down annually in New York. Getting rid of the shells had become a problem. Heaps of oyster shells could be seen everywhere. One giant heap gave Pearl Street its name. So when a proposal was introduced to address the growing problem by repurposing one of the bay’s three oyster islands, it was enthusiastically embraced.

The project involved expanding Little Oyster Island by building it out with the soil and rock excavated from New York’s first subway tunnel and then turning it into an immigration station. The newly built station was called Ellis Island. It opened for business on January 1st, 1892.

Two Conversations

When you take the ferry to Ellis Island from New York City today, you have the reverse experience that the immigrants did. You are inspected at the ferry terminal prior to departure (TSA screening), you are judged worthy to go, and then you are loaded onto boat and taken to Ellis Island — but not before swinging by the Statue of Liberty first.

The Statue of Liberty is one of those touchstone American experiences, like seeing Mount Rushmore or visiting the Grand Canyon. I won’t go into all the ways the Statue of Liberty no longer resonates as powerfully as it used to, but it doesn’t require much more than thirty minutes to take it in, and since the ferry stops at Liberty Island before going on to Ellis Island, you might as well stop and take a look.

Sadly, most people take the time to visit the Statue of Liberty but remain on the boat when it’s time to disembark at Ellis Island, choosing to skip that. It’s sort of like being at a cocktail party where two conversations are going on. One conversation is full of cliches and platitudes, but the other conversation is deep and meaningful with the power to change your perspective. Most people gravitate toward the former and skip the latter. I guess I’m not surprised, but I reserve the right to be disappointed.

Forty Percent of us

We had scheduled about a half hour for Ellis Island, thinking it would be a quick stop to see the Great Hall and read a few placards about the immigrant experience. We were surprised by what we found. Ellis Island is an extensive museum with state-of-the-art interactive exhibits arranged over three floors with a selection of audio tours, orientation films and docent led tours. We spent more than two hours there and still didn’t see everything the museum has to offer.

After stepping off the boat, we entered the distinctive Renaissance Revival style main building into what used to be the baggage room. Here is where arriving immigrants stacked their bags before going upstairs to be processed. You can only imagine the number of bags and trunks that used to pile up here as immigrants arrived in the thousands. At its peak, Ellis Island welcomed 5,000 immigrants a day, a total of 12 million over sixty-two years.

Those 12 million immigrants generated an extraordinary number of Americans. Today, 40% of all Americans can trace at least one relative to Ellis Island. That’s 131 million of us. Imagine how things would have been different if preventing entry had been the main purpose of the Commissioner of Immigration of the time. Surprisingly, it was just the opposite.

Questions and Examinations

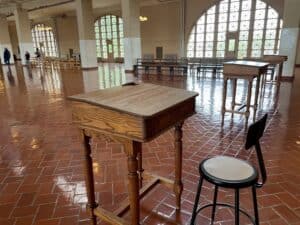

After dropping their luggage in the baggage hall, the immigrants were directed upstairs to the Great Hall, a cavernous two hundred foot long room where immigrants were screened and registered.

Twenty-nine questions awaited the anxious immigrants as they lined up at the registry desks. Most were simple: Name, age, occupation, marital status. But others seemed like traps. Who paid for your passage? How much money do you have? Do you have a trade? And the scariest question of all: What is the condition of your health? Fear ran rampant that a diagnosis of poor health would result in being sent back. America wanted workers, not invalids. Anyway, that was what they thought.

Even before they approached the registry desks, as they waited in line behind a maze of tall metal railings, the immigrants were subjected to a physical examination that included screenings for rashes, fevers, birth defects, coughs, labored breathing and “feeble mindedness”. If anything unfavorable was found, the immigrant was marked with chalk on their clothing and sent to the hospital.

Extraordinary Generosity

Three-quarters of the structures on Ellis Island constituted Ellis Island Hospital where ailing immigrants were detained and treated. Only those with the most contagious and incurable diseases were sent back. Most were housed and treated at government expense until they recovered. No belated bills followed them upon release.

And this extraordinary act of generosity didn’t end with medical treatment. Immigrant aid societies proliferated on the island, including the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), the Salvation Army, and the Daughters of the American Revolution. Detained immigrants were provided meals, money, clothing, interpreters and religious services. They were given counseling and connected with organizations on the mainland who could help them get on their feet.

What one comes away with is astonishment at the lengths our country was willing to go to welcome immigrants to America.

Due Process and Equal Treatment

The hearing room on Ellis Island. A Board of Special Inquiry considered the cases of potential troublemakers.

But not everyone was given carte blanche. Those with questionable motives were held aside for further examination. They were taken to a hearing room to have their cases heard by a Board of Special Inquiry whose main purpose was to weed out undesirables. The immigrants were allowed to make a statement and have friends an relatives speak on their behalf. If the decision went against them, they were allowed to appeal. In other words, they were given due process. Incredibly, eight of ten were admitted anyway, and breathtakingly quickly by today’s standards.

Most interestingly from our perspective the government had the immigrants’ backs. Prearranged labor contracts were illegal, meaning unscrupulous employers could not contract with foreign laborers at reduced wages for the purpose of exploiting them. Today this practice is the engine that drives illegal immigration and is often cited as the reason we cannot achieve meaningful reform. When Ellis Island was in operation, it was not permitted. Immigrants who arrived with such labor contracts were not granted entry. Employers seeking to subvert the laws of the United States by using such contracts were prosecuted. If you wanted to hire an immigrant back then, you had to treat them the same as any other American.

A Positive Experience

Immigrants dining on Ellis Island. Detained immigrants were provided meals as well as a range of helpful services.

Taken altogether, the immigrant experience at Ellis Island was a positive one, marked by a welcoming attitude largely foreign to us today. Immigrants were viewed as an important source of labor to support the nation’s growing prosperity. Which is not to say there weren’t naysayers. Then as now there were those who opposed immigration, believing that foreigners were stealing our jobs, perverting our culture and diluting our heritage. Yet the prevailing attitude was one of openness and generosity as inscribed on the Statue of Liberty: Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free …

The most amazing thing about Ellis Island is how many immigrants it managed to bring in, and how few were turned back. 98% of those seeking entry were admitted. Only 2% were sent back. Clearly, our attitude toward immigration has changed. But has it changed for the better?

The Value of Immigration

The simplistic argument opposing immigration has is that immigrants are stealing our jobs and burdening our social welfare system. While there may be some truth to that, unskilled immigrants have always provided an important function for our society by taking low paying, entry level jobs that are spurned by most legacy Americans.

By getting a foothold on the lowest rung of the ladder, newly arrived immigrants take the first step in a process of upward mobility that has characterized generations of Americans and fed the engine of our economy. To restrict it leaves jobs unfilled, inhibits growth and leaves future generations dangerously vulnerable.

At present we are in a period of population decline. Birth rates are falling. Yet our social safety net is based on the assumption that our population will continue to grow. If it doesn’t, we will be faced with a growing number of retired Americans who will be dependent on a diminishing number of workers to support them. Such a system is insupportable. Far from being a burden on our social welfare system, immigration is necessary to keep it going.

Getting off the Boat at Ellis Island: Examining the Question of Immigration in New York City

Our ancestors understood the fundamental contribution that immigration makes to America. A visit to Ellis Island drives the point home. The decency and humanity with which immigrants were treated, the common sense basis of immigration policies, and the neat efficiency with which the system functioned all come as a surprise to present day Americans who stop and wonder what went wrong.

If we want to improve our immigration system, the example has been set by our ancestors. All we have to do is look back. But first we have to get off the boat at Ellis Island.

Previous Stop on the Odyssey: New Brunswick, NJ

Next Stop on the Odyssey: Ledyard, CT

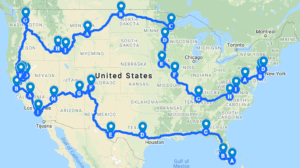

My American Odyssey Route Map

Sources

Andrews, Paul. An Immigrant’s Ellis Island Fate Depended on 29 Questions, Paul Andrews Blog Acquired 1 June 2021

Dimuro, Claudia. Mollusk Mania, Mental Floss, 10 June 2019

Ellis Island, National Park Service Acquired 1 June 2021

Ellis Island, Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation Acquired 1 June 2021

Goldman, Emma. Immigration and Deportation on Ellis Island. American Experience

Guzda, Henry P. Ellis Island a Welcome Site? Only After Years of Reform. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Acquired 1 June 2021

United States Immigration Statistics, Wikipedia Acquired 1 June 2021

Image credits

Women waiting to deboard at Ellis Island in the 1890’s, Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration

Lining up to take the ferry, Malcolm Logan

Castle Garden, Castle Clinton National Monument

Immigrants waiting to enter the US, Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration

New York’s first subway system, Public domain

Oyster market in Manhattan 1903, Freshwater and Marine Image Bank / Public domain

Statue of Liberty, Malcolm Logan

The main building at Ellis Island, Malcolm Logan

Video of immigrants arriving on Ellis Island 1892-1922, Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration

The Great Hall of Ellis Island, Malcolm Logan

Registry desks at Ellis Island, Malcolm Logan

The hospital at Ellis Island, Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration

The hearing room on Ellis Island, Malcolm Logan

Immigrants dining on Ellis Island, Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration

The dining room at Ellis Island today, Malcolm Logan

Statue of Liberty as seen from the Great Hall on Ellis Island, Malcolm Logan